“Providing a public and privileged platform for individual voices — in the pages of Toronto’s biggest daily, no less — is a journalistic trust held dear at The Star. This despite the fact all the usual reporting rules — objectivity, balance, the writer staying out of the way of the story — are turned on their head, a critical distinction of column writing that many readers continue to misunderstand.” — Rosie DiManno, reflecting on the role of the Toronto Star’s columnists at the time of the paper’s 110th anniversary, November 6, 2002

For much of its existence, the Toronto Star has touted the “Atkinson Principles” as its guiding light for editorial policy. Among its points are support for social justice, individual and civil liberties, and community and civic engagement. Like many columnists the Star has showcased over the past 125 years, Desmond Cole’s work fits within these contours.

But Cole’s columns on Black matters and policing made some Star executives uneasy. In June 2016, his column went from weekly to biweekly. In the aftermath of his protest at a Toronto Police Services Board meeting in April, Cole gave up his column, and public editor Kathy English admonished him in a piece entitled “Journalists shouldn’t become the news.”

This is not something the Star has taken issue with in the past.

Immediate responses on social media highlighted other recent Star columnists, such as Catherine Porter and the Kielburger brothers, whose activism wasn’t muted while working for the paper, even when they became stories. The paper’s support of writers like Daniel Dale, when he became the news thanks to his run-ins with Rob Ford, also arose.

But activism is embedded in the Star’s DNA, and its original employees made headlines.

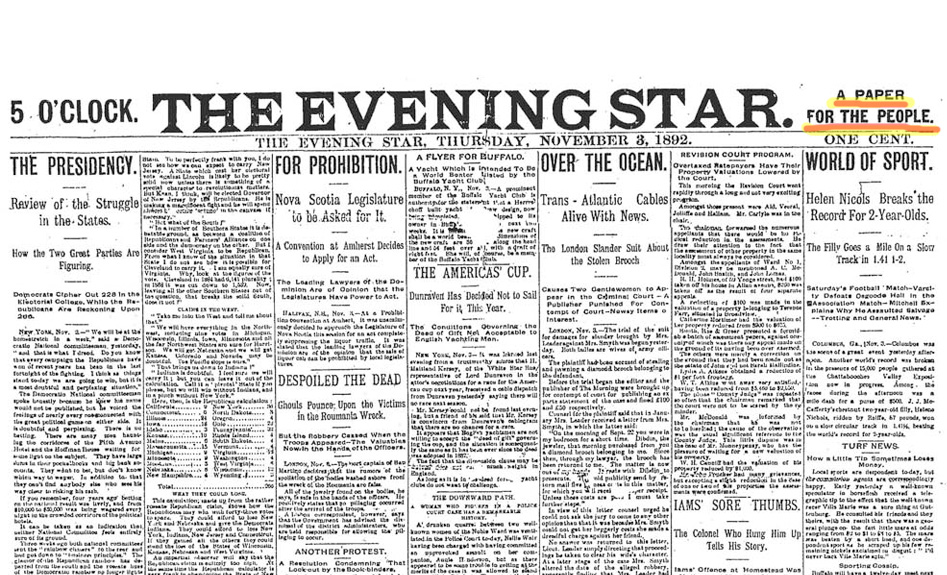

The paper began as a result of labour activism, when 21 unionized printers and four apprentices were locked out by the Toronto Evening News in October 1892.

The dispute arose when the News introduced a new typesetting machine that allowed one printer to do the work of three men. The Toronto Typographical Union agreed to drop its opposition to the new technology, on the condition that only union members would operate the machines and that any savings would be passed on to employees. But how much to pay the printers under this arrangement became a stumbling block. As assistant foreman Harry Parr put it, there was “a mutual agreement that we could not get along together.”

On October 24, the printers voted to strike if their demands weren’t met. The next morning, their dismissals were nailed to the door of the News.

When it became clear that strike pay wasn’t enough for them to live on, the locked-out workers adopted an old tactic: they launched their own newspaper. Unlike other such papers, which only lasted as long as the disputes that inspired them, the founding staff of the Star vowed to run an ongoing newspaper dedicated to serving the needs of workers. Or, as the paper’s original slogan proclaimed: “A Paper for the People.”

Printers converted themselves into reporters. Several members of the original staff became local movers and shakers, with two (Horatio Hocken and Jimmie Simpson) eventually serving as mayors of Toronto.

But the paper struggled in the face of six daily competitors, and while most of the strikers drifted back to the News within a few weeks, a core of diehards — whose militancy decreased their chances of working elsewhere — stayed on. The paper limped along, enduring several owners and one extended hiatus, until Joseph Atkinson arrived in 1899 and began to shape it into the Star we know today.

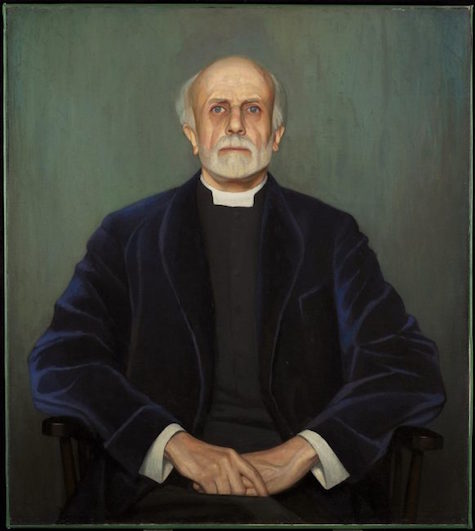

One of the first activist columnists the paper employed was the Reverend Salem Bland, who began writing for the editorial page as “The Observer” in 1924. Possibly best known today as the subject of a Lawren Harris painting, Bland was a Methodist minister who, as The Canadian Encyclopedia puts it, “mixed temperance, Sabbath observance, and church-union advocacy with moderately socialist views.” The latter periodically got Bland into trouble with church donors and congregations.

Bland’s columns were labelled “dangerously inflammable” during the 1930s; the Star’s bitter conservative rival, the Telegram, called him a Communist. But his political activism was not affected by these catcalls, as Bland played a role in the formation of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (which later became the NDP). Bland wrote for the Star until his death in 1950 at the age of 90.

One of the paper’s most opinionated writers during the mid-20th century was Gordon Sinclair, whose inflammatory writing style cost the paper $120,000 in lost libel suits. It was claimed he was fired by the paper 11 times, but quickly brought back every time.

By the 1950s, despite being busy with daily radio commentaries on CFRB (the same station on which Cole currently hosts a show) and sitting on the panel of CBC TV’s Front Page Challenge, Sinclair still had time to write a regular radio/TV column for the paper. But only rarely did one of Sinclair’s pet crusades cross into the column: his war against water fluoridation. In public debates, Sinclair butted heads with medical officials, always referring to fluoride as a poison.

While the paper kept Sinclair on as a columnist through 1962, his fellow Star writers poked fun at his passion. For example, in a 1959 column, Pierre Berton pondered what one of Sinclair’s frequent sparring partners, Health League of Canada founder Dr. Gordon Bates, would say if Sinclair suddenly died from an overdose of sodium fluoride:

“The sudden death of Gord Sinclair is an irreparable loss to the opponents of fluoridation of city water supplies, and they have my deep and heartfelt sympathy. Although Mr. Sinclair and I did not always agree, there was no doubt in my mind that his misguided views were sincerely held. He brought to journalism that dash of ‘colour’ so sadly lacking on the Canadian scene and this together with his intense love of family and his fearlessness in espousing lost causes, endeared him to all who knew him.”

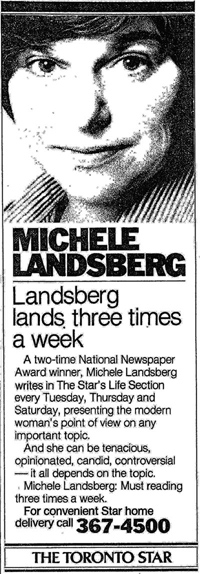

The front page of the May 15, 1978, edition of the Star touted the arrival of a new daily Family section columnist: Michele Landsberg, who was billed as “flamboyant, refreshing, opinionated.” Over the next quarter-century, she tackled a wide range of feminist topics.

“Feminism,” she wrote in 2003, “embraced everything in a woman’s self-determining life, from chicken soup recipes to the Nestlé boycott to fighting like a banshee to save female refugees from being deported back to murderous husbands or governments.”

Landsberg’s advocacy of women’s and children’s rights, and tackling of issues such as abortion and racism, was backed by the paper. Her presence at picket lines and protests was tolerated, and, as she recounted in a recent piece for NOW, her editor printed a petition when Landsberg tried to prevent the closure of a childcare centre. When the Morgentaler Clinic was bombed in 1983, one of the most visible bits of debris at the Toronto Women’s Bookstore below was a copy of her book Women and Children First.

Landsberg’s final Star column in November 2003 was surrounded by a four-page tribute leading off the Life section. Her final sentence urged readers to elect David Miller as mayor in the upcoming municipal election instead of sending flowers.

When Landsberg and her husband Stephen Lewis moved to New York City in the 1980s (and Landsberg moved over to the Globe and Mail for a time), her replacement was an icon of Canadian feminist journalism. Doris Anderson was touted upon her arrival at the Star in 1984 as bringing “a reputation as a fighter for social justice.” Her long list of accomplishments was trotted out: editor of Chatelaine for two decades, where she transformed the magazine into a forum for women’s issues; chair of the Canadian Advisory Council on the Status of Women; and president of the National Action Committee on the Status of Women, where the end of her term briefly overlapped with her Star duties.

Anderson’s column ran for a decade, and she enjoyed, as she observed in her autobiography Rebel Daughter, “the scope I was given to write about anything from politics to pop art.”

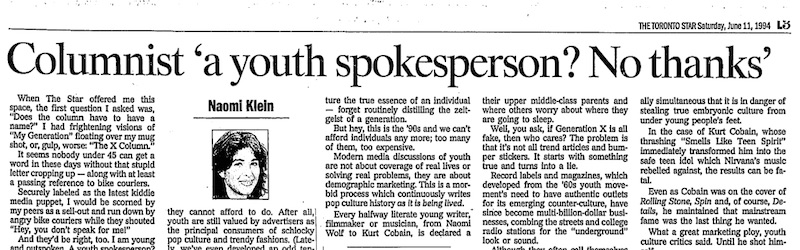

Soon after Anderson’s time at the Star wound down, Naomi Klein received a weekly media and pop culture column. In her June 11, 1994, debut, Klein took shots at the marketing and perceptions toward labelling her age bracket as Gen X. “Young people have enough pseudo spokespeople these days,” Klein wrote. “What they really need is the space to speak for themselves, a space that is more interested in looking squarely at diversity — economic, religious, ethnic, you name it — than in muffling it with slogans and generalizations.”

Two years later, Klein’s column moved to the opinion page, the same week as Andrew Coyne moved over to the Star from the Globe. Publisher John Honderich praised both columnists for being “superb young writers, with divergent perspectives; their presence will make the Opinion Page crackle with new ideas and make it that much livelier.” Klein’s columns took on more social and anti-corporate issues, and she remained with the paper until a few months before the release of No Logo in 1999.

In her NOW piece, Landsberg observed that while neutrality is important for reporters, columnists are valued for their opinions, especially if they run contrary to the mainstream. “When a columnist is also an activist,” she noted, “he or she brings not only insider knowledge of a community, but brings that community to the paper.”

While the Star has embraced communities from strikers to feminists, its seeming rejection of the marginalized community Cole represents is troubling. In the wake of the furor, the Star published pieces by Azeezah Kanji and Shree Paradkar (the latter of whom has since been made a full-time columnist) questioning the paper’s moves with regard to Cole.

“I’m sad to think,” Landsberg concluded, “that the newspaper I cherished as a home for progressive voices might be crumpling into bland and craven conformity.”

Top image of the first edition of the Toronto Star, proclaiming itself “A Paper for the People” (highlighting ours).