Read our follow-up to this piece here.

True, north, strong and free, Canada is worse at releasing public information than Mexico, Russia or Nigeria. We’re ranked 59 out of 102 countries, according to global access-to-information ratings by the Centre for Law and Democracy. Only two points separate Canada from Afghanistan.

We’re so bad at this that even governments within Canada are ranked higher.

If Newfoundland and Labrador was its own country, it would be 15th in the world for the right to information. Thanks to sweeping reforms the province passed back in June, Newfoundland is now one of the strongest global examples of access to information.

A lot of that can be traced back to Steve Kent’s childhood.

Kent is currently Deputy Premier with the province’s Progressive Conservative government, and was the Public Engagement minister who oversaw the recent overhaul of Newfoundland’s Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act.

He’s also adopted. Fourteen years ago, Kent applied for access to records in his adoption and child welfare file. He wanted to know his own past; where he had been in foster care, and who had been there with him. Instead, he ended up fighting the province for several years to ultimately end up with only a small portion of his own records.

“It was really about piecing together some of my own history,” Kent said. “Which, obviously, an individual should have the right to do.”

When reporters talk about ATIP problems, we’re usually speaking from personal experience. We’re self-centered like that. Navigating Canada’s obfuscated ATIP bureaucracy isn’t an immediate problem for most of the public, but it’s a daily challenge for journalists. But access to information goes beyond the media. This is a matter of national importance that Canada is utterly failing at, and it affects everyone right down to one Newfoundlander’s adoption.

“I know firsthand that access is important to individual citizens as well,” said Kent. “My own real life experience has helped me look at it through a unique lens, I guess.”

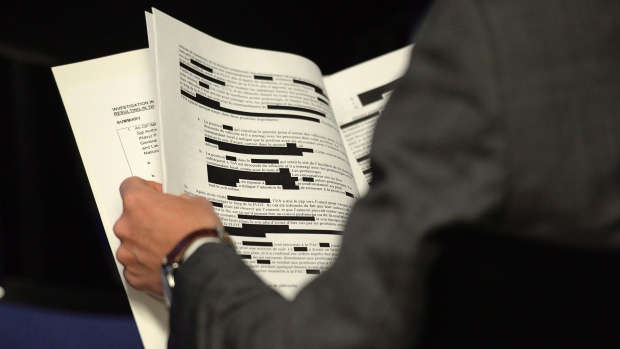

Every reporter has a horror story about a FOIPOP or ATIP request gone to hell. Months, if not years, waiting for a reply and exorbitant processing fees all to end up with a bundle of heavily-redacted pages. A recent audit by Newspapers Canada said the country’s access-to-information law is “effectively crippled.” Environment Canada, for example, took two months to release a list of the department’s Twitter accounts.

Why is Canada so bad at this? Partially, because we were so quick to adopt modern ATIP legislation. The Access to Information Act came into force in 1983. We were the 11th nation in the world to enact modern right-to-information laws. The standards and the world has since moved on, but Canada hasn’t.

“It’s great that we were an early adopter, but you then have to keep pace as the world moves forward,” said Michael Karanicolas, a senior legal officer for the Halifax-based Centre for Law and Democracy. The Centre works all over the world helping to draft access-to-information legislation and protect freedom of speech. They regularly update their global Right to Information Ranking, which scores 102 countries on 61 indicators broken down into seven categories. It’s that scoring system that places a nationalized Newfoundland at 15th, and Canada at 59th.

“This is an important democratic indicator,” said Karanicolas. “If Canada was 59th on gender equality. If Canada was 59th on environmental protection. I mean, these are core issues and I think the public would be outraged about it and we should be outraged here.”

Given that the top 10 countries in the CLD’s ratings all adopted their legislation after 2000 (many within the last five years), Karanicolas said Canada’s antique ATIP system is long overdue for an overhaul. There are too many exceptions, too many loopholes for non-disclosure and too many overly broad definitions for the Access to Information Act to be effective.

Compare and contrast with what’s happened in Newfoundland and Labrador. The newly passed ATIPPA legislation eliminated applcation fees and drastically reduced costs for access requests. Time frames shrunk from 30 calendar days to 20 business days and all readily available records need to be released in 10 business days.

The new law also expanded the powers of the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner. Extensions can now only be applied if the Commissioner believes them to be reasonably required. All formal appeals have to be dealt with in 65 business days, and should the public body disagree with the Commissioner’s recommendations it must seek a declaration from the courts stating that it is not required to comply.

The new regulations haven’t made everyone comfortable. Politicians know very well the challenges that come with more accountability, more access to information. Stronger legislation means you’re more likely to be caught, and more ammunition for your opponents.

“It is against their interests to have strong transparency laws,” said Karanicolas. “You see political parties promising the world, promising to enact this stuff…when they’re campaigning, and then completely forgetting that promise when they get into office.”

With that said, Karanicolas and Kent are both optimistic about the new federal government’s promises. The Liberals’ campaign platform pledged to update ATIP standards in Canada, including eliminating all fees save the initial $5 filing charge and expanding the Act to apply to the Prime Minister’ and Ministers’ Offices. They also promised to undertake a full legislative review of the Act every five years.

Should all that actually happen, Justin Trudeau will be the first Prime Minister to update Canada’s Access to Information Act since it was enacted by his father’s government.

On a smaller scale, Newfoundland’s example could pressure other provinces to reform their own legislation. Steve Kent hopes it will. He’s committed to open government, having experienced the opposite firsthand while trying to unearth his past. Closure isn’t the right word for the result of that endeavor, he said, but he did find some answers. It just “shouldn’t have been a battle.”

The Deputy Premier is now dealing with fights beyond his adoption records. He’s currently facing Liberal challenger Randy Simms for the Mount Pearl North riding in Newfoundland and Labrador’s November 30 election.

Win or lose, Kent’s helped ensure a more open and accountable government for every Newfoundlander. Now the rest of Canada just needs to catch up.

“The good and the bad and the ugly; regardless the public has a right to know,” he said. “All Canadians should have equal access, and all governments in our federation should be open by default.”