Vanshika Dhawan is a writer and law student based in Toronto. You can find her on Twitter @vdhwn.

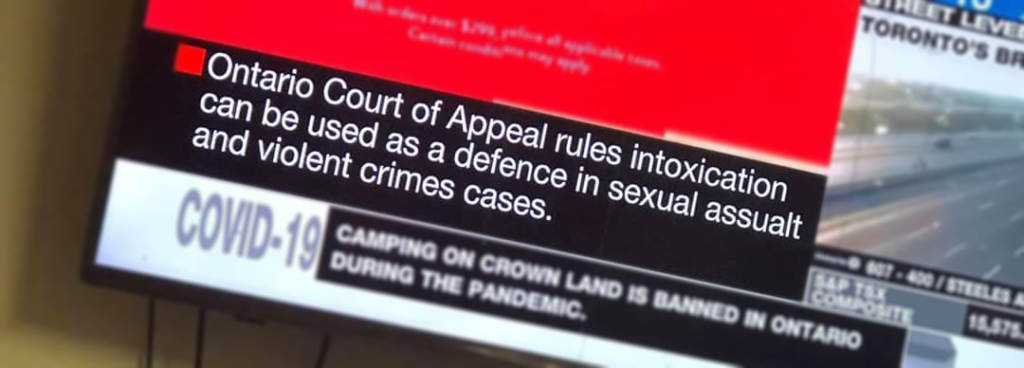

Earlier this month, the Ontario Court of Appeal (ONCA) released a unanimous 110-page decision for the companion cases of R v Sullivan and R v Chan. Perhaps you saw the tweets linking to various articles on the decision, with headlines like, “Ontario court throws out law barring self-induced intoxication as defence for sexual assault.” Maybe you caught the chyron on CP24 that read, “Ontario Court of Appeal rules intoxication can be used as a defence in sexual assault and violent crimes cases,” or MPP Jill Andrew’s tweet that shared a photo of it. If you were enraged by the far-reaching implications for sexual assault survivors, you may have been one of the nearly 300,000 people who signed this statement calling for an appeal, or one of the many others who signed this petition, or this one.

But the headlines and petitions got it so egregiously wrong that it harmed survivors of sexual assault in the process. Those that mentioned sexual assault capitalized on and exploited the pain and trauma that survivors of sexual assault experience at the hands of our criminal justice system.

Hopefully, you also read the explanations by lawyers (including the defence lawyer for Sullivan) and law students, who took to social media to try to correct the record. Briefly, the ONCA decision deemed section 33.1 of the Criminal Code — which stated that the defence of extreme intoxication was not available in cases where the accused interfered with the bodily integrity of another person — unconstitutional. This provision was enacted in 1995, in response to public outcry after a 1994 Supreme Court of Canada sexual assault case, R v Daviault, that essentially said that extreme intoxication to the point of automatism was a valid defence. The reasoning was that if one gets so intoxicated they are not in control of their actions, they cannot form the intent required to convict them of a crime — a very high bar.

The media misled the public by conflating “intoxication” and “extreme intoxication to the point of automatism.” CP24’s chyron was particularly dangerous, given that CP24 used the term “intoxication” only and viewers could not immediately engage with an article that explained the nuance of the decision. Even media outlets like The Globe and Mail that did use the term “extreme intoxication” left room for interpretation. The colloquial understanding of “extreme intoxication” is “blackout drunk.” Being “blackout drunk” is not the same as “extreme intoxication to the point of automatism.” Reasonable interpretations of these headlines led to the patently incorrect and incredibly harmful conclusion that defendants in future cases could be acquitted of sexual assault because they were drunk.

This decision undeniably has implications for survivors of sexual assault, as organizations such as the Women’s Legal Action and Education Fund have outlined. But any headlines that discussed intoxication and sexual assault were reckless. Headlines matter. They change the way we think. It often seems like people share articles based on the headline alone, especially on Twitter. And misinformation spreads a lot faster than information does, especially when it has an air of plausibility to it.

These headlines were believable precisely because of survivors’ trauma: not only the trauma from their assaults, but the trauma experienced at the hands of the police who dismiss their experiences, the prosecutors who assess their cases based on the likelihood of conviction, and the defence lawyers who discredit them. Of all indictable offences, sexual assault cases are the least likely to see a conviction after being reported to the police.

At every stage of the reporting process, survivors are forced to retell and relive their assault in order to seek retributive justice, which is often denied. The public took these headlines at face value, was outraged, and directed its anger at the idea that mere intoxication could be a defence for sexual assault, an idea that is not true and that the court never endorsed.

It is crucially important for the media and for politicians to get these things right the first time, especially considering the way misinformation spreads on social media. Sullivan/Chan were not sexual assault cases. Neither Chan nor Sullivan intended to become as intoxicated as they did. Chan had a severe reaction to “magic mushrooms”; Sullivan attempted suicide by overdosing on prescription antidepressants. Both men attacked and stabbed loved ones in unforeseeable drug-induced psychoses. Neither case involved alcohol consumption. Moreover, expert evidence since Daviault suggests that the state of automatism is virtually impossible to achieve with alcohol alone. The ONCA acknowledges this in their decision, going so far as to say that “had similar evidence been presented and accepted at Mr. Daviault’s retrial, he would have been convicted.”

Misreporting undermines faith in the justice system. We must criticize the legal system when decisions perpetuate rape myths and dismiss the experiences of survivors. But the discourse generated by the reporting on this ruling is also incredibly harmful to survivors, like this article’s headline that calls women’s groups’ anger at this decision “overblown.” Although it is true that the defence would be extremely difficult to successfully raise in a sexual assault case, survivors’ concerns are still legitimate. Calling it overblown is dismissive of survivors’ lived experiences. As women’s rights advocate Julie Lalonde correctly points out, it is fundamentally wrong to ask survivors of sexual assault to put their faith in a legal system that has never prioritized nor served to protect them.

Even if the chances of this defence succeeding in a sexual assault case are minuscule, the pain survivors feel is valid and exists — independent of the misreporting. Both news outlets and the legal community must strive to explain these cases in a way that is accessible and empathetic to the plight of survivors.

I am inclined to believe that misleading headlines were not deliberate, but rather a vast oversimplification of a very complicated area of the law. But anyone who spreads misinformation has a responsibility to correct it — especially major news outlets and politicians in whom the public has placed their trust.

Regardless of intent, it is manipulative and exploitative to misrepresent and mobilize around the most provocative part of a ruling without necessarily framing it in the proper legal context. Survivors of sexual assault were unnecessarily triggered and retraumatized by the reporting around this case. This harm was both immeasurable and avoidable, had there been better training, legal literacy, and editorial oversight.

Some public petitions went beyond misrepresenting the meaning of the “intoxication defence,” displaying a fundamental misunderstanding of our civic and justice systems. For example, this one, which garnered over 50,000 signatures, suggested that the ONCA decision was “in violation of the Criminal Code of Canada, section 33.1,” when it is actually the courts’ jurisdiction to rule on whether s. 33.1 violates the Charter, a check and balance that is built into our democratic system. Judicial review in these cases is often referred to as “dialogue” between the courts and the legislature. Just as we trust our elected officials to legislate for our benefit, it is imperative that we trust the courts to independently determine when legislation violates the Constitution and Charter— especially when legislation is drafted in a way that protects certain groups at the direct expense of others. This is democracy in action.

I am disappointed — in the way the media crafted these headlines, in the way politicians doubled down on their stances rather than correcting the record, and in the way harmful, divisive discourse spread on social media like wildfire. The Crown is seeking leave to appeal. If leave is granted, then the Supreme Court will hear arguments both for and against upholding the ONCA decision that deems s. 33.1 unconstitutional.

I can only hope we learn from our mistakes and engage more responsibly and critically with the Supreme Court decision, if/when we get one. The ultimate outcome may be the same, and if so, it will be up to the federal government to redraft legislation that is both constitutional and achieves the objective of protecting vulnerable groups from intoxication-related gender-based violence, without punishing people in tragic circumstances unrelated to gender-based violence like Sullivan and Chan.

This is first and foremost an access-to-justice issue. The law is complicated and legal jargon is inaccessible, and the response to these cases only further highlights the need to address these rulings for the public interest. Making the implications of decisions like these accessible and understandable needs to be a priority for many reasons, especially so survivors can make informed decisions about reporting instances of sexual assault and seeking justice.