In late November 2014, Frances Willick, then the education reporter for the Halifax Chronicle Herald, was assigned to cover the local WE Day at the city’s Scotiabank Centre arena. The event was a multimedia extravaganza to reward and energize 8,000 kids for their volunteer work.

What she saw there made her skeptical.

In a series of snarky tweets, Willick raised an eyebrow at everything from the celebrity speeches to what she viewed as the corporate influence over the show’s content. She expressed curiosity about the funding behind WE Day and the financial structure of the organization that staged it. Willick took particular note of how she, as a reporter, felt carefully monitored at the event.

Media are so tightly managed by an army of PR students that we are escorted even to the bathroom (they wait outside til you're done).

— Frances Willick (@fwillick) November 28, 2014

I went up a couple of rows into the stands to interview some kids and was tailed by my escort – just in case I "get lost."

— Frances Willick (@fwillick) November 28, 2014

I'm not even joking when I say that media are more tightly controlled at We Day than at the Halifax International Security Forum.

— Frances Willick (@fwillick) November 28, 2014

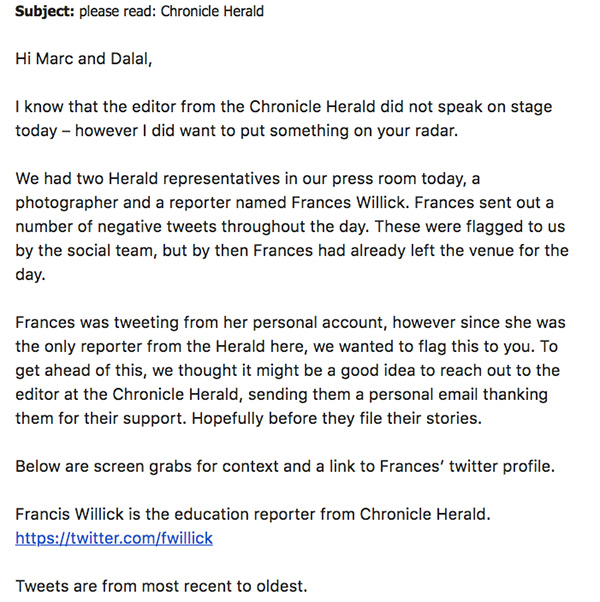

Willick’s tweets were quickly noticed by WE.

Alison Clarke, WE’s associate director of public relations, emailed co-founder Marc Kielburger and others, flagging the tweets in an effort to “get ahead of” what might be coming, suggesting they send a “personal email” to the newspaper’s editor “thanking them for their support.”

The Chronicle Herald, after all, was a WE Day media partner.

“Hopefully,” Clarke wrote, the email would be sent “before they file their stories.”

Willick tells CANADALAND that she soon received a call from Sarah Dennis, the paper’s publisher and owner.

“All I remember of the conversation,” she says, “is that she told me that the WE folks had contacted her because they had seen my tweets.”

Willick says there “were no negative repercussions” for her as an employee of the newspaper. Dennis did not respond to a request for comment. (The tweets remain online.)

Last year, the We Day folks didn't like my tweets. I had linked to critical articles & CRA info. They called the publisher of the paper.

— Frances Willick (@fwillick) November 20, 2015

Willick’s piece ran as a glowing recap online that evening and in the paper the next day. “The crowd was as pumped as the decibels inside the Scotiabank Centre,” it declared, “as about 8,000 young people from across Atlantic Canada gathered for a day of inspiration and music.”

None of her skepticism was included. And neither was her name — the piece was published without a byline. Willick says she doesn’t remember why.

When asked about the email suggesting contact with Willick’s superior and about the claim that that did occur, WE denies that any contact was made. In a written statement, WE’s lawyer Peter Downard says, “At no time were my clients in contact from the editor-in-chief, publisher, or any other senior management at the Chronicle Herald in this matter. Furthermore, at no point did my clients authorize anyone to make contact with the editor-in-chief or any other senior management at the Chronicle Herald on their behalf.”

WE also tells CANADALAND that any assertion that they had ever sought to suppress the publication of critical news stories through direct contact with executives who work for their media partners would be “factually inaccurate, and defamatory.”

The WE Movement — which includes WE Charity and ME to WE, the business arm that donates half its profits back to the charity and reinvests the rest in itself — has enjoyed “overwhelmingly positive media coverage” over the last 20 years, according to a recent internal email from its executives.

Co-founders Craig and Marc Kielburger have appeared on Oprah and 60 Minutes. Marc once appeared on The Colbert Report, and Craig even turned up on a 2011 episode of MTV Cribs, on which he showed off WE’s Kenya volunteer camp and, in a seeming gesture toward embracing local custom, drank the blood of a cow.

The Globe and Mail has explained how “High-octane We Day Toronto sparks young minds.” Toronto Life has gone “Inside WE’s new high-tech Global Learning Centre with Skype pods, a wellness room and 39 microclimate zones.” Even Marc Kielburger’s marriage to ME to WE CEO Roxanne Joyal was written up in the Toronto Star, under the headline “Their love is built on helping others.”

Many of the same media outlets tasked with covering the WE Movement are also partnered with it. The website for WE Charity, which until 2016 was known as Free the Children, lists 38 official media partners in Canada and the United States, including newspapers, magazines, radio stations, and TV networks; other outlets are placed on a separate list of corporate partners. Those relationships have given WE, and the Kielburgers, a massive platform with which to promote their work.

WE Day is broadcast on CTV in Canada and ABC in the U.S. Senior leadership from WE’s media partners have spoken at WE Day events.

Sometimes, readers of Canadian dailies like the Globe, Winnipeg Free Press, and various Postmedia papers will find a WE-themed special section in print, which includes content created by WE employees. WE also produces advertorial content for media partners outside of the special sections. They work with the Globe on a media-literacy initiative.

The brothers have also become some of the country’s most widely published newspaper columnists: Craig and Marc have been given, at various times since 2006, regular dedicated spaces to write in the Toronto Star, Globe and Mail, and assorted Postmedia dailies. In those columns, they’ve mused about everything from memes to poverty to the blockchain. Their current Postmedia column shows up in at least two dozen Canadian papers each week.

According to four former WE employees, staff at WE ghostwrite the Kielburgers’ op-eds as well as books. In a statement, WE says that “while Craig and/or Marc Kielburger are deeply involved in each column,” they “depend on the support of staff.” WE did not respond to a subsequent question asking about books.

One effect of a media outlet having a formal partnership with an organization is that it could potentially create conflicts when it comes to covering that organization critically.

WE states, “Our media partners do not seek to influence or control WE content, nor do we interfere with their journalistic responsibility to report the news.”

But for years, Canadian newsrooms have raised questions about WE, a public-facing institution that employs over 1,000 people and is active in 16,000 schools. In multiple circumstances, reporters have pursued stories with the intention of critically exploring various aspects of WE — yet if you search for any negative, critical, or even skeptical coverage about the WE Movement’s voluntourism trips, corporate structure, corporate relationships, or educational programs, you’ll find virtually nothing.

Nearly two dozen sources, comprising journalists and former WE employees, have described to CANADALAND a concerted effort by WE to meticulously — and sometimes forcefully — manage their media profile to mitigate and minimize criticism.

WE, which works to end global poverty and improve the lives of children, tells CANADALAND that it partners with media outlets to “generate public awareness on issues of importance, and also support the broadcasting and promotion of WE Day to expand its reach to youth and families.”

Former employees who worked in partnerships at WE — and who requested anonymity because they say they want to avoid retribution for speaking to CANADALAND — say it’s about good publicity.

“They definitely view their relationships [with media outlets] as they should get more access, or more privilege,” in terms of coverage, says one. Positive coverage “was definitely a goal of the partnerships, though not written into contract,” says another.

“Over the years, I’ve spoken to four or five reporters who’ve been chasing [a story about WE]… but nobody seems to have gotten very far with it,” says a former senior employee of a magazine once sued by Craig, who requested anonymity, citing fear of retribution.

On the rare occasions when critical items have been published, WE has often responded aggressively, showing little patience for dissenting opinions or facts that challenge their virtuous public image.

(WE recently served CANADALAND with a notice of libel concerning an October report that raised questions about some of the corporations with which it partners. The organization has also declined to respond to most questions put to it by CANADALAND for this story, with WE’s lawyer, Peter Downard, informing our own lawyer that “given the litigation pending between our respective clients, I have advised them that they should not reply to Mr. Kerr’s email to them of today. Our clients’ libel notice served on your clients makes plain the many errors that your clients have already published about them, and our clients’ deep concern about your clients’ apparent hostility toward them. Your clients continue to refuse to put to our clients, fairly and squarely, allegations about our clients that they intend to publish.” CANADALAND stands by its reporting.)

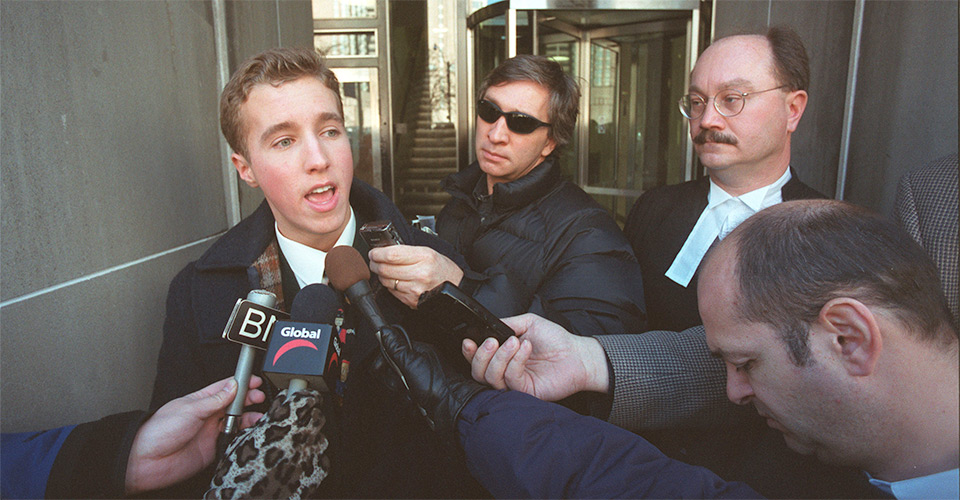

Craig’s first major run-in with negative press came in November of 1996. The now-defunct Saturday Night magazine ran a cover story about the young activist titled “The Most Powerful 13-Year-Old in the World,” praising Craig’s activism and lauding him as a “great orator.” But the story also gave voice to Kielburger’s critics.

“The image of this earnest, articulate eighth-grader sparring with the prime minister on child labour seemed too good to be true. In the Canadian press corps, some cynical journalists gave Craig the nickname Damien,” the profile said.

Craig did not like the piece.

“Saturday Night can use their magazine to mock me and to make fun of Free the Children and our intentions,” he said at a press conference where he announced his intention to sue the Canadian monthly. “But they must and will be held accountable for the damaging lies which they represent as being truths.”

In January of 1997, after having just turned 14, Kielburger filed suit, seeking $3 million in damages.

“My experience with [the Kielburgers] was actually very nice until I found myself on the other side of a lawsuit,” Isabel Vincent, the writer of the piece, told CANADALAND in July. “It didn’t seem like they wanted to deal with any kind of criticism, no matter how slight,” she said.

“I don’t think the story took away from the fact that he was a pretty special kid, and that he was doing something pretty courageous and awesome.”

One major focus of the suit was a passage about where donations to Free the Children ended up. Vincent had written “the money goes directly to the Kielburger family. Free the Children is not a legally registered charity in Canada. Mrs. Kielburger says that they are in the process of applying for registered status.”

Kielburger said in his claim that that was false and led people to wrongly believe he was keeping the money for himself. (According to a reported statement by a Free the Children accountant, donations made prior to the organization becoming a registered charity were deposited in a separate bank account, and the group was being run as a charity pending Revenue Canada’s approval of its application.) He also argued that the “Damien” nickname was meant to suggest that he was “a sinister and evil person capable of acts like the character” in The Omen series.

In addition to Saturday Night magazine itself, those named in the suit included Vincent, editor Ken Whyte, the publication’s art director, one of its researchers, and the photographer who took the image for the cover.

In the libel notice delivered to CANADALAND, lawyer Peter Downard stated that the January 1997 action against Saturday Night “represents our client’s one and only lawsuit against media.”

But the following month, Kielburger sued the Ottawa Citizen, alleging that a column that reviewed the Saturday Night story had repeated its libellous accusations.

Asked to explain the apparent discrepancy, Downard writes that “our clients’ notice of libel to the Ottawa Citizen, more than 20 years ago, related to the Saturday Night libel, which the Citizen republished. It would be inaccurate for Canadaland to report that our clients have delivered a notice of libel relating to a libel in addition to the Saturday Night libel prior to our clients’ delivery of their libel notice to Canadaland.”

Vincent, who now works as an investigative reporter for the New York Post, says she didn’t mean to insinuate criminality in the passage about donations. “My point was that it was like it had grown so exponentially in such a short period of time that it kind of caught them off guard,” she says.

“They asked for us to retract the whole story, and we said no,” recalls the former senior staffer at the magazine. “Eventually, they filed suit alleging all kinds of problems, but really it came down to just this one issue.”

In January 2000, the magazine settled. “Young crusader wins $319,000 in lawsuit against Saturday Night: Kielburger plans to use money in child labour fight,” the Star trumpeted.

Whyte, Saturday Night’s editor at the time the piece was published, told The Globe and Mail that the settlement was “largely a commercial decision,” because the suit was costing too much “time and money” and “it was time to wind things up.”

Though it was nominated for a National Magazine Award in 1997, not everyone in the press had been a fan of Vincent’s piece. Following the settlement, Heather Mallick wrote in the Globe that Craig — who she said had “won” the libel suit — “was tormented by the article’s insults directed at his family.”

In a 2002 profile of Kielburger for the Citizen, feature writer Shelley Page wrote that Saturday Night had “savaged [Craig] and his family.” The piece also noted that the suit against the Citizen had been resolved “following an apology and a donation” to the charity.

Page would go on to collaborate with the Kielburgers on two of their books. When she left the Citizen in 2012, Page joined the WE organization full-time, where she is now its Head of Storytelling, Editorial & Strategic Communications.

In addition to Page, former longtime Citizen journalist Sue Allan also works for WE in an editorial capacity, as director of content and strategy. Sandra Martin, the former editor of Canadian Living magazine, is now the head of WE Families. And Eric Morrison, the former CEO of the Canadian Press, serves on WE Charity’s Canadian board.

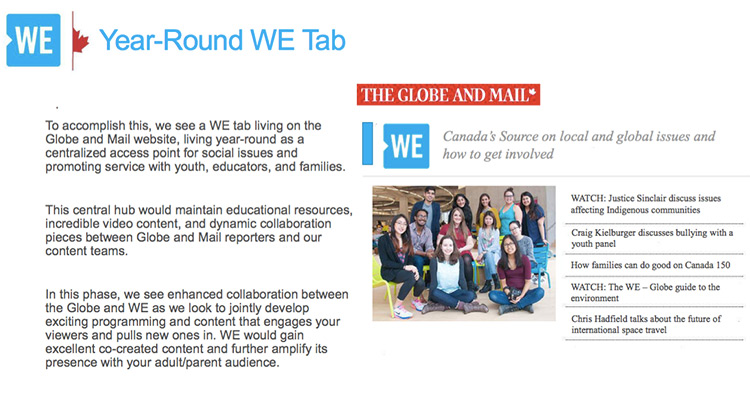

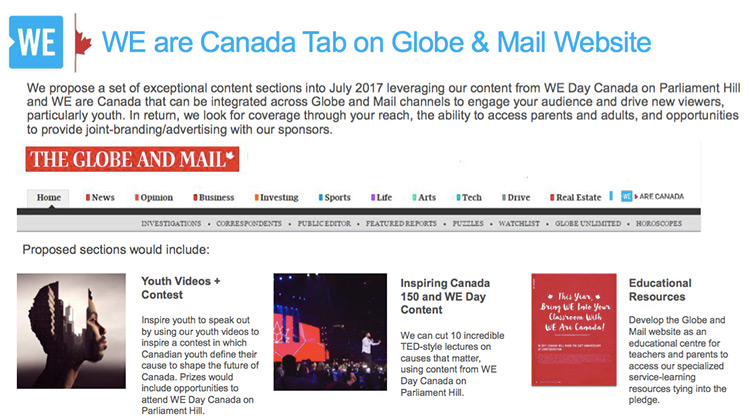

In spring 2017, WE sought to formalize one of its media partnerships in a big way. In a presentation deck obtained by CANADALAND, the organization outlined a pitch to The Globe and Mail for a “year-round WE tab,” which would appear on the newspaper’s website.

“We see a WE tab living on the Globe and Mail website, living year-round as a centralized access point for social issues and promoting service with youth, educators, and families,” the presentation said.

Archived pages on the Wayback Machine show a “Living WE” section on the Globe’s website on Canada Day 2017. CANADALAND has not found evidence of a tab having appeared at the top of the site. The Globe did not respond to a request for comment.

“There was quite a bit of pushback from the Globe,” a former WE employee says. “Not from the senior team of course, but from actual writers.” A WE tab would visually signify that WE-related content would hold the same weight as the Globe’s other sections, like Sports and Real Estate.

Among its other ideas for integration, WE’s pitch deck suggested an opportunity for “dynamic collaboration pieces between Globe and Mail reporters and our content teams.”

“WE would gain excellent co-created content and further amplify its presence with your adult/parent audience.”

A former WE employee who worked in partnerships expresses concern about the Globe collaboration. “How could we create a partnership with a newspaper and have that newspaper ostensibly be objective in covering news related to our organization?” they ask.

Former employees have also questioned the legitimacy of an award that WE Charity received from Good Housekeeping magazine, with which WE also has a partnership. In August 2017, the publication awarded WE Charity its inaugural Good Housekeeping Humanitarian Seal. CANADALAND has been unable to find evidence of any subsequent recipients.

“Good Housekeeping created an award so that [WE Charity] could be the first people to have it, and it’s just advertising,” says a former employee who worked in partnerships.

In a statement, WE says the award “was solely created and led” by Good Housekeeping. The magazine’s PR team did not respond to multiple requests for comment. In the book WEconomy, Marc Kielburger wrote that Good Housekeeping saw the award as an “opportunity to expand the partnership” they already had with WE, explaining that they “scrutinized” the charity’s operations before granting it.

“It’s not a cash transaction, it’s a priceless testimonial,” he wrote.

In 2013, Alison Atkinson, a teacher in British Columbia, wrote an op-ed for The Tyee, a Vancouver-based online outlet, about her issues with WE Day, an event that left her feeling “cynical, manipulated, and disengaged.”

“At times, it wasn’t clear to me whether the individual up on stage was there to sell their brand or as one of the inspirational speakers,” Atkinson wrote.

She also shared her thoughts about a WE app called We365.

“We were promised that with every download of the app, one child in the developing world would be immunized against disease,” she wrote. “I haven’t downloaded it yet, and I’m not sure what that says about me.”

In the article, Atkinson made two errors, confusing ME to WE (the company) with Free the Children (the charity) and misstating the name of the We365 app. WE also asserted that the article contained other errors. (Asked to elaborate on the additional issues, WE told CANADALAND that “other changes were requested at the time but were not made by the publisher.”)

But WE went beyond merely requesting a correction.

They called the superintendent of Atkinson’s school board and brought up the teacher’s opinion piece and its errors.

“Our intention was to ensure everyone engaged or impacted by the story was provided the correct information,” WE told CANADALAND in a statement.

They also pursued the matter with The Tyee.

At the top of Atkinson’s article is now an editor’s note that states that “a previous version of this article contained inaccurate statements.” It also links to a letter from a Free the Children executive, which criticized the “significance of the errors” and “incorrect assertions” in the article. The letter also claimed that the article still has “incorrect statements,” which are not specified.

“In their dealings with us, I don’t recall Free the Children explicitly threatening a legal action. Neither, at first, did they explicitly rule it out,” says David Beers, editor of The Tyee.

“It was, however, unusual protocol for The Tyee to link to the note from Free the Children in an editor’s note.”

Since writing the piece, several reporters have contacted Atkinson to ask about her run-in with WE.

“I feel like I probably hear from somebody once a year,” she said in August. “Notably, I’ve never seen a piece actually get published.”

One journalist who had previously pursued a story was Alexandra Shimo, a freelance reporter who attempted to write about the Kielburgers for the now-defunct Torstar weekly The Grid in 2011.

Shimo says WE management found out that a former employee was speaking to her. The source, she says, received pressure from WE to stop talking about the organization. In addition, she says staff members received an email informing them that a reporter was investigating the organization, and to not speak to the press.

“As a freelancer, I’m not going to put my neck on the line for a story that’s going to get me sued,” she says.

The story never ran.

After CANADALAND published our initial report on WE, two of their senior executives wrote an email to WE staffers, sharing their feelings about the story.

While WE Charity executive director Scott Baker and ME to WE chief operations director Russ McLeod said they took strong issue with the article, they informed their team that they saw it as a “learning opportunity.”

“We always welcome these kinds of conversations,” they continued, “and we think we should embrace this one too! We also believe in full transparency and wanted to proactively send this information to you to begin this educational conversation.”

In any event, they said they were confident that “few people” would ever read CANADALAND’s article because “this fringe group is a tiny website.”

Three weeks later, WE evidently changed its mind. CANADALAND’s article and podcast, their lawyer wrote in a notice of libel, had “been widely shared on social media channels reaching millions of followers.”

More recently, in an email from WE Schools addressed to “Valued Member[s] of the WE Family,” the organization described our story as “false content.”

“We live in an age when anyone can post anything on the internet,” they wrote. “This website may continue to post, since we are seeking legal advice to have the content removed, we will not be engaging with this website about any additional content posted.”

Prior to publication of this story (and following our submission of questions for it), a new “Media Partnerships” link appeared on the official “WE Corrects Canadaland” page.

Responses to our initial reporting on WE, from parties with no apparent connection to the Kielburgers or to the WE Movement, again led to a sharp rebuke from WE’s lawyer.

On November 17, roughly one month after our first report on the WE Movement was published, CANADALAND became the target of a seemingly unsophisticated and automated slew of critical tweets, all of which were published within a two-hour span from 33 different accounts that had joined Twitter since just last month. Each account had previously tweeted almost exclusively about WWE wrestling.

These accounts all issued criticisms with similar themes and wording. Each tweet was directed at @CANADALAND, the @WEMovement and this reporter, in the same order.

Ok Canadaland, how much did you contribute to Africa that you have the right to judge and jury others?

— Finley Spencer (@Accentaure) November 17, 2018

OMG, this attack on WE is just disgusting.

— Becky Walker (@Beckyinfielder) November 17, 2018

How about lets not give Africans anything and let them die of hunger. Is that the purpose of your article?

— Brian Reed (@Brianhillbilly) November 17, 2018

Image searches of their profile pictures reveals some depict people with different names that the names on the Twitter accounts, who live in different places than the locations listed. At the time that they launched their criticisms, five of the accounts followed no one and had no followers themselves.

I tweeted a note drawing attention to this campaign, as did CANADALAND publisher Jesse Brown. Neither of us suggested that this effort could have been connected in any way to the WE Movement itself.

Nevertheless, CANADALAND’s lawyer was contacted the next day by WE’s attorney, Peter Downard, who took strong issue with our mentions of these strange tweets.

“The clear implication is that my clients have had some responsibility for the generation of the messages,” Downard wrote. “These messages did not emanate from our clients nor were they authorized by them. Any contrary allegation or innuendo by Mr. Brown, Mr. Kerr or Canadaland will be relied on in the pending libel proceedings as further evidence of their malice toward our clients.”

Top photo: Craig Kielburger, then 17, speaks to media following a 2000 settlement with Saturday Night magazine. (Rick Eglinton / Toronto Star / Getty)

Update (December 24, 2018, at 4:43 p.m. EST): The WE organization has responded to this article and its accompanying podcast with a Notice of Libel, a pdf of which can be read here.

Clarification (December 28, 2018, at 11:01 p.m. EST): This article originally stated that Canadian dailies like The Globe and Mail, Winnipeg Free Press, and various Postmedia papers sometimes contain WE-themed special sections in print, “with content created by WE employees.” After publication of this article, WE clarified that, other than columns from Craig and Marc Kielburger, the content in the Globe’s WE sections is created by writers employed by the newspaper, which has “full authority and editorial control” over the content in those sections. WE also says it does not see, review, or approve the content in the Globe’s WE sections.