Back in the spring, Vox Pop Labs — a public opinion research company best known for its Vote Compass and widely derided MyDemocracy.ca surveys — was supposed to launch a Canada 150 “signature project” called Project Tessera with the CBC. In June, Vox Pop’s CEO told media the survey was being redesigned and would be released some time in the fall. Two weeks ago, a CBC representative told CANADALAND that the project, which the Trudeau government had funded with a $576,500 grant, would be online this past Monday.

It is still nowhere to be found.

“Our plan is to launch on November 27th, and we are not contributing any money,” CBC spokesperson Chuck Thompson said in an email on November 17. “With respect to delays, CBC and Vox Pop have been working together to ensure the best launch possible for this important initiative.”

“The project will launch next week,” said Vox Pop Labs founder and CEO Clifton van der Linden on November 19. “Watch for it on CBC and Radio-Canada.”

According to application documents submitted to Canadian Heritage (embedded at the end of this article) that I obtained through an access-to-information request and first reported on my Raving Canuck blog in December 2016, the development of the project began in the middle of 2016 and was to be launched in “early 2017.” I filed the request — in an early fishing expedition for Canada 150 grant applications — a few months before Vox Pop’s MyDemocracy.ca survey was ridiculed by critics for leading questions that seemed to prod respondents towards the Liberals’ preferred electoral reforms and for the goofy personality classifications (e.g., “Guardians,” “Challengers”) it assigned to respondents at the end. Both The Globe and Mail and National Post published satirical surveys mocking it.

In the Canadian Heritage assessment of the Project Tessera application, the program officer wrote, “Given the track record and experience of the applicant, it is expected that the project will be created and launched in a timely fashion, resulting in a significant impact during the celebratory period in 2017.”

Maclean’s did their own report on Project Tessera in June, on how it had been postponed until some time in the fall. They noted the Project Tessera website had been taken down shortly after the magazine’s reporter contacted Vox Pop Labs, and that the email address provided on the website was also dead. At the time, the Twitter account had only 21 followers and eight published tweets; it now only has 20 followers and has remained inactive since November 2016. CEO van der Linden told Maclean’s that after doing panel studies, both large and small, “We modified our approach to the user experience, opting for a more nuanced model than the classification model that we originally proposed. The modified project scope and specifications will take additional time for us to implement.” He also said it was better not to launch Project Tessera at the same time as other Canada 150 projects, so they wouldn’t be “lost in the shuffle,” adding, “I realize that this may come off as a post-hoc justification, but I genuinely believe that this is in the best interests of the initiative.”

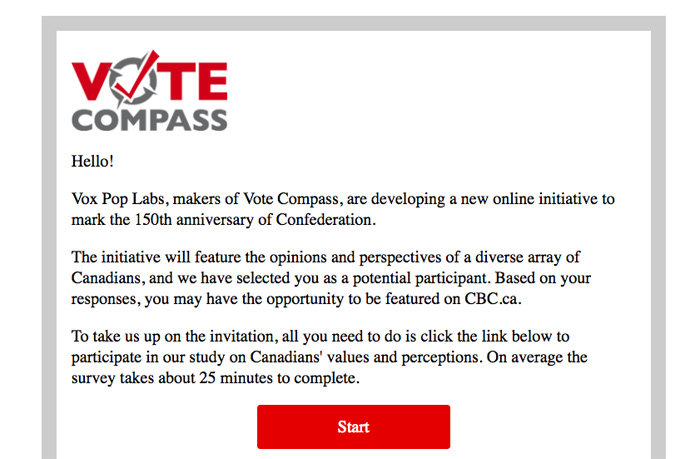

At the time I was beginning research on this story, CANADALAND news editor Jonathan Goldsbie received an email invitation from “The Vote Compass Team” to fill out a survey on November 20 to “help shape” a “new online initiative to mark the 150th anniversary of Confederation.”

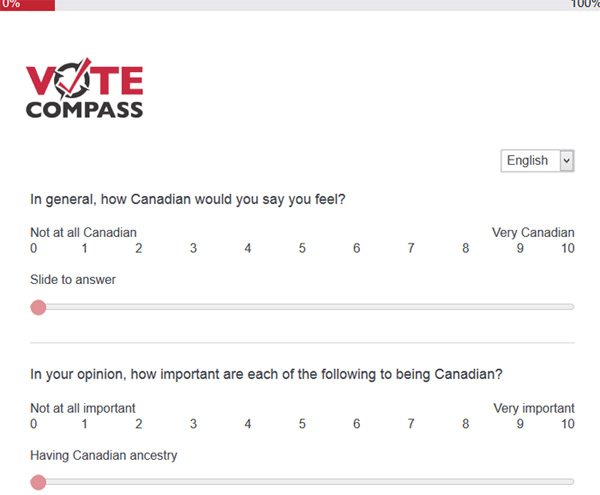

It’s unclear whether or not this survey was the final Project Tessera survey meant to be unveiled last Monday; van der Linden did not respond to a follow-up question asking about it. However, this survey wasn’t called Project Tessera and didn’t classify respondents into categories or archetypes like MyDemocracy.ca did. The application had said it would.

“Tessera” means an individual piece in a mosaic, and Vox Pop Labs chose the name for the survey because, “More than a simple association of user to archetype … each user will be presented with a personalized analysis which simultaneously celebrates their individual identity and inclusion in the broader Canadian collective.” The tool was also, according to the grant documents, supposed to survey users on “themes such as culture, values, symbols, belonging, etc.” The demo quiz filled out by CANADALAND doesn’t give any classifications and doesn’t seem to cover all of the themes.

$5.6 million for an ice rink at Parliament Hill, steps from the world’s largest natural skating rink, the Rideau Canal. $555,000 for Canada 150 plastic wrap covering a Canada Post building. $1.3 million to St. Joseph Media to create a website and app called “Passport 2017.” The list of questionable spending of the half a billion dollars for Canada 150 is a long one, but does Project Tessera deserve to be on it?

Vox Pop Labs received $250,000 more for Project Tessera than it did for MyDemocracy.ca (which had been a $326,570 contract) and said it was “committed to operating Project Tessera exclusively on a cost recovery basis.”

Van der Linden explained, in an email interview late last year, why this new project would have a much more expensive price tag.

“Project Tessera is a much larger undertaking than MyDemocracy.ca. It involves national focus groups, a respondent panel five times the size of that used for MyDemocracy.ca, a working conference bringing together leading scholars in the field, and a more complex design and technical architecture.”

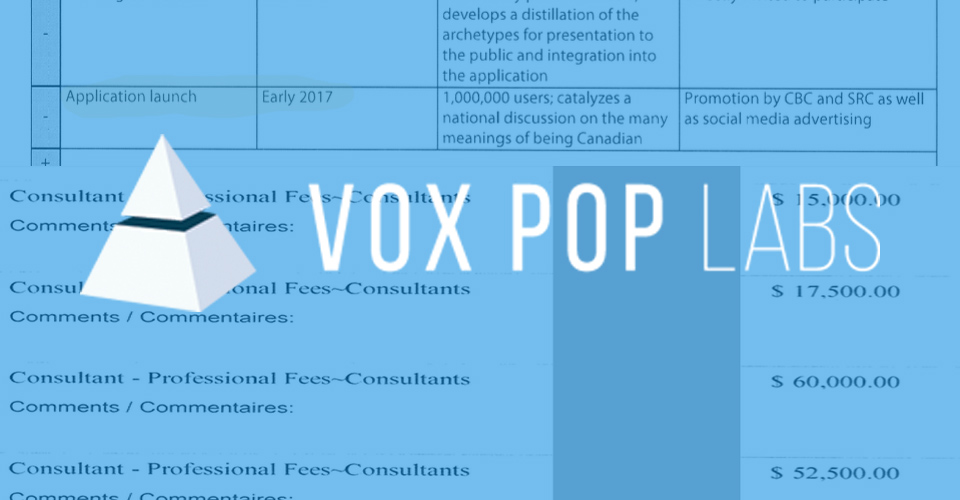

Vox Pop’s Canada 150 grant is broken down into $300,500 for consultant fees, $175,000 for outreach, $63,000 for a workshop or seminar, $24,000 in equipment costs, and $14,000 in venue costs. One of the expenses was a two-day conference in Montreal, including hotel rooms, food, hotels, and flights for around 30 academics in order to “hone” the Project Tessera tool.

“‘Consulting time’ is usually the least expensive item on a public opinion project. Whoever approved this did not understand the process,” says Mario Canseco, pollster at Vancouver-based Insights West.

“We sometimes have clients that require a lot of information that can only be gathered with a survey that takes 15-20 minutes. In these occasions, the monetary incentive that is offered to a participant (as a ‘thank you’ for their time) can be as high as $10. This is advertised as a 25-minute survey (extremely long for industry standards) where the only incentive offered is, maybe, appearing on the CBC,” he says in an email, adding that respondents usually lose interest in a survey after 12 minutes.

Another source, familiar with the typical costing of polls (and who requested anonymity due to the nature of his work), says in an email that “a poll on this topic (identity and values) might typically entail a budget of somewhere between $50,000 to $200,000. But frankly, I haven’t seen any polls on this topic for anything near that price in at least 10 years. This seems to be an unusually extravagant budget for a polling topic that no one really seems that interested in these days.”

CBC and van der Linden beg to differ. In the application to Canadian Heritage, Vox Pop Labs said Project Tessera “has the potential to generate an unparalleled dataset on public perceptions about Canada and what it means to be Canadian.”

Canseco believes it would be disingenuous if CBC and Vox Pop Labs ended up characterizing this survey as an accurate reflection of what the general population thinks and believes, because the sample, no matter how large, would be from a subset of the Canadian population accessing the CBC website.

“This is the problem. When there is no care to select the sample properly and reflect the population, it is [statistically] meaningless,” he says. “But unprepared journalists will say ‘Oh, a sample of 20,000! It has to be better than a poll of 1,000.’ SurveyMonkey had a 70,000-respondent poll before the U.S. election and had Trump low. We spoke with about 1,000 and called it right. Sample size does not matter.”

Both Vox Pop Labs — whose other big clients have included the Toronto Star and the government of New Zealand — and the CBC like to boast about the wild popularity of their quizzes.

“Vote Compass has been used by more than 3 million Canadians across 10 federal and provincial elections since 2011,” states a Vox Pop representative in the grant application form.

“There were more than 1,800,000 interactions with Vote Compass – La Boussole électorale during the last federal election,” wrote CBC’s director of journalistic and public accountability and engagement Jack Nagler in a letter of recommendation to Canadian Heritage.

Back when Vote Compass was launched in 2011, a Queen’s professor of policy and political studies noticed that the compass appeared to unintentionally default toward the Liberals as a political median.

Van der Linden said last year that such accusations of bias “have been entirely debunked, both in the public discourse and academic studies.”

Thompson and Nagler did not respond to follow-up questions about whether the CBC was concerned about Vox Pop’s surveys, following the allegations that the 2011 Vote Compass was skewed.

Canadians can make up their own minds on the utility and value of Vox Pop Labs’ Canada 150 survey when the long-delayed Project Tessera finally gets released sometime soon — hopefully.

“The project is progressing well and will be launched shortly,” said Canadian Heritage spokesperson David Larose in an email on November 21. “Please stay tuned for an announcement in the near future.”