The most famous editorial cartoon in Canadian history is pretty basic. It was printed in the Montreal Gazette in the fall of 1976 and depicts the two leaders of Quebec politics of the time, Liberal leader Robert Bourassa and Parti Quebecois leader René Lévesque, the latter of whom had just been elected the country’s first separatist premier.

“Okay everyone, take a Valium,” says the Lévesque caricature, stubby finger pointing at the reader.

The cartoonist was Terry Mosher, who uses the name of his daughter Aislin as his preferred nom-de-plume. “Everybody take a Valium” became an instant meme of Canadian politics in the 1970s and helped cement the 34-year-old Mosher’s rising reputation as one of the great chroniclers of the Canadian story. As the decades went on, and he stayed at the Gazette, Aislin slowly became one of those guys a certain sort of person in the eastern provinces would effortlessly dub a national treasure.

Good old Aislin, they’d say, right up there with Pierre Berton and Peter Gzowski. They showered him with awards and prizes, including a spot in the Canadian News Hall of Fame and an Order of Canada in 2002. They made a documentary about him that won a Gemini. His 47th book came out recently.

The career of Terry Mosher is a wonderful case study of how far mediocracy can take you in Canada. Strip away all of Aislin awards, praise, and reputation, and you’re confronted with an inescapable reality: his cartoons aren’t very good.

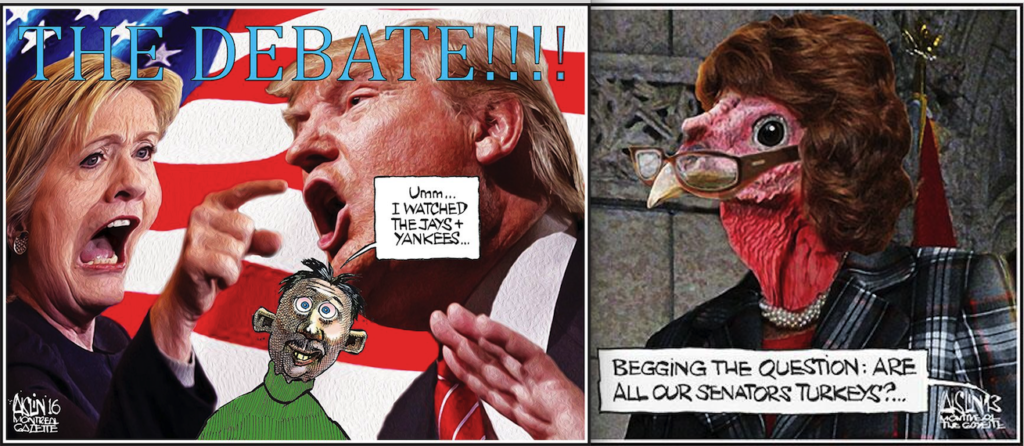

Nearly 40 years after the Valium cartoon, the 73-year-old Mosher is still at the Montreal Gazette. To say he is still “drawing,” however, would be charitable, given these days his cartoons often consist of little more than a jumbled assortment of Google image search results with some crude text slapped on top (possibly in MS Paint).

But don’t take my word for it. Feast your eyeballs on some recent Aislin classics:

Editorial cartoons don’t always have to be funny, but, as one of my friends put it, Aislin’s comics always contain a joke: “this got published.”

When I was a kid, I was fascinated by Canadian editorial cartoons and spent hours at the library poring through old collections. I was impressed by some of Mosher’s work in the 1970s, not for the humor, which was often uninspired and obtuse, but his beautifully grotesque caricatures and the elaborate fountain pen cross-hatching in which they were rendered.

But as I gradually waded my way through his collections, which he seemed to churn out at a rate of at least once a year, it became obvious that as he aged his talents were either starting to fade or he was just getting lazy. His drawings became cruder and sloppier, and eventually hand-drawn art was rarely seen at all. His commentary drifted away from offering any pretense of political insight, and instead descended into sub-Andy Rooney hot takes on the weather, sports, and (of course) These Damn Kids. Today Mosher is, by any objective standard, producing some real garbage, but insulated by endless nostalgia and praise, he seems to suffer no professional consequence for it.

I’ll cheerfully confess to sour grapes. I tried for many years to make a go at being an editorial cartoonist myself, only to find that there is virtually no market demand for what is now, increasingly, regarded as a dead art. Newspapers are hemorrhaging cash and have zero interest investing in something no one cares about. Cartoonists are being fired, not hired.

But it’s important to realize the ignoble death of Canadian editorial cartooning was not natural or inevitable. Millennials tend to regard editorial cartoons as stiff, unfunny, and clichéd, and they’re usually correct in doing so. For decades, a Canadian editor’s preferred approach to editorial cartooning was to hire a single white guy and let him draw until he died, senility be damned. This was the same model used by newspaper strips, and it certainly appeased a certain segment of the boomer readership who feared change above all else, but had the simultaneous counter-effect of informing the generations beneath that Canadian newspaper cartooning was not a remotely meritocratic enterprise. Seeking competent satire, they learned to look elsewhere.

Old cartoonists like Mosher are endlessly feted with praise about their bravery and savagery, “cutting the powerful down to size with their acidic pens” and so on. It went into particularly high gear in the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo attacks. But the sad reality is that most of the editorial cartoonists employed in Canada today are neither heroic nor clever. Increasingly, they’re barely even coherent. What they are is merely one more culpable party in the decline of traditional media, whose leading players have done their best to ensure their absence will not be noticed, let alone mourned.

***