Bruce Monk was an instructor at the Royal Winnipeg Ballet for over twenty years. He is also, according to several of his former students, a predator who coerced vulnerable girls into posing for explicit photographs.

What’s more, Monk has been accused of selling these photographs online and several of the nudes he took are currently available on eBay for purchase. A police investigation is ongoing.

Most of the women who have made accusations of abuse against Monk remain anonymous. Many of them still have connections to the ballet world and are worried about both professional and personal repercussions.

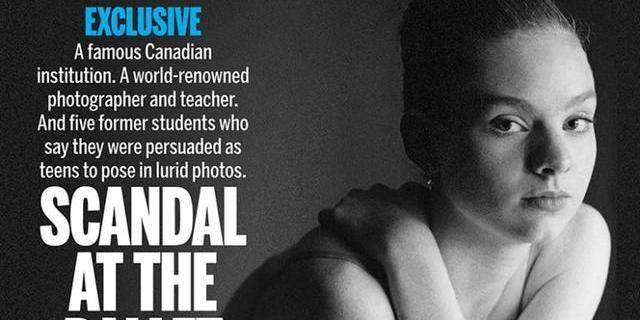

But Serena McCarroll and others spoke out on the record as part of a Macleans cover story in April by Nicholas Köhler. McCarroll hoped that going public would give the accusations a greater resonance than some might think is lacking with anonymous allegations.

Unfortunately, in its treatment of the story, Macleans side-stepped fundamental issues at play and portrayed its on the record victim in an unclear light, to the point where it has left her frustrated and saddened by the piece.

Here’s how an early anecdote is framed by Köhler on McCarroll, his subject:

“The enclosed negatives featured McCarroll as a girl of 16 or 17, her cheeks still pudgy. Minutes after Monk took the exposures, McCarroll says, the top of her bodysuit came down.”

Readers are left with an image of a young girl exposed to someone who is, obstensibly, her abuser. She offered this story to Macleans in order to bring about information that is valuable to the public interest, hoping it would be treated with sensitivity and respect. But, to her shock, McCarroll wasn’t exposed in the way magazine readers are originally led to believe. Reached for comment, she notes:

“It’s very difficult to read the artful retelling of an event that was so disturbing to me. Early in the article Nicholas tells the reader that the top of my bodysuit came down minutes after Bruce took the headshots of me shown in the magazine. He takes 29 paragraphs to clarify that my arms were across my chest the entire time; that I was fully covering myself. Why do that? Why take so long? My guess is because a topless teenage girl is tantalizing whereas a girl trying to cover herself isn’t. But why make something like this titillating?”

This is a problem when the tendency to embellish in narrative journalism interferes with the clarity necessary for a sensitive story. For nothing more than dramatic flourish, Macleans leaves one of Monk’s victims exposed through a questionable portrayal of what happened to her.

The narrative and artistic treatment of her abuse is laid out alongside praise for the artistic merits of Monk’s photographry. From Macleans‘ story:

With his camera, he slipped in and out of classes, or backstage during costume changes, documenting the flow of life—able, in the words of a Winnipeg Free Press profile five years ago, “to glide unnoticed through the wings during performances and capture images that probably no outsider could.” As Monk, now in his early 60s, put it: “I’m kind of invisible, because I’m there all the time . . . You stop being observed and just become the observer.”

That unique perspective is in evidence in the ethereal From the Gantry, a photograph taken from high above the stage and featuring two ballerinas from the waist down, the rest of their bodies cast in shadow below.

Once again: this is a man who made underage girls pose against their will. Viewed with the context of what we know about his work, about his practice and about his abuse of women what exactly is ethereal about Monk’s photography?

The sensationalist treatment of what happened to McCarroll and of Monk’s work is in line with what Macleans generically bills as a “Scandal at the Ballet” (the title of the article), which grossly minimizes what Bruce Monk did to his students. McCarroll, of the story’s presentation, adds:

The cover headline “Scandal at the Ballet” does not point to the severity of what’s inside: a story about years of unchecked abuse by a figure of authority in a respected Canadian institution, a story about the manipulation of children. The fear I felt in that room with him never left me.”

We need to be very clear about one thing: this is not a scandal.

A married person having an affair with another consenting adult is a scandal.

A financial officer who siphons funds from a charitable organization is a scandal.

A celebrity caught shoplifting is a scandal.

A man who carefully selects, grooms and then abuses girls is not a scandal. It’s a violation.

When we talk about what Monk is alleged to have done, we have to be very careful to talk about in terms of what it really is – a form of sexual violence that was perpetrated against vulnerable young women.

McCarroll’s account of what Monk did to her is chilling, and because of the way it was portrayed by Macleans, she deserves the opportunity to have it presented with greater detail. I’ve asked her to recount her involvement with Bruce Monk, and here is the story including details that were not in the magazine piece.

McCarroll says that she was sought out by Monk after she’d been asked to leave the Winnipeg Ballet School due to an injury. He offered to help her out by taking professional head shots for her at a friendly cost.

McCarroll says she was immediately uneasy; according to her, there were rumours circulating for years about Monk’s inappropriate relationships with his students, and that one who housesat for him found explicit photographs of another student who had recently left the school.

But while Monk had a reputation as something of a creep with some of the girls he trained, McCarrol says he was also the only teacher to offer her any sympathy after she was dismissed. She knew that if she wanted to continue a career in ballet, she would need professional photographs of herself.

McCarroll says she figured it made sense to get her portraits done while she was still in top shape, before she would take time off from dancing to heal from her injury. She says she ultimately decided to take Monk up on his offer, figuring that if she brought an adult guardian he wouldn’t try anything untowards.

Unfortunately, according to McCarroll’s account, Monk anticipated something like this. When McCarroll and her guardian arrived at his apartment, she says they were quickly separated, with the chaperone being ushered over to a corner of the room that did not have a view of the area where the photo shoot was going to take place.

McCarroll says that Monk took a few pictures and then asked her to slide the straps of her bodysuit down her arms, saying that they were ruining the line of her neck. She details his having her lower the straps further and further until the upper part of her bodysuit hung around her waist. McCarroll says she was uncomfortable about the direction the shoot was taking but not sure what to say or do, and so she kept her arms crossed over her chest.

According to McCarroll, Monk told her to drop her arms and she refused. She says he asked again. And again. She says he said it over and over, his voice as calm as if he was asking her to tilt her head or smile. McCarroll says this went on until her chaperone sensed that something was wrong and came over to investigate. Her guardian was shocked to find the sixteen year old half naked, says McCarroll, who recounts her arms still wrapped around her upper body.

Later, McCarroll says that Monk told her that he wanted to take more pictures of her. He asked her to come back alone, on a day when his partner wasn’t home. Monk told her that he liked doing “body studies” of his subjects, something he said his partner didn’t really understand.

For his part, Monk has said, in regards to all the stories published about him, “I have no comment on any of these ridiculous allegations.”

Other former Royal Winnipeg Ballet School students who have come forward have stories similar to McCarroll’s. Each describes feeling completely powerless both during and after their respective enounters with Monk.

Sarah Doucet, for example, remembers quite clearly not wanting to remove her clothing. But, as she told Macleans, “I didn’t feel like I had any choice in the matter.”

Another woman photographed by Monk, who prefers to remain anonymous, says that while she felt deeply uncomfortable about stripping down to nothing but her shorts, she did so because she “definitely wanted to please him.”

Alena Rieger, who did a photo shoot with Monk in 2013 shortly after she turned 18, told Macleans: “Eventually, I was completely nude. I didn’t know how I got there. It didn’t feel like there was any point for me to say no.”

This is what is important for people to recognize: that the girls who were instructed by Monk to remove their clothing felt like they didn’t have any choice in the matter. They didn’t feel like there was any point in saying no. They were completely conditioned to want to please him no matter what their own feelings.

While it’s true that women in general are socialized to treat men’s desires this way, it’s also worth nothing that places like the Royal Winnipeg Ballet School basically teach this disturbing dynamic as part of their curriculum.

McCarroll tells me, “[Monk] was aided by the fact that ballet schools are generally abusive and insular environments. They are run like military academies. Fear and degradation are the primary teaching tactics. Every girl knows that she is dispensable.”

Or, as Suzanne Gordon put it in her book Off Balance: The Real World of Ballet, “Ballet companies are rigid hierarchies … [their] social structure is borrowed from monarchy. The relationship between the student and the teacher, or between the professional dancer and the company director, involves the same stylized deference, the same obedient attentiveness, that a courtier showed a monarch.”

All of this aligns with a greater complication in the arts and in social institutions in general. How on earth is it possible that we not only allow these types of misogynistic environments to exist, but celebrate them as temples for the highest forms of art?

It is not at all surprising that someone like Monk existed in the ballet world. What’s surprising is that there aren’t more stories like this – although the consequences for speaking out, including the treatment of female victims in the media, are certainly a factor here.

The price of speaking out against abusers like Monk is steep; as a highly-placed man in the ballet world, he had the ability to end careers before they’d even begun. On top of that, the women he targetted knew that if they told their stories, they would face disbelief or even accusations of having been complicit in what he’d done. This is what happened when the allegations against Jian Ghomeshi first became known. The tide of public opinion didn’t change until Lucy DeCoutere went on record, and even then there were people who blamed Ghomeshi’s victims.

Monk’s victims allege that his abuse went on for over two decades, and it is impossible that the Royal Winnipeg Ballet School was completely ignorant of the fact that something was going on.

Not only did many of his alleged abuses take place on school property, either in an office or a studio or the building’s boiler room, but after Monk photographed Alena Rieger, her then-boyfriend sent the school an email detailing what had happened. The administration had every reason to know what Monk was doing, but instead turned a blind eye. It became a twisted version of “don’t ask, don’t tell,” the sort of environment in which abusive situations thrive.

Winnipeg police launched an investigation into Bruce Monk in 2012. When they first applied for a search warrant, their request was denied because the magistrate involved felt that because that the alleged offences had happened so long ago that there was little chance of any evidence remaining.

Not long after this, McCarroll wrote to Monk asking him to send her any photographs he still had of her. He replied with an envelope full of negatives and a note saying,“I have sent you all existing photographic materials. I did destroy all but these negatives years ago and these are truly the only materials that exist[.] I sincerely regret the problem I have caused you[.]”

McCarroll felt certain that he was lying about the existence of other negatives because in all of the images he sent her, the straps of her bodysuit were firmly on her shoulders.

After submitting this new evidence to the magistrate, the police were granted the search warrant and raided Monk’s apartment. They seized tens of thousands of images.

It wasn’t until then that the Royal Winnipeg Ballet School placed Monk, now in his 60s, on paid administrative leave. After the first Macleans article was published, Monk was fired – and the magazine, for all its presentation issues, should be given credit for helping bring his termination about.

In spite of all this, the criminal case now seems to be in limbo. The allegations against Monk predate the Canadian Criminal Code’s child pornography provisions, and people can’t be charged with offences that didn’t exist when the crime was committed.

Meanwhile, Monk’s prints are available for purchase on eBay.

* * * * *

In spite of how Macleans told this story, what Bruce Monk is alleged to have done is not a scandal, nor is it something specific to the world of professional dance. This type of abuse does not happen in a vacuum – it happens in a society where survivors are regularly disbelieved, and women are frightened to speak out because of the potential consequences to themselves. It happens in a society where we all prefer to look the other way and hope the problem will resolve itself because that’s easier and more comfortable.

The type of abuse Monk is accused of inflicting is, at its core, no different from what Jian Ghomeshi did. Both preyed on vulnerable women; both used their power and influence to silence their victims. The term “rape culture” is tossed around a lot, but this is a very clear example of how our culture allows for the perpetuation of sexual abuse.

We all as a society collude on continuing these cycles of abuse. We need to own that, and we need to fix it. The first step is calling things what they really are. This is violence. This is abuse. This is rape culture.