NOTE: For purposes of clarity, in this article “WE” refers to all entities past and present in the WE network of organizations, including ME to WE, WE Charity, and Free The Children.

Craig Kielburger, the co-founder of the WE organization, got married in June 2016. One month earlier, a WE employee in Illinois named Francie Schnipke Richards received a wedding invitation via a work email from Lisa Lisle, Craig’s then-chief-of-staff. She replied that it would be “such an honour” to attend and offered her help, writing: “I don’t expect to be sitting around.”

According to WE, Schnipke Richards was one of a handful of employees who attended Craig Kielburger’s wedding both as guests and as WE volunteers, tasked with checking-in and hosting major donors and supporters, such as by “engaging in conversation with them.”

They “were not compelled to do so,” said WE.

WE is “the most exciting place in the world to make a difference,” according to its website.

The WE organization is a family of entities including WE Charity, whose international development work includes providing clean drinking water and access to education to youth, and ME to WE, a “social enterprise” business whose profits are donated to WE Charity and reinvested to “grow the mission of the social enterprise.”

“My colleagues come into work every day and care about what they’re doing. They put their whole heart and effort into making the world a better place,” said Lauren Martin, who does event planning for WE. “We do great work and help others do great work.”

But two dozen former employees, who worked with WE over the past two decades, laid out what they believed to be serious internal problems at the organization. Some suggested WE’s noble charitable mission was used to enable an internal culture of fear and secrecy that harmed its workers and at times, some said, compromised their safety and wellbeing. Some said WE demanded total personal commitment from young workers and volunteers, extracting 16-hour work days with unpaid overtime, at near-minimum wage. Some said that WE management used guilt to suppress dissent from employees, stressing that requests for better pay and support would take resources away from needy children in Africa.

“It is incredibly toxic and inappropriate, the way they treat young people.”

FORMER WE DIRECTOR

The employees who spoke to Canadaland ranged from volunteers and interns to managers and directors.

“The way they treat young people,” said a former WE director who left in the last three years, “is incredibly toxic and inappropriate.”

Fourteen former employees likened WE to a cult, describing it as “cult-ish” or “cult-like.” Six former employees, interviewed separately, offered this comparison without prompting. Canadaland then asked other former and current WE employees if they believed this was an accurate comparison. Eight agreed that it was, and five said it was not.

WE is active in over 16,000 public and private schools, where kids are recruited to join the “We Movement.” Some of our sources who went on to work for WE began in high school as WE volunteers. One former employee alleged that she was asked to use misleading messages to motivate schoolchildren in a fundraising campaign. Former employees raised concerns about WE’s use of celebrities to connect with kids, and its practice of presenting its co-founder brothers, Craig and Marc Kielburger, as celebrities in their own right. The brothers, who are promoted publicly as inspiring leaders, were said by some to be prone to angry outbursts towards staff in private.

“Marc is a bully, one hundred per cent,” said a former WE director.

WE vigorously denied these claims, admitting that they made mistakes in the past but said the organization has since learned its lessons. WE is adamant that the current reality for employees is very different from when it was a “youth-led” organization. In accounts and documentation WE provided to Canadaland, the prevailing message was that WE may have faced challenges but currently serves as a world-class exemplar of charitable innovation, youth stewardship, and corporate diligence. WE insisted that the Kielburger brothers are professional, kind, and deeply respected by their staff and peers, and that the members of their workforce, past and present, have been overwhelmingly satisfied with the organization. Four current and former WE employees with whom Canadaland spoke had entirely positive accounts.

In a statement, WE accused Canadaland of “leading the sources” to compare it to a cult, and said that “Canadaland is simply underscoring its bias and malice by attempting to incorrectly portray WE as ‘cult-like.’” They also cited a 2018 review by HR consultancy Lee Hecht Harrison Knightsbridge [pdf], which found that staff described WE as “having a strong culture with contagious energy stemming from employees’ unified passion to make a difference.”

WE has served Canadaland with libel notices for our past reporting on them and notified us of their intention to file a defamation suit.

WE’s public image revolves around one charismatic personality: Craig Kielburger, WE’s figurehead and the personification of its mission.

“He has this aura of a God.”

JORGE AMIGO, FORMER WE CONTENT STRATEGIST

His origin story is a foundational text for WE that is told and re-told to millions of kids. As it goes, Craig found his purpose in life in April 1995 at the age of 12, when he read an article about Iqbal Masih, a former child labourer in Pakistan’s carpet trade. Masih, an unlikely activist, had become a martyr after being assassinated by the “carpet mafia.” It was at that moment that Craig took up the work that Masih could not, and WE Charity (then called Free The Children) was born.

However, both local police and an NGO, the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan [pdf], soon determined that the man who killed Masih was, in fact, not connected to the carpet industry at all. Their investigations determined that Masih witnessed a man sexually assaulting a donkey, and the man then shot Masih, reportedly by accident. There were also reports that Masih was 19, not 12, at the time of his death. No one has been convicted for Masih’s killing.

In his 1998 book, Free the Children, Craig wrote about personally investigating the conflicting accounts during a trip to Pakistan, and concluded that the truth about Masih’s death was unclear — but that ultimately, the details of it were not important.

“It didn’t matter if Iqbal was 19 or if he was 12 when he was murdered,” he wrote, explaining that “all that mattered was that his work was still not over and that we were challenged to continue it.”

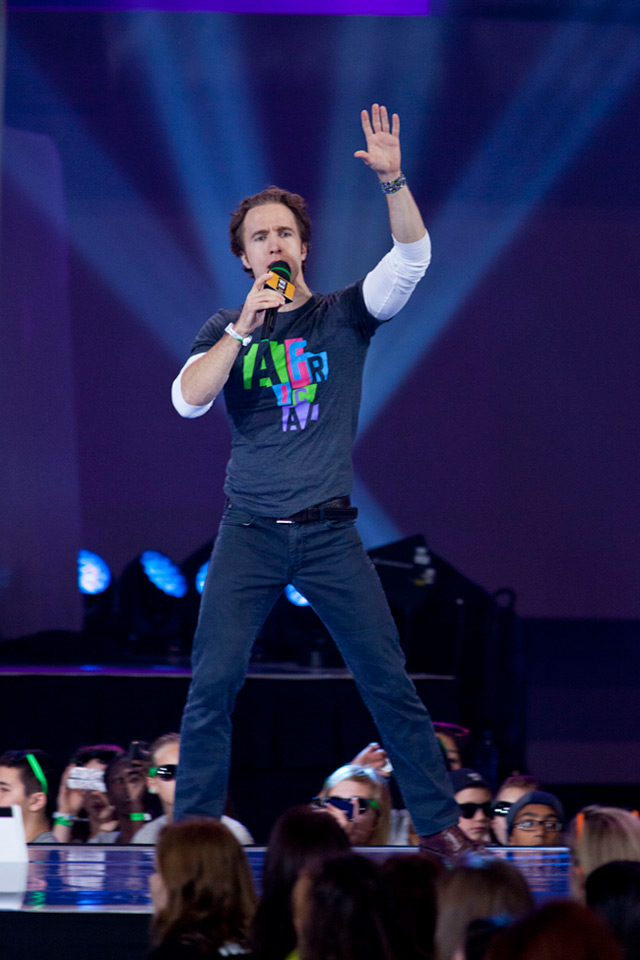

Years later, at a 2010 WE Day event, Craig was still telling the original version to an arena full of youth. “At the age of 12,” Craig said of Iqbal Masih, “he was assassinated. He was killed because he stood up, because he spoke out.” In a WE-produced video of the performance, the camera cuts away repeatedly to the faces of kids as they absorb the emotional story.

Craig’s celebrity and influence are derived from his energy and charm as much as from his origin story. One former WE volunteer, who began working with the group at age 11, called Craig’s charisma “infectious.”

“It’s incredible the way he can speak,” he said. “This is really his mission, it’s what he was put on the world to do.”

Another WE volunteer, Josh Keenan, worked for WE in high school as a co-op student and was hired back as an International Youth Coordinator in 2007, leading 200 groups in fundraising efforts, he said, at the age of 19. He remembers being starstruck upon first meeting Craig while on a volunteering trip to Kenya. “It was like, ‘Oh my God, I’m meeting and talking with Craig Kielburger,’ who was like a hero to me at that time.” He eventually became disillusioned, and his relationship with WE ended.

“He has this aura of a God,” said Jorge Amigo, a WE content strategist who left in 2014, remembering a staff retreat at which Craig made a brief appearance. “He gets on stage to deliver a speech proselytizing…telling us about all the celebrities he got to meet, and how special we should feel” for working at WE. Amigo said he remembered “feeling weird and thinking, ‘I already work here, why do they need to sell me so hard on this?'”

When asked about Amigo’s recollection of this, WE Charity executive director Dalal Al-Waheidi said, “Jorge Amigo was with the organization for approximately nine months before the Human Resources Department parted ways with him in May 2014 due to performance concerns.”

Amigo told Canadaland that he resigned from WE on his own, noting that he felt “uninspired” by his job.

If Craig is WE’s face, his older, Harvard and Oxford-educated brother Marc is considered its brains.

He’s not nearly the public figure Craig is — his Facebook page has a shade over 200 likes compared to Craig’s 59,000 — but within WE, he is considered the day-to-day leader.

“[Marc] is very concerned about loyalty,” said a former member of Marc’s executive support team.

“And he takes things extremely personally.”

A former associate director who left in 2014 said, “The culture of bullying and fear is very pervasive, and that comes directly from the founders…I’ve been yelled at by both [Marc] and Craig.”

One former manager who left in 2015 said, “Marc has so much bottled-up anger… It seeps from his pores.”

One former employee claimed that Marc had an outburst after someone made a spelling error. A former coordinator said Craig yelled at them because other speakers “had more speaking time than him” at an event.

“[Marc] has used expletives, sworn in front of staff members, subordinates,” said Marc’s former executive support staffer.

All told, 10 former employees said Marc had a notorious temper, with three saying they had been yelled at directly by him. Another two former employees said Craig had yelled at them.

WE vigorously rejected these accounts and characterizations, and provided Canadaland with signed testimonials about the good character of Marc and Craig written by WE Charity’s board of directors.

Michelle Douglas, the chair of WE Charity’s board, said that “Craig and Marc are among the most compassionate people I know.” WE consultant David Baum said the brothers “are tireless, working harder than anyone else, bringing passion, smartness, and an extraordinary vision to almost every endeavor.…I have been most impressed with their central humility.”

“Craig and Marc are among the most compassionate people I know.”

MICHELLE DOUGLAS, WE CHARITY BOARD CHAIR

WE provided a reference letter for Marc signed by 10 current and former employees, which said that “he has proven again and again to be a dedicated, level-headed leader who treats colleagues of all levels with respect and humility. This is both in times of ordinary daily engagement or in times of high-pressure situations. Any indication otherwise would be incorrect.”

WE also provided a similar letter about Craig, from five current employees and one former employee, which said that “he is calm, clear, and patient in all situations.”

According to Josh Keenan, Marc “could be mean, from just out of nowhere. He’d go from zero to 100 in terms of kind of chastising.” He said that on multiple occasions, he heard Marc berating people in his office. He said, “It all felt kind of ridiculous,” given the unpaid overtime people were working.

“The culture of bullying and fear is very pervasive”

FORMER WE ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR

When asked about Keenan’s account, WE provided a statement from WE Charity’s educational partnerships director, Greg Rogers, who taught both Marc and Keenan in high school and arranged Keenan’s initial placement with WE. He questioned how “after more than 12 years, a former teenaged high school co-op student, who was part of the WE team for just a handful of months, has such specific memories of what would have been very limited, if not zero, interaction with the co-founder.”

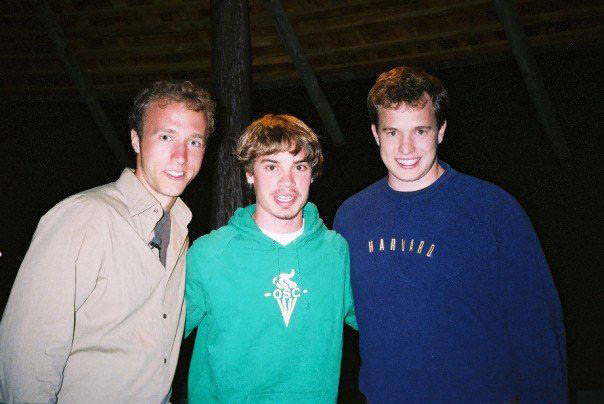

A photo on Josh Keenan’s Facebook page shows him with Craig and Marc Kielburger.

Rogers also said that WE “closely monitor hours and work conditions” and that based on his own experience, Keenan’s description of “the work environment and demeanor of the co-founder are not accurate.”

WE also provided Canadaland with an “independent review” of the organization based on interviews with more than 100 of their current and former employees [pdf]. This independent review was conducted by “conversation architect” David Baum, an organizational psychologist. Baum is also a longtime mentor to Craig and Marc, and presided over the ceremony at Craig’s wedding, but has emphasized that his reports were prepared “in an independent and unbiased capacity.”

Baum also said the brothers “hand-write birthday cards and congratulatory notes [for employees], attend staff weddings and family funerals, visit employees in the hospital…They are among the most dedicated, caring, and loyal leaders I have encountered in my three decades of experience.”

For many years, properties owned by WE in Toronto’s Cabbagetown neighbourhood housed entry-level employees. WE said the program was fully phased out over five years ago.

The communal homes were, by some accounts, exciting places for young coworkers who were immersed in WE’s culture. “It was fun living there,” recalls one former resident. “We had fun, and we worked.”

However, burnout and attrition rates were high, said former employees, due to the demanding work schedules and low pay. But workers who lived in WE housing were particularly precarious. “A lot of people…their lifestyles were reliant on the fact of them having free housing,” remembered Keenan, who did not live in the housing but described those who did as having been “kind of dependent” on the organization. “It cultivated this very odd atmosphere.”

In a statement provided by WE concerning staff attrition, chief people officer Victoria MacDonald said that these days, “new entry-level employees stay with the organization, on average, for 2.4 years,” which she said is “significantly longer than the industry norm,” citing data from LinkedIn.

MacDonald also said that “more than 100 WE employees have been with the organization between 8-20 years.”

When Dan Mossip-Balkwill left his job as a WE manager in 2009, he also lost his home.

Leaving meant vacating the WE-owned house he shared with his co-workers. He wrote a parting letter listing the ways in which he felt WE’s culture was broken, and sent it to hundreds of colleagues, including management.

“I’m tired of being made to feel guilty about asking to be paid a living wage, because that money would otherwise go to ‘educate starving students in Africa.’”

DAN MOSSIP-BALKWILL, IN 2009 EXIT EMAIL

He brought up worker safety concerns, and wrote at length about the problems, as he saw them, with WE’s “culture of guilt.”

“I’m tired of being made to feel guilty about doing expense reports,” he wrote, “or asking to be paid a living wage, because that money would otherwise go to ‘educate starving students in Africa.’”

Mossip-Balkwill also said in his letter that “to reduce [employees] to tears, tell them to leave if they don’t like it, that they need to suck it up, or that their problems don’t compare to children in Africa is atrocious.”

He also raised a concern about ME to WE, the for-profit “social enterprise” which had launched just a year earlier.

“ME to WE was supposed to redefine business,” Mossip-Balkwill wrote. “Instead it became another private-sector company whose number-one aim is money, where people and staff come second.”

Mossip-Balkwill concluded by saying that he was writing out of love, and not out of a desire to “take down” the organization. He wrote that he hoped his letter would inspire WE to change.

In a statement to Canadaland, WE recently said that Mossip-Balkwill’s letter had done just that.

“Ten years ago, the organization used this email, as we do any feedback, as an opportunity to build upon existing conversations with its staff regarding continuous internal improvement,” said ME to WE executive director Russ McLeod.

McLeod said that at the time, “the organization was going through a transformation from a youth-driven grassroots charity, to a professional organization.” In this period, he said, “there were continued investments and modifications” in areas such as transportation and travel accommodations, as well as “a greater investment in human resources, management, and training, and additional workplace wellbeing programs.”

“…work-life balance will likely require deliberate management on an ongoing basis.”

HR CONSULTANCY LHH KNIGHTSBRIDGE

WE has also pointed to the results of an anonymous employee survey conducted by TemboStatus, with 900 respondents. According to WE, TemboStatus found that from 2015-18, employees reported enhancements in work-life balance (a 2.85-times improvement) and in providing “adequate compensation” (a 5.33-times improvement).

Canadaland asked more recent WE employees to review Mossip-Balkwill’s 2009 exit email.

“It’s almost eerie that people talked that way so long before I started, and still do now,” said a former employee, who left in 2017.

ME to WE was “first and foremost about money, despite its noble beginnings,” an associate director who left in 2014 agreed.

Dan Mossip-Balkwill’s email on Scribd

WE’s workers “joined for minimum wage and worked around the clock,” according to the organization’s own case study of its HR history, with reference to the organization’s early period, 1995-2003.

“I was working 60-70 hour weeks” during the busiest periods, remembered Keenan, who joined in 2007. “It was gruelling at points.” He said overtime hours were not recorded, and no time in lieu was provided to offset it.

Keenan said that his true hourly wage at WE, once all working hours were counted, would have been under minimum wage at the time, but “they got away with it” because employees were paid an annual salary.

While recognizing the two situations were not actually comparable, he said that he and his colleagues would joke about the irony of an organization that works to combat child slavery having such a problem with young, underpaid employees.

In its self-produced case study, WE said that “16-hour shifts were the norm in the days leading up” to the first WE Days in the late 2000s.

But these days, they said in a statement to Canadaland, “Non-management employees typically work eight hours a day, Monday to Friday.”

“I don’t ever remember taking a lieu day,” remembered one former manager who left in 2015. “I was never asked to submit time sheets for myself or my staff.” Asked why she left WE, the former manager said, “I was too broke to work there…and still had to wait tables to pay bills while being on the WE Day 24-hour work cycle.”

A former coordinator who worked for ME to WE from 2010-11 told Canadaland that she “was waitressing at the time on weekends because she “couldn’t afford to go by on their wage.”

“It was like 60-hour weeks,” she said. “It was ridiculously long hours. And I think they did that deliberately because they could guilt their employees, in that ‘it’s charity, you’re passionate. This is a calling, if you really cared about making a difference, it wouldn’t be a problem that you’re working a 60-hour week.’”

Keenan said that if employees complained, “It would be brought up in front of people — ‘You’re not as committed, you’re not one of the high-profile people that is really trying to make a change in the world.’”

A former coordinator who left in 2014 said, “I was yelled at by my manager in front of my entire team and called lazy and incompetent and was told I wasn’t good at my job, and I wasn’t a ‘culture fit’ because I wasn’t able to work [one] weekend.”

“The organization was going through a transformation from a youth-driven grassroots charity, to a professional organization.”

RUSS McLEOD, ME TO WE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, ON 2009-10 PERIOD

According to WE, the recent TemboStatus survey found that 98 per cent of their employees “believe they are making a positive change in the world because of their work” and that 78 per cent say they “love their job.”

“For me, it’s been an amazing opportunity to learn, to grow, to be mentored by amazing individuals across the company,” Calvin Mitchell, the senior supervising producer for WE Day, said in an interview with Canadaland. Mitchell has been with WE for nine years.

“I love what we do,” he said. “I love that we’re able to make an impact every day.”

When asked if WE had ever expected employees to work weekends, evenings, or other overtime without compensation, WE answered in the present tense that “it would be factually incorrect to claim and/or imply that WE is not complying with jurisdictional labour laws.” WE told us that their current practice is to give employees time in lieu to compensate for heavy periods of work at night or on weekends.

WE also told Canadaland that, today, they pay entry-level employees a base salary of $35,000/year plus benefits they value at $5,000, which they said is in line with industry norms for non-profits.

According to WE, in 2018 Craig and Marc Kielburger each received a salary of $125,173, paid by ME to WE, the organization’s business wing. WE also said that non-profit consultancy KCI had determined that the co-founders’ compensation was “within the typical range” for executive positions in similar organizations.

WE told Canadaland that if either brother wanted to take a job in the for-profit sector, their education and experience is such that each would likely be paid “more than four to five times” their current salary.

WE’s emphasis on keeping overhead low and costs to a minimum sometimes had an impact on employee safety, according to former employees.

A former outreach coordinator who left WE in 2009 would use her own car to travel to different schools in Ontario to give speeches for WE. She said that the organization would not pay for her to sleep in a hotel, so she would often make a trip to another city as far as four and a half hours away, deliver a speech, and drive home, all in the same day.

“I have almost fallen asleep at the wheel multiple times,” she recalled. “I had to pull over and take quick naps on the side of the road because I couldn’t continue.”

Another time, she slept on the couch of a teacher who worked at a school she was visiting.

“We would go, go go,” she said. “If you didn’t, you’d feel guilty…The mission was so important.”

WE Charity executive director Al-Waheidi told Canadaland in a statement that “the concept of billeting at the homes of local teachers and supporters is commonplace among many non-profits seeking to be as efficient as possible with scar[c]e resources, nonetheless this practice was ended 10 years ago.” WE also said that more than a decade ago, they implemented a policy to reimburse employees for travel expenses when workers need to pay to get home for safety purposes.

According to one former volunteer, the practice of WE employees and volunteers lending each other a couch when needed had at least one bad outcome.

In 2010, an 18-year-old who was volunteering for WE at the time let a WE motivational speaker crash in her Vancouver dorm room for several nights, after he requested accommodation between work engagements. She claimed that he sexually harassed her during his visit.

“A question I ask myself now,” she said in a recent email to Canadaland, “is, why did he need to ask to stay with me?”

“But I was 18,” she continued, “and I probably didn’t question it because ME to WE/Free The Children was already this weird organization where boundaries were crossed all the time. I didn’t have other professional experience to understand that it wasn’t normal. Or that it would be dangerous for me as a young girl to welcome an older male staffer into my residence.”

Canadaland contacted the former WE speaker. He denied any allegation of sexual harassment, and said, “Although I feel strongly on this matter, I also respect that I cannot understand how others view matters, and if anyone ever felt that I did anything inappropriate, then I sincerely apologize to them.”

When asked about this incident, WE said, “This allegation was never brought to the attention of anyone in management or our Human Resources team….this alleged incident of unwanted advancements took place after work hours in a non-work environment 10 years ago. The person in question was not in a management role and was not responsible for any direct reports.”

(content warning: the following paragraph contains a description of an alleged sexual assault)

One of the perks available to WE employees, according to WE’s “Employee Value Proposition,” is “opportunities to interact with and learn from WE’s celebrity ambassadors.” Until recently, the band Hedley was among WE’s “celebrity ambassadors.” In 2018, lead singer Jacob Hoggard was arrested and charged with sexual assault following allegations from a woman who was reported by the CBC to be a WE Day volunteer. The CBC reported she first encountered Hoggard in 2016 during a WE Day in Ottawa. WE disputed this, saying that they did not meet in person at WE Day Ottawa. The woman alleged that she was later “demeaned, choked, and forced to have vaginal and anal sex.” Hoggard has denied the allegations.

“If any of our staff were impacted by the situation, they could contact Human Resources”

WE

WE immediately cut off all ties to Hedley and communicated to their employees that “if any of our staff were impacted by the situation, they could contact Human Resources via the formal and anonymous reporting systems.”

A former communications staffer at WE said that well before the allegations were made, she was told by coworkers to avoid Hoggard, who she said had attended WE holiday parties and visited the organization’s offices.

WE told Canadaland that they “only learned of the allegations through the media coverage at the time, and WE had no prior knowledge of the alleged actions of Mr. Hoggard.”

Canadaland asked WE if the organization conducted an internal investigation to see if any of their employees or volunteers alleged that they had been harmed by Hoggard.

WE said that “when any formal or anonymous reporting takes place, a full investigation is conducted.”

WE said that no such reporting took place.

Several former employees who spoke to Canadaland said they left WE after being put in ethical binds, with some saying they became “disillusioned” with WE.

A former educational programming coordinator, who left WE within the last six years, grew uncomfortable with the methods she said she was expected to use in leading Canadian schoolchildren on fundraising campaigns.

“It was always about the bottom line,” said the former coordinator, who had begun her own relationship with WE in high school as a young volunteer.

On one occasion, following her manager’s instructions, she led a fundraising campaign with a class in Canada. Using a motivational technique common among charities, she told the students that if they hit their target, a specific school would be constructed abroad.

“We would send them updates,” she recalled, “we would send them photos, and we would send them all this information.”

“The information we had been telling these students was completely made up.”

FORMER WE EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMMING COORDINATOR

She said that it was only when the class asked to take a trip to the school that “we were told that that school didn’t actually exist for that funder. So the money was not going to that school. The school hadn’t even been built yet.”

“And so the information we had been telling these students was completely made up,” she said.

She felt that her own manager was under pressure from higher-ups to meet aggressive fundraising targets.

“Managers were put in an untenable situation where they were just at their wits’ end,” she said. “So they used every and all tactics to try and get their staff to raise more and raise more, and the bar was always shifting higher and higher.”

WE Charity’s Al-Waheidi told Canadaland in a statement that WE fundraises to support entire villages, and that “there is no building of ‘one specific school’ in isolation in a village.” Additionally, two WE Schools executives said in joint statements that the former coordinator’s claim was “nonsensical,” “incorrect,” and “misleading,” stating that school groups can visit the villages they support, but some construction projects “may require a couple years until construction is complete.”

Another former employee, who worked as an associate director for WE, said North American school kids were “almost like a commodity” for the organization.

Carrie Patterson, the chief operations director for WE Charity and WE Schools said in a statement provided by WE that “the majority of WE’s campaigns (70 per cent) are focused on student service, not fundraising” and that “unlike virtually any other charity, WE actively encourages and supports youth to raise millions of dollars for other causes and charities.”

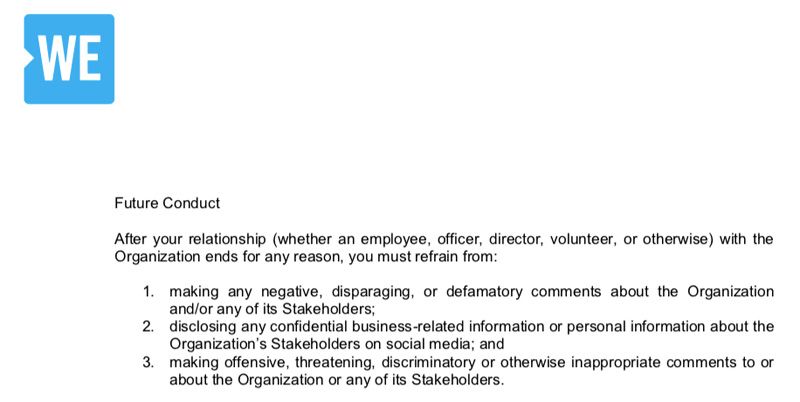

WE’s rules and policies prohibit employees from speaking critically about the organization to outsiders.

“Employees who do participate in ‘gossip,’ whether as speakers or active listeners, may be subject to immediate dismissal.”

WE

“Employees shall not ‘gossip,'” reads a series of rules and regulations that a new employee had to agree to in 2017. This language has been communicated by WE to employees since at least 2009.

“Employees who do participate in ‘gossip,’” the document continued, “whether as speakers or active listeners, may be subject to immediate dismissal. This procedure is especially relevant with sharing sensitive information to individuals outside the organization.”

A 2017 WE Charity employment contract had additional secrecy provisions, placing limits on the speech of employees after they have left the organization, seemingly in perpetuity.

The employee must agree that both while working for the organization and after leaving it, they “shall not make, post, or publish” derogatory comments or opinions about WE or its representatives “in any form whatsoever.”

The gag order had no expiry date, and the contract laid out financial consequences for violations; it held the employee’s heirs and successors liable should the employee die after breaking the terms.

In a statement provided by WE, chief people officer Victoria MacDonald said the organization’s employment contracts “contain many standard boilerplate clauses, including non-disclosure agreements and non-disparagement provisions, that are commonly found in most employment agreements in professional environments.”

WE has employed over 2,000 people. It solicits donations and volunteer work from the public and engages with kids in thousands of public schools. It receives government funding. It is a thoroughly public enterprise, and the public has a clear interest in knowing about WE.

Canadaland first reported on WE in March of 2015, after a documentary critical of the organization was pulled from the CBC’s television schedule the day it was set to air. Canadaland learned that the CBC scrubbed the documentary of negative comments about WE and re-scheduled it for broadcast, after WE contacted the CBC to raise concerns about what they described to Canadaland as “unauthorized footage” of a WE Day event. (In comments to Canadaland at the time, a WE spokesperson emphasized that they “did not ask for the documentary to be pulled.”)

Once Canadaland published stories on this incident, WE employees past and present began contacting us with information. Our investigation has been ongoing ever since.

In responding to questions posed for this article, WE offered extensive volumes of statements and material from current and past senior staff, board members, subject-matter experts, groups they’ve helped, and consultants. They also included three assessments from former Ontario Court of Appeal Justice Stephen Goudge evaluating different aspects of the organization’s practices; six further human-resource reviews and case studies; positive testimonials from more than 100 former staff members; reports on safety practises both domestically and abroad; and letters from a former prime minister of Canada, a former governor of Wisconsin [pdf], and a psychiatry professor who late last year was appointed to the Canadian Senate.

Over the last eight and a half months, the WE organization and members of the Kielburger family have accused Canadaland of “malice,” “recklessness,” and “an astounding level of hostility,” of “harassing and attempting to attack” members of the Kielburger family, and of fabricating images in our articles.

“It’s almost eerie that people talked that way so long before I started, and still do now.”

FORMER WE EMPLOYEE

They have retained lawyers from six different firms; sent two notices of libel; announced an intention to commence litigation against Canadaland in Manitoba (a province that, unlike Ontario, where both WE and Canadaland are based, does not have anti-SLAPP laws); enlisted a retired judge, the aforementioned Justice Goudge, to review our reporting and render a “verdict” on it; and stated that they possess a video recording of what they suggest is a Canadaland representative visiting a house belonging to Kielburger family members — “trespassing on their property and stalking people who live at houses owned privately by these individuals, in an effort to get additional information and scaring the families living therein.” They said that they have “concern for their safety” and that they may “contact the authorities” if the incident they alleged should recur.

(Canadaland once visited a house, known to have formerly been a WE employee residence, that now operates as an unrelated business where no Kielburger family members were known by Canadaland to reside. Our reporter knocked on the front door. No one answered, and he left.)

WE said that Craig Kielburger was “accosted and pursued by someone who self-described himself as ‘a follower of Canadaland.’” And a WE department head circulated a Postmedia syndicated op-ed by a DC-based Republican operative who called Canadaland “fake news.”

WE has changed, according to WE.

In David Baum’s independent report, provided by WE to Canadaland, Baum wrote that by the early 2010s, “The organization was growing up, figuratively and literally.” He noted that today, “work and sweat are no longer the sole measure of commitment.”

Baum also said that WE’s leadership makes efforts to improve themselves.

“WE’s executive leaders’ willingness to always learn and do better cannot be understated … They undertake hundreds of hours of personal coaching, leadership training, and working with mentors to try to constantly improve as leaders and people.”

Among those who agree that WE is constantly improving is former prime minister Kim Campbell, who in March applauded WE for hiring an external firm to carry out employee surveys in an effort to improve the workplace.

“Work and sweat are no longer the sole measure of commitment”

DAVID BAUM, CONSULTANT

However, one external report commissioned by WE concluded that the organization’s issues persisted. The 2018 work-culture review by LHH Knightsbridge concluded that, as of last year, the nature of WE’s “purpose-driven” work still made it challenging for employees to maintain work-life balance, and that management was in fact not directly addressing this issue.

“Given the nature of the work and the sector,” the review recommended, “work-life balance will likely require deliberate management on an ongoing basis.”

As described earlier, WE recently told Canadaland that when Dan Mossip-Balkwill left the organization in 2009 and emailed his candid thoughts to management and staff, the organization listened to him, and took his critical letter as an opportunity for improvement.

But that’s not what WE said in 2009.

The swift response to Mossip-Balkwill came from Renée Hodgkinson, ME to WE’s then-executive director. It was emailed to everyone who had received the initial exit email. Dan Mossip-Balkwill was not sent a copy.

Hodgkinson wrote that she read Mossip-Balkwill’s exit letter “with great sadness” because it was “extremely inaccurate, lacks courage, and does not embody any qualities of leadership.”

Renée Hodgkinson response to Dan Mossip-Balkwill email on Scribd

She did not directly respond to his most serious points, such as his feeling that management asked employees to remain silent about important issues for the greater good of the WE mission.

Instead, Hodgkinson requested that staff keep Mossip-Balkwill’s words to themselves.

“We ask you to not share this email with anyone,” she wrote, “as we need to be mindful of the potentially challenging impact it could have for stakeholders, supporters, and especially young people who are active in our programs.”

She wrote that WE would soon have a “tremendous global impact” and transform hundreds of thousands of young lives.

“We are about to verge on something so special.”

With additional reporting by Jesse Brown.