In December 2019, the CBC fired reporter Ahmar Khan after learning he’d been Canadaland’s confidential source for a story. They discovered this after a colleague went through Khan’s personal social media accounts — that he’d left logged in on a shared computer — and turned over evidence to a manager, who then went through the accounts herself.

Khan’s union, the Canadian Media Guild, grieved the dismissal, and this week an arbitrator ruled the CBC acted improperly in firing him, ordering the public broadcaster to offer him reinstatement for the four remaining months of his contract, or, should Khan decline that, to simply pay him out the four months’ salary.

The employer’s stated grounds for termination, wrote arbitrator Lorne Slotnick, were “far overshadowed by the breach of his privacy that enabled the employer to discover those activities.” He also concluded that Khan is entitled to damages for the breach, in an amount to be determined.

The entire ruling is worth reading, navigating such tricky subjects as objectivity in journalism, systemic racism at the CBC, and whether it ought to be a fireable offence to refer to one’s boss (in private conversation with a third party) as an “asshole.” Slotnick himself was formerly a reporter, covering labour for the Globe in the 1980s.

But let us summarize the highlights.

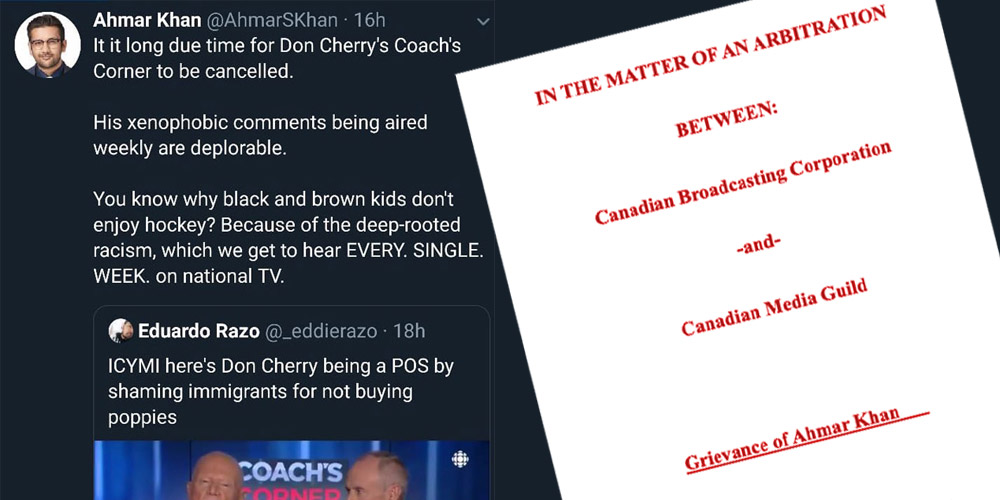

On November 9, 2019, Khan posted a tweet calling out remarks that Don Cherry made on what turned out to be his final episode of Coach’s Corner.

“It [is] long due time for Don Cherry’s Coach’s Corner to be cancelled,” tweeted Khan, then a reporter/editor at CBC Manitoba. “His xenophobic comments being aired weekly are deplorable. You know why black and brown kids don’t enjoy hockey? Because of the deep-rooted racism, which we get to hear EVERY SINGLE WEEK on national TV.”

Though hardly a unique sentiment on Twitter that weekend, Khan’s observation went particularly viral, perhaps in part because it came from a user with a CBC email address in his bio.

It came to the attention of Melanie Verhaeghe, managing editor at CBC Manitoba, who believed it ran afoul of the CBC’s Journalistic Standards and Practices (JSP), which bar journalists from expressing “personal opinions on controversial subjects, including politics,” on social media.

What happened next, per the ruling:

Ms. Verhaeghe wrote by email to Paul Hambleton, the person in charge of the journalism standards policy, asking for his opinion, saying that Mr. Khan had said his job is to call out racism, and “this isn’t the first employee of colour to feel this way and not only about Don Cherry.” Mr. Hambleton responded that it was a clear violation of policy, that if Mr. Khan “wants to be an activist he should step down. Everyone hears what they want to hear from don cherry.” Ms. Verhaeghe then had [assignment producer Jill] Taylor write to Mr. Khan asking him to delete the tweet, because it violated the social media policy. Ms. Taylor included in her email the relevant portion of the Journalistic Standards and Practices, and added that he would not be assigned to cover this topic, “as you have shown the audience your bias. In the future, I suggest you pitch a story about it instead of reacting online – you will reach a wider audience this way.”

Khan grudgingly deleted the tweet after speaking to Bertram Schneider, the executive producer in the Winnipeg newsroom, who, Khan said at the arbitration hearing, had previously told him to take down a tweet that encouraged reporters to ask Andrew Scheer why he neglected to mention Islamophobia in a statement following the Christchurch mosque massacre.

Unhappy with what he saw as the CBC’s selective enforcement of the JSP in a way that disproportionately affected employees of colour, Khan reached out to Canadaland to let us know what had happened, asking not to be named as our source.

He also got in touch with Maclean’s columnist Andray Domise, whom he described as “a friend and mentor,” and gave his blessing to a tweet about the situation.

At the time, a CBC spokesperson quickly confirmed to Canadaland that the corporation had asked Khan to remove the tweet on account of the JSP, and we published a story on the morning of November 14.

“Mr. Khan testified that even though he was conflicted about telling Canadaland about the issue,” Slotnick wrote, “he felt a discussion was necessary about race and the CBC and about how the CBC’s journalism policies were silencing employees of colour. He said he believed the Canadaland piece sparked discussion within the CBC.”

Nearly two weeks later, Khan signed out a company laptop for use on a story but failed to log out of his Twitter and WhatsApp accounts when he brought it back to the office and left it on his desk.

On Nov. 28, Austin Grabish, a fellow reporter who had evidently taken the laptop from Mr. Khan’s desk, notified Ms. Verhaeghe that he had found some unethical material on the laptop. Ms. Verhaeghe testified that Mr. Grabish described the contact with Canadaland and said the material was visible to him because the programs were open when he got the laptop. Ms. Verhaeghe said Mr. Grabish directed her to messages in which Mr. Khan told a friend he had contacted Canadaland, and also to the exchange with Mr. Domise.

Screenshots of various messages were put into evidence. It appears that Ms. Verhaeghe took some of the screenshots, and Mr. Grabish sent her others. Ms. Verhaeghe testified she verified that the screenshots Mr. Grabish sent were on the computer, by searching Mr. Khan’s open Twitter and WhatsApp accounts. She said privacy was not the main concern because the consensus when she consulted the human resources department and her boss was that she had no choice but to confirm the material that was already sent to her, and because there should be no expectation of privacy on a shared laptop. She said she did not discuss any privacy concerns with Mr. Grabish, nor did she ask him whether he had to search to find some of the messages.

However, it appears clear from the screenshots that one of the shots of a WhatApp screen that was sent by Mr. Grabish came up because of a search of the word “tweet.” One screenshot where the date on the computer screen was Monday did not have a WhatsApp tab opened in the browser, while another screenshot taken on Tuesday had a WhatsApp tab opened, suggesting that someone had opened an inactive WhatsApp account when it had not been open.

Neither party called Grabish, a bargaining-unit member, to testify at the hearing. He did not respond to Canadaland’s request for comment prior to the initial publication of this article but later shared a statement, which we’ve included below in an update.

A further screenshot showed Khan complaining to a friend about the enforcement of CBC policies: “The trouble with the motherfucking JSP is that it’s easy to say use the union when you’re a permanent employee, that is not the case for me. this assholes say ‘this is the second time’ I’ve done this. The other time was when Andrew Scheer ‘forgot’ to acknowledge Islam in his Christchurch massacre.”

“There was also,” Slotnick wrote, “a WhatsApp exchange between Mr. Khan and 10 of his friends with what could charitably be described as nonsense banter, in which Mr. Khan used the phrases ‘fAWKING FAGGG YO’ and ‘WHAT A FAG YOOOOo,’ among a group of other messages that would unlikely be understood by anyone except by that group of friends.”

Khan testified that those messages, which predated his employment at the CBC, were part of a joke in which he and his pals were “mocking the patter of thugs from Surrey, B.C., and Brampton.”

In yet another screenshot that Grabish shared with his manager, Khan seemed to be commenting to friends about Verhaeghe’s appearance. At the hearing, however, Verhaeghe was shown the message in its original context, which revealed that the remarks (“told he she looks real nice in desi clothes”; “she got hype”) appeared to concern a different person altogether, whose photo had appeared just above in the thread.

The CBC fired Khan a few days later, citing his contact with other outlets about the Cherry tweet, the disparaging comments about CBC management and policies, and the use of a homophobic slur on WhatsApp, where his avatar had depicted him wearing a CBC jacket.

But “while she had concerns about homophobic slurs and comments about her, Ms. Verhaeghe said, the main problem was that Mr. Khan was trying to drum up disparaging stories about the CBC in other news media outlets when his concerns should have been discussed with CBC management.”

This was echoed by the CBC, whose arguments in the arbitration proceeding strongly hit on the theme of reputational damage, according to the decision:

The CBC emphasizes that Mr. Khan was not disciplined for tweeting about Don Cherry, nor was that one of the grounds for the termination of his employment a month later. The reason for his dismissal was his egregious conduct after he was told to take down the tweet. That conduct involved him going behind his employer’s back in a planned attempt to generate publicity and make the CBC look bad.

…

Mr. Khan’s conduct in contacting other news media was an attempt to undermine his employer’s reputation in the eyes of the public, the CBC says. His disdain for the CBC continued after the dismissal as indicated in tweets he has posted since then. He violated his duty of fidelity by placing his own feelings and interests ahead of those of his employer, and in the process harmed the employer’s reputation, the CBC says.

…

…the dismissal is first and foremost about his contacts with external news media outlets. A reasonable and fair-minded member of the public, apprised of the facts, would conclude that Mr. Khan’s continued employment would damage the reputation of the employer, the CBC argues.

The union countered that not only was there no evidence that the CBC’s reputation was harmed but that Khan’s actions were in fact a call for the precise kind of public discussion that CBC News management trumpeted months later, when, in the context of worldwide antiracism protests, they announced a review of the JSP, with an eye toward its potential to muzzle journalists of colour.

Also, “referring to management as ‘assholes’ is so common that there would be few people still working if that were grounds for termination, the union says.”

Slotnick ruled that despite using a shared work computer, Khan had a reasonable expectation of privacy, in that he couldn’t have reasonably guessed that a co-worker would “comb through” his private social-media messages rather than simply logging him out.

The arbitrator also took a dim view of CBC management following up on Grabish’s tip by going on their own expedition through his messaging history.

“Even if the employer had a legitimate concern resulting from what Mr. Grabish told Ms. Verhaeghe,” he wrote, “it appears that no consideration was given to the scope of the search or the use of a less intrusive manner of investigation, such as asking Mr. Khan about the situation. If the main concern was that Mr. Khan had been the source of the information for the Canadaland story, it is not clear why Ms. Verhaeghe was looking at messages from Mr. Khan to his friends from 10 months prior, or why she could not simply have started by asking Mr. Khan about the provenance of the Canadaland story.”

But Slotnick found that even if the privacy violation hadn’t “tainted” the entire process of Khan’s dismissal, the stated reasons for it were nevertheless wanting.

The homophobic slur, in the context of “nonsensical” messages among friends, both predated and had nothing to do with Khan’s job. With regard to a private reference to his supervisors as “assholes,” Slotnick agreed that “if employees could lose their jobs for privately criticizing their bosses – even if in crude terms – this country would be facing a severe labour shortage.”

And as to the leak:

…Many people might find it ironic, even amusing, that a news organization that, as with any other major news outlet, is alerted to significant stories by sources who are granted anonymity, would be surprised and indignant that one of its own employees used the same technique to give a story about the CBC to another news outlet. I am one of those people. Mr. Khan thought Canadaland, which covers events in the news media, would be interested, and he was right. What is notable about Mr. Khan’s messages to Canadaland and to Mr. Domise telling them about the order to delete the tweet is that they set out the facts of the situation accurately and without exaggeration. While they criticize CBC policies and their application, they do not disparage the employer or any of its managers.

…

CBC employees have been known to speak out publicly about CBC-related issues – as many have recently, for example, regarding the CBC’s “branded content” initiative, called Tandem – without fearing discipline for sullying the CBC’s reputation.

Moreover, the subsequent blowup about systemic racism at the CBC “cast light on the reasonableness” of the discipline, given that his complaint about the mandated tweet deletion became a part of that discussion.

“How, then, can that complaint, expressed in the only way he felt would not doom his chances for a permanent job, be serious enough misconduct to warrant dismissal?”

In a single-word missive Wednesday evening in response to the ruling, Khan offered this thoughts:

Vindicated.

— Ahmar Khan (@AhmarSKhan) January 14, 2021

Update (January 14, 2021, 9:56 p.m. EST): On Thursday afternoon, Grabish shared a statement with Canadaland, which he also published to Twitter, saying he was disappointed to have not been asked to testify at the hearing “or given an opportunity to present the facts.”

He asserted that when he opened a laptop that he’d left on his desk after using it “for months,” he saw an unfamiliar WhatsApp screen that he then opened.

“I was shocked and disappointed,” he said, “to see both a thread of misinformation about the CBC and several homophobic messages including a photo of two men with the words ‘JUST A COUPLA FAGS.’ As a gay man, I know what it’s like to be marginalized and grew up repeatedly being the subject of regular homophobic slurs and bullying because of my sexual orientation. I was disappointed and hurt by what I found and reported it to my senior manager.”

Grabish has not yet responded to Canadaland’s request to clarify the nature of the “misinformation” and whether he was suggesting that when he opened the laptop in November 2019, its screen was displaying the same WhatsApp conversation that the arbitrator said dated to more than a year earlier.

In his statement, Grabish said he had “very clear professional obligations under CBC’s code of conduct.

“My union has since emphasized to me that I could have been disciplined for not bringing that information forward. With this in mind, I am alarmed the Canadian Media Guild has not supported me further.”

“I have no knowledge of anyone in our union advising our members they could be disciplined for not disclosing information to management,” Kim Trynacity, the president of the guild’s CBC branch, tells Canadaland in an email, noting that the union has “provided representation to all CMG members involved when asked, as is our legal duty, and will continue to do so in future.”

(Asked about the professional obligations to which Grabish may have been referring, CBC spokesperson Chuck Thompson shared an excerpt from the code of conduct: “It is important to speak up if you observe or experience inappropriate behaviour. You are strongly encouraged to immediately notify your manager of any possible breach of this Code.”)

Trynacity says that at no point did the union publicize Grabish’s identity and that it was the CBC that disclosed it as part of the evidence it presented to the arbitrator, without requesting it be kept confidential.

“But let’s be clear in all this: the victim in this case was the young BIPOC journalist whose privacy was violated and who was wrongly dismissed,” she says.

In a statement on its website, the union said the CBC informed them that it’s “reviewing the ruling, and has not yet determined if it will seek a judicial review.”

Canadaland employees are members of CWA Canada, of which the Canadian Media Guild is a local.