Canadian Geographic magazine has been published for 85 years by the Royal Canadian Geographic Society (RCGS), a self-described “iconic non-profit organization” founded in 1929. Through the years, the magazine has established a respected brand as a sober periodical with a mandate “to explore and celebrate Canada’s natural and human wonders.”

But according to several former employees, Canadian Geographic has, under its current publisher and governance, strayed from that mission. In a series of posts, we will examine the magazine itself, its corporate-sponsored educational products and its connections to power in Ottawa.

CANADALAND has attempted through every available means to obtain comment for this piece from the RCGS and from Canadian Geographic Publisher André Préfontaine. Our phone messages and emails have gone unanswered.

UPDATE: Préfontaine is Canadian Geographic’s Chief Development Officer, no longer serving as publisher.

“I asked that my name be taken off the masthead, and soon after, I resigned,” says Alan Morantz, former senior editor of Canadian Geographic magazine.

Morantz, who worked on contract at the magazine for over three years, says that management abandoned the editorial policy of identifying sponsored content with an article in its December 2012 issue about polar research.

The research being featured was an initiative of the Weston Foundation, who also sponsored the article, according to Morantz.

“Previously we would have labeled a feature like this ‘Special Section, in partnership with the Weston Foundation,'” he recalls. “But the disclaimer was changed right before publication to ‘Special Report on Northern Research.’ You don’t take money from a source,” he tells CANADALAND, “and pass off the resulting work as journalism.”

The archived version of the article on Canadian Geographic’s website contains no disclaimer at all.

***

Author and magazine journalist Curtis Gillespie says he had a similar experience, after which, he tells CANADALAND, “I vowed never to have anything to do with Canadian Geographic ever again, as long as [publisher] André Préfontaine was part of it.”

At first, Gillespie had a good relationship with the magazine. He had written a feature on the oil sands for their June 2008 issue that was highly critical of the environmental impact of the industry. When he was asked to write a long feature on the Calgary Stampede two years later, he was eager to accept.

“What I didn’t know,” says Gillespie, “was that in the interim, their business model had changed.”

Gillespie says his editor disclosed to him that the article he was being commissioned to write, and the entire issue it would appear in, were being sponsored by its subject, the Calgary Stampede. Kurt Kadatz, a spokesperson for the Calgary Stampede, confirms to CANADALAND that the Stampede entered into a partnership with Canadian Geographic in 2012 that included “content in Cdn Geo.”

Gillespie says he expressed concern about the arrangement, but was promised editorial independence.

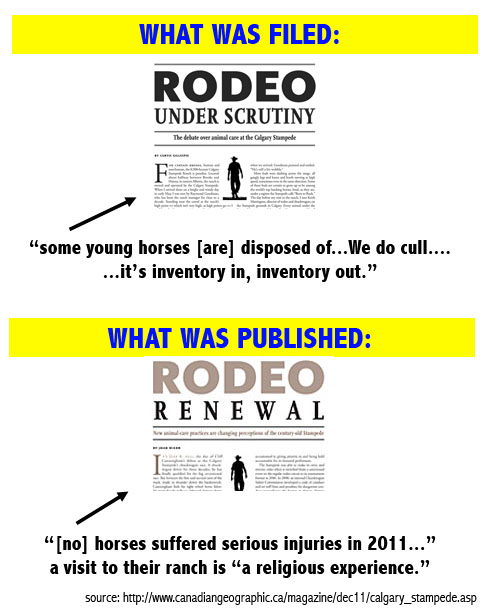

He visited the Calgary Stampede Ranch, spoke to a livestock handler, a veterinarian, academics, and activists, and delivered a thoughtful piece that was generally sympathetic to the Stampede. He did however learn that the Stampede bred horses specifically to be used as bucking broncos. These horses were regularly culled; those that didn’t buck wildly enough were “disposed of.” Gillespie included the detail in his piece, “Rodeo under Scrutiny.”

At first, Canadian Geographic’s response was ecstatic.

In emails provided to CANADALAND, Gillespie’s editor called the piece “brilliant,” a “magnum opus”. The piece was edited, laid-out and illustrated with vivid photos, and was set for publication.

But then things changed. Gillespie’s editor wrote back to sheepishly say that Canadian Geographic’s publisher, André Préfontaine, had pulled the story, because he felt it was unfair to the Stampede.

The magazine instead ran a piece on animal welfare at the Stampede by a writer who had actually once been hired by the Stampede to write an official history of the rodeo.

The piece appears here on the Canadian Geographic website, where it is not identified in any way as sponsored content.

“To me, the magazine was essentially lying to its readers,” Curtis Gillespie says. “I was left mortified for them, journalistically.”

***

“That was one of the primary reasons why I left,” says former Canadian Geographic cartographer Steven Fick, when asked by CANADALAND about sponsor influence on editorial content. He had created a map illustrating the impact distribution of airborne pollution from oil sands refinery stacks on Alberta’s lakes. It was pulled from an issue about the water table shed, because, says Fick, Canadian Geographic was in the midst of sponsorship negotiations with Shell Canada.

After some internal debate between Fick’s editor and publisher Préfontaine (and after negotiations with Shell concluded), the map was published in Canadian Geographic’s July/August 2011 issue.

It was too little, too late for Steven Fick, who parted ways with the magazine.

***

In December 2012, Canadian Geographic’s acting editor Dan Rubinstein left the magazine’s top job, saying his plan was to write.

This past spring his book Born to Walk was published by ECW Press. From his prologue:

“…(I spent) a decade as a magazine editor, cresting at the top post at a respected publication. Financial turmoil threatened to swamp the magazine industry. The non-profit where I worked responded by creating ‘independent and objective’ content in partnership with corporate and government backers…Our sponsors were determined to ramp up either public support or profits, and I was aiding and abetting their newspeak.

My dream job, which I had moved across the country to take, became a nightmare… A watchdog was opening the gate for the wolves.”

***

Canadian Geographic’s sponsors have, according to our sources, enjoyed a unique level of control over the magazine’s editorial content. But their influence does not end there. Next, we will look at the impact that these corporate sponsors have had on the school curriculum the RCGS produces and distributes for free to a network of over 13,000 classroom teachers throughout Canada.

NEXT: The oil sands, for kids.