Canadian newsrooms are taking advantage of the job drought to make young people work long hours, handle heavy responsibilities, but deny them benefits for years. Federal and provincial employment laws do little keep anyone safe. What gives?

“This is not slave labour,” Randy Lennox, Bell Media president of broadcasting and content, told me. He turned to a room full of media students to continue his address, but I stumbled on the metaphor. It was fitting.

At a September information session for Bell Media’s new leadership program, the room was full of media students who collectively leaned forward, salivating at the mention of jobs. After a few minutes of patting themselves on the back, Bell Media executives, Lennox among them, took questions. I was second to speak.

“So we talked about Workplace Health as part of Bell Let’s Talk, but reality is that a lot of Bell Media newsrooms hire young people under ‘As Needed’ or three- to six-month contracts and these people work full-time hours with no benefits and no security for years,” I said. “So as a company looking to hire young people, what are you doing to improve their actual working situation?”

A few people fidgeted in their seats. Lennox took a second to consider. “Great question,” he said. “So, you’re saying that in the news area of Bell Media, specifically? That work for Bell? Or just work in general?”

“Nope, work for Bell.”

“OK, so we would never hire anyone with the intent of being part-time and make them work 60 hours a week, that would never be our intent, so I’ll start with that, because this is not slave labour,” he said. “What this is is balance. We’re a balanced company, particularly in light of the fact that Let’s Talk and mental health is very very important to us. And not just because we work there, it actually means something.”

I clarified: “I am talking about people who are on contract, and they are working full-time hours … they’re basically permanent freelancers, and for years they work without benefits or security.”

“The nature of news itself is intermittent,” Lennox replied. “In other words, news requires a heavier staff at times of heavy news and a lighter staff at other times. If your question is, why don’t we hire everybody full-time, there’s not a business model there. To employ thousands of people is very challenging so we have to go the freelancer route.

“But where we can, we hire someone full-time because of the substance of the job — that’s why we’re here, by the way.”

He didn’t seem to understand I wasn’t talking about freelancers, but full-time workers who are contracted as if they are freelancers.

These people aren’t taking on brief gigs, but show up for regularly scheduled hours. Yet their often short, often shitty contracts list them as freelancers. Or maybe he did understand, but avoided the question. It’s one of the most tabooed conversations in modern journalism, after all.

With dozens of newsrooms using loopholes to keep some staff on freelance contracts without benefits, this reality has become standard. Though it’s not clear how many Canadians are on these contracts, Statistics Canada reports that in the last two decades temporary work is on the rise.

In the ever-shrinking news industry, which has been bleeding money for years, this has blurred the line between “freelancer” and “employee.” Now, there’s a new class of employee: “permalancers.” As I learn more about this reality, I keep asking myself, ‘How is this legal?’

Legality seems like least of Lee Richardson’s concerns. Having cycled through the National Post, MSN, BNN and the Toronto Star (where he got health benefits for the first time, until the layoffs in August) since 2012, he’s familiar with the permalancer contracts, insecure employment, and dismissals that plague young journalists.

“I get why they’re doing it, but it’s like a whole industry is basically propped up on these people who are just interns — just paid interns,” Richardson told me.

Though he’s never had a contract shorter than 12 months, he also doesn’t usually comb through his agreements.

The eight young journalists I’ve spoken to for this piece said they feel grateful to have a job in the industry at all. They see questioning their contracts as being ungrateful. Most said they wouldn’t bring up issues with their employers for fear of burning bridges.

Richardson said a lot of people in journalism have to deal with the instability. “They’re all going through this, they’re all trying to get benefits because they haven’t been to the dentist in years, or they’re … thinking about buying a condo and they’re like, ‘Well, is my job going to be there in six months’ time?’”

To get to the bottom of how these contracts mesh with government regulations, I spoke to Don Genova, the Canadian Media Guild organizer for freelance workers.

In a unionized place like the CBC, Genova explained, temporary workers who replace absent employees are paid the same base rate as regular employees. Thanks to the collective agreement, if they are hired on a contract longer than 13 weeks, they are also automatically enrolled in the medical plan. These rules don’t apply in non-unionized newsrooms.

Genova said these contracts are “a way of keeping the workforce disposable.”

While the law doesn’t prevent short-term contracts, there are standard protections for employees. The rules differ between federally regulated employers like CBC and other TV channels, or provincially regulated workplaces like print and online outlets. The distinction defines which rules apply: the federal Canada Labour Code or provincial employment laws like Ontario’s Employment Standards Act.

“But they don’t provide any restriction from the contract itself,” explained Arleen Huggins, an expert in employment law and a partner at the Toronto-based law firm Koskie Minsky.

“Oftentimes in these types of contracts, the employer tries to say [workers] are not employees. That the individuals are contractors. But the Employment Standards Act takes a very wide view of who is an employee. For the most part if it looks like a duck, it’s a duck, no matter what you call it.”

Short-term contracts are most often used by employers to keep employees from “acquiring service,” Huggins said, “As though the employee’s being hired fresh each time.”

This would make it easier to bypass minimum standards like probationary periods, termination notices, statutory severance pay, or pay in lieu of termination notice.

“When you have four or five contracts that are continuing for three months each, it looks like a duck,” she said. If employers only take the last of several consecutive contracts into account (in calculating, for example, notice for termination) courts tend to side with the employee.

But the problem is that many workers don’t know or fight for their rights, Huggins said. “Many employees wouldn’t know anything about what I’ve just spoken to you about.”

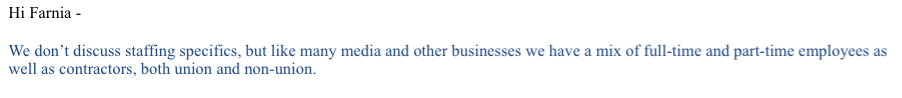

I emailed Bell Media six detailed questions about freelancers and contract workers. I also wanted to know how these contacts mesh with their mental health initiative. This was their full response:

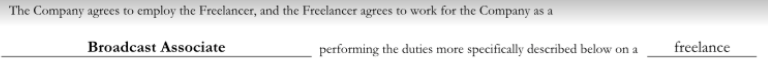

I spoke to a Bell Media employee, who asked to stay anonymous for fear of repercussion, about her current contract. Having started on a three-month agreement, she has worked for almost two years in one of the company’s many newsrooms as a permalancer. She’s not technically self-employed, given that both she and her employer pay EI and CPP.

She said she doesn’t know the details of her current contract.

“It might not be the fact that it’s my employer’s fault, it might be that I was just so excited to get a job, that I didn’t even care to look,” she said. “I honestly don’t ask questions … and I don’t want to piss anyone off. This is a massive, massive company that has so many different streams of television. You want to kind of make these people happy.”

She thinks the turnover rate at Bell is high enough to make her easily replaceable.

“It doesn’t matter how good of an employee you are … someone else is right behind you,” she said. “If someone came to my role and said, ‘I want benefits, I want health care, all these things,’ they would laugh and then give the job to someone like me.

“The most depressing part of it is that we think this is a great thing. I honestly don’t think they’re trying to be malicious,” she said. “I think it’s just been done for so long.”

***