September 2017 brought an announcement heralded as surprising by even the announcers themselves: a group of National Post newsroom staff was seeking to unionize their workplace, one of Canada’s major national dailies and a bastion of outspoken conservatism since its creation by Conrad Black in 1998. Acknowledging that “some might even consider this a hell-freezes-over moment,” the organizing team for the union noted they nonetheless had as much reason to unionize as any other group of workers.

But after a months-long campaign, an overbearing response from management that included targeted buyouts and what a former staffer describes as “intimidation,” and a battle at the Ontario Labour Relations Board, hell has remained decidedly unfrozen. With a number of the union’s original organizers and supporters unable to cast ballots after taking buyouts, the Post’s unionization effort failed in late April by a vote of 31-32.

Indeed, any conflicted feelings that Post staff may have had in considering unionization were not at all apparent among management, whose roles both within the newsroom and as representatives of the Post impelled them to oppose it. They employed a mix of cajoling (such as with buyouts and raises), entreaties to preserve the paper’s uniquely collegial newsroom culture, office-wide memos decrying the havoc a union would wreak, and, according to CWA Canada President Martin O’Hanlon, one-on-one meetings between staff and management.

Former National Post staff describe a newsroom that, prior to the union drive, was besieged by frequent layoffs and buyouts, frustrated by changes to the newspaper’s cherished freewheeling spirit, and that felt betrayed by a particular one-two punch: first, the news that several top Postmedia executives had received enormous retention bonuses at a time of aggressive belt-tightening (after which many left regardless), and second, the March 2017 announcement that benefits and pensions would be curtailed significantly. (Postmedia did not return a request for comment on this story.)

Memo on impending benefits cuts at Postmedia: pic.twitter.com/fOU4eIacbT

— CANADALAND (@CANADALAND) March 9, 2017

Former employees identify three Financial Post reporters — Claire Brownell, Peter Kuitenbrouwer, and Drew Hasselback — as having been the core organizers of the effort to unionize the paper with the Canadian chapter of the Communications Workers of America. None are still working at the Post, and all three declined to speak for this story.

Daniel Kaszor, who worked at the Post until August 2017, says his understanding was that the drive began after pension contributions were cut.

“The big thing was that the amount getting paid into our RRSPs got cut, and that sort of motivated certain employees who maybe wouldn’t have been receptive to a union drive before to see that, basically, cuts were coming all over the place.”

Three other former employees, who asked to speak anonymously, all agree: after years of lean staffing and several rounds of layoffs, the cuts to benefits — as the company’s precarity loomed ever larger — was the last straw.

O’Hanlon describes the pension issue as “the biggest issue about this whole drive.”

He explains that the reduction in health benefits and pension contributions could cost a worker “tens of thousands of dollars” over the course of their career, and that, although the changes were company-wide, they only applied to Postmedia’s non-unionized employees. (Postmedia couldn’t unilaterally impose the changes on members of its unionized newsrooms, like the Toronto Sun and Ottawa Citizen, because such things have to be negotiated in bargaining.)

“Postmedia is giving the National Post staff a really sorry deal, because they can, because the newsroom is not united and standing up for itself. And that is what bothers me most about this whole thing: what bothers me most is that [CEO] Paul Godfrey and the others are lining their pockets with the money from the pockets of their employees, and that to me is an outrage.”

O’Hanlon says if the unionization effort had been successful, the workers could have gone back to Postmedia as a group and demanded to renegotiate the changes that had been foisted upon them.

The paper’s internal culture presented hurdles for the prospective union; though many reporters skew less stridently conservative than the paper’s bombastic opinion section, former workers all describe a sense that they had cultivated a uniquely flexible work culture — one on which they prided themselves and that many feared a union would endanger. Even so, many workers felt the situation had deteriorated to the point that they needed protection as a group from the vagaries of Postmedia management.

“I was concerned that it might be something where the people with the least seniority would be the first to go with layoffs, I know a lot of the newer people were concerned about that,” says one former web editor, who added that discussion about following Vice Canada’s contract model mollified those concerns for some people. “And I was concerned about rigid roles, maybe, being an issue.”

“I think that with a union structure in place, that would sort of force a culture shift to a certain extent,” Kaszor says. “And you know what, if the newsroom is on the verge of shutting down, which it might have been, because Postmedia’s shaky, then you kind of need a culture shift. But it would definitely be a culture shift.”

Management capitalized on that feeling by discussing the newsroom’s flexible culture repeatedly in anti-union emails sent to the entire newsroom, as well as in conversations that higher-ups such as Comment editor Kevin Libin held with underlings.

One former web desk reporter says she was offered a raise “out of nowhere” two or three weeks before the buyout was reopened in September, and that she found it odd because she’d had to fight hard for an earlier raise.

“It was really weird to me that they just handed me a raise. And they did this with a bunch of the young people, but selectively,” she says. “And then two or three weeks later they decided to reopen the buyout, and what we learned was that a) the raise, and b) the buyout, were both attempts to undermine the union push, because I think they had started to figure out the math was in favour of the union drive.”

In the weeks leading up to the late September vote, one former employee says, several emails were circulated by management and editors — as well as at least one non-managerial worker who took on a prominent role in the fight against the union, the Financial Post’s Terence Corcoran — arguing that workers should vote against unionizing. CANADALAND obtained and independently verified three of these messages.

One, republished in its entirety below, was sent by editor-in-chief Anne Marie Owens, who wrote that “the Post has always been a great meritocracy” standing out in “a bland and predictable journalistic landscape where seniority and paying-your-dues determined all.”

Ironically, given that these emails were sent as several seasoned veterans and young writers were leaving the company, she added that “we’ve seen a number of our competitors forced to lose the most promising young members of their staff. We’ve gained many of those talented journalists — often directed to us by their editors, devastated because they have no choice but to let go these rising stars.” Owens did not respond to an email requesting comment for this story.

The newsroom became a “very toxic environment” in the stretch leading up to the vote, one former employee who worked as both an editor and writer but was not part of the management team says, “when management started sending out these emails trying to make the case. And I don’t know where the pressure stemmed from, probably from the top, but it was very palpable.”

He points to Owens’s behaviour specifically as a sign of the rancor and division that pervaded the newsroom in the lead-up to the vote.

“If there was one thing that you can point to as a change, it was how the editor-in-chief, Anne Marie Owens, handled herself during that, and I don’t think that she handled the process well. She probably got pressures from above her…”

He describes her as someone who is usually approachable and fosters the newsroom’s sense of camaraderie. “But leading up to the vote,” he says, “it was like she was a completely different person.”

Several employees, including Kuitenbrouwer and Hasselback, left in September when buyouts were reopened for one week — a move that former employees characterized as clearly tied to the union drive. Due to the timing of their departure, the workers who left were not able to vote on the union.

One person who was not an organizer but took a buyout says, “All I have here, really, is speculation… but I think based on the timing, it was clear that it was not just coincidence that they happened to offer the buyouts when all this union stuff was going on.”

The CWA’s O’Hanlon says the timing is why he’s confident it was targeted. “Look, they didn’t offer buyouts out of the goodness of their hearts. They knew there were some people who were unhappy.”

A farewell party for the September buyout group coincided with the week of the union vote, and Libin was flown in from Alberta to, as one person puts it, “walk up and down the halls for extra intimidation.” The party itself took place outside of the office, at a bar in Yorkville, and three former employees say it was highly unusual to have Libin and other higher-ups such as National Post VP Gerry Nott at such a gathering; two noted that Libin, a prominent section editor, was discussing the union with workers, trying to dissuade them from supporting it.

“He was schmoozing people ’til the very end,” says a reporter who was among the workers taking the September buyout, “talking about [the union] and why it would be bad and would create all this rigidity and kill the creativity that made the Post so great.”

Libin was not the only powerful figure who discussed his anti-union views with workers. One former editor says Corcoran showed up to at least one information session held by the union “to stir some trouble” and that another staff member had also done so, though he could not remember who.

Corcoran says he did not attend any such meeting and that apart from the letter and a few conversations in the newsroom, he mostly kept to himself during the union drive. He referred CANADALAND to his letter to colleagues, posted online by Frank, in which he opined that the decision of two employees to first start the union drive and then leave was “baffling” and that “whether the union is approved or not makes no difference to me. But the more I thought about their buyout escapes, the sadder I became.”

When asked if a veteran newsroom member discussing such a matter might be intimidating to other employees, Corcoran says he “would be very surprised” by that, because he didn’t think anyone in the newsroom found him intimidating. He also took issue with the strategy of unionizing “against a company that is essentially losing millions of dollars’ worth of business every day, practically,” calling it “self-destructive.” When asked if he feels similarly about the executives who received retention bonuses totalling almost $2.3 million from the same poorly performing company, Corcoran says he doesn’t “know enough about the details” of the much-publicized story, but concedes it seemed “a little bit inappropriate” from a PR perspective.

The former web desk reporter notes that some of the rigidity that workers were wary of had already, in fact, been recently introduced, in the form of changes to working from home on the weekends and taking time off to appear on news programs or other work tied to the Post brand — and that those changes had been made by management even as they were warning that a union would quash the newsroom’s flexibility.

“And that had always been one of the perks of, like — we all have to pull a lot of shitty shifts, we don’t get paid as much as they do at the Star, but at least we have a more human environment. And it seemed like they were changing a lot of that.”

While those changes were being introduced, many of the initiators and supporters of the union were leaving. One former reporter describes the unionization effort as borne out of long-simmering tensions pushed to the surface. That those conditions existed in the first place, however, meant the drive’s undoing was also not far from the surface: by offering buyouts just before the vote, management apparently bet — successfully — on the most disaffected workers taking the chance to leave with some cushion.

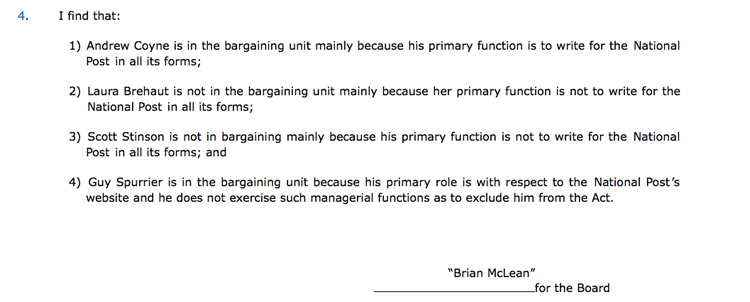

The vote was taken on September 29, 2017. Following a prolonged dispute at the labour board over a number of contested ballots, the effort officially failed by a single vote on April 26, after the board decided that two of the seven people that management wanted to include in the union should indeed have their ballots counted. Disputes over ballots are not uncommon in such situations, as both management and unions have an interest in seeing workers they expect to vote in their favour included in the final tally, and in excluding those they expect to vote otherwise. (Only those workers who would be represented by the union get to have their ballots count. In this case, that meant non-managerial newsroom employees of the National Post.)

O’Hanlon says the ruling was more or less par for the course at a labour board that can make snap decisions with little explanation. “You never know how it’s going to go. We knew it was going to be very close, we knew it would be down to one or two votes. So unfortunately, it went the other way.”

“I think a lot of people are just glad it’s over,” says one former reporter. She says she was uncertain how much a union would have improved things if it had succeeded but felt that management had effectively worked the situation to achieve its desired end.

“I think they played it well, unfortunately.”

Tannara Yelland is a member of the Canadian Media Guild, a local of CWA Canada, and previously helped start the CMG organizing drive at Vice Canada.

Email sent to the National Post newsroom in late September by editor-in-chief Anne Marie Owens:

Note from AMO

When I came back to the Post three years ago, I felt like the luckiest person in the world. As most who have left the Post will tell you — whether they left a decade ago or two weeks ago — the Post will always be the best place you’ll ever work. Hands down.

I’ve been thinking about that a lot the past few weeks.

What is it that makes the Post such a great place to work, and a place that for nearly two decades has held that title?

From its inception nearly 19 years ago, the Post has always been a great meritocracy. Amid a bland and predictable journalistic landscape where seniority and paying-your-dues determined all, the Post delivered the best assignment to whomever was best suited to the job. Thirty years in journalism and the contacts to prove it? The assignment is yours. Two years in but write like a dream? The assignment is yours.

That ethos was infused into the paper by its founding editors and persists to this day. Newsroom veterans have it in their DNA and impart it to each successive generation of Posties.

So much of what makes the Post unique is tied to the creativity that comes from a newsroom operating without a rulebook. The spontaneity and irreverence that defines the Post springs from journalists who are able to seamlessly shift between platforms and roles and departments. The culture remains dynamic because it values innovation and ideas above all else.

None of this should be taken for granted. That culture is why most of us are here.

We have always benefited from this approach, but never so much as today, when our industry is under stress, and we’ve seen a number of our competitors forced to lose the most promising young members of their staff. We’ve gained many of those talented journalists — often directed to us by their editors, devastated because they have no choice but to let go these rising stars.

We all want to keep working with the best and brightest in this business based on their talent, hard work and creativity — whether they’re a Day Oner or joined us a month ago. Preserving the Post’s culture is essential to our success, but more importantly, it is the key ingredient that makes this place special.

AMO