The Globe and Mail’s hire last month of James Griffiths as their new China-based Asia correspondent drew a snarky tweet from former Globe reporter Jan Wong, who worked the same job years ago.

Wong’s remark comes at a time when there has been renewed scrutiny over newsroom diversity and opportunities for journalists of colour. But the conversation often skips over foreign reporting, which arguably touches on more lives of people of colour than other journalistic areas.

Hey @globeandmail It’s 2021! In the 62 years since 1959 when you opened 1st Beijing bureau of any Western paper, I have been the only woman & only non-white correspondent. https://t.co/AjHSlRc5rp

— Jan Wong (@WriterWong) June 11, 2021

Wong’s retort also comes at a time when Canadian media’s foreign-reporting rosters have shrunk thanks to financial struggles and other pressures of the digital era.

Online news and social media allow users to easily access information and news about other countries without relying solely on foreign correspondents hailing from their own countries.

The few who do report overseas are often not journalists (of colour) with the cultural backgrounds, language skills, and connections needed to access local stories that satisfy a diverse Canadian audience. Addressing this perennial issue gets tougher as outlets face today’s financial and structural issues.

Still, several major Canadian outlets have retained foreign bureaus and correspondents, but the focus is on the Western world.

The CBC currently has a total of 12 main foreign correspondents spread across the U.S., UK, Russia, and a new upcoming bureau in India. Another, Saša Petricic, was covering Asia out of Beijing before the pandemic.

According to Greg Reaume, the CBC’s managing editor for world news coverage, the public broadcaster is “contemplating other locations for a Far East correspondent” after Petricic was repatriated. The Chinese government, Reaume said, hasn’t granted any new visas to any CBC correspondents since the pandemic began last spring.

Reaume added that the CBC had “recently streamlined the managerial/supervisory structure around our international operations allowing us to add another full-time correspondent in Washington.”

This latest correspondent was just named as Makda Ghebreslassie, the child of Eritrean parents who, according to a CBC release, has “won praise for her ability to reach into communities and make connections.”

Among Canadian outlets, the CBC has the largest foreign-reporting roster, with 12, and the most journalists of colour on that roster, at four.

The Globe and Mail has seven foreign correspondents spread across the U.S., UK, Italy, South Africa, and China. CTV has five correspondents in the U.S. and UK. Global News has three in Washington, DC, and two in London, England, while the Canadian Press and the Toronto Star each has one correspondent in Washington.

This adds up to 32 foreign correspondents between six major news organizations. Seven out of these 32 are journalists of colour; five of these seven are women. In total, over one in five foreign correspondents among this total of six major Canadian news organizations are journalists of colour covering the world through Canadian eyes.

“I think, anecdotally at least, these numbers are actually an improvement from an era where it’d be very rare to have journalists of colour in foreign-correspondent positions, since representation wasn’t great in newsrooms anyway,” said Sonya Fatah, a former special overseas correspondent for several Canadian newspapers who now teaches at the School of Journalism at (what is at least for now called) Ryerson University in Toronto.

“Canada has this rich potential because it’s home to so many people who have connections around the world, but we’ve never tapped into that,” she added. “Instead, almost all news agencies, not just Canadian ones, station their foreign correspondents in the cities of major global powers.”

Among Canadian foreign bureaus, there’s a heavier focus on the United States and Europe, which tend to be covered by more correspondents, be it in Washington, New York, or London.

The CBC has five journalists at their DC bureau, along with one in New York and four in London. The Globe has five of their seven foreign correspondents in either the US or Europe. All of CTV and Global News’ foreign correspondents are also either in the US or UK.

Many other bureaus are also staffed by a single person, including the new CBC bureau to be opened this fall in Mumbai, India, staffed by former Parliamentary reporter Salimah Shivji. Same with the Globe’s bureau covering Africa, staffed by Geoffrey York in Johannesburg, South Africa, and its Asia bureau in Beijing.

The Toronto Star, which once had reporters stationed across the world, and the Canadian Press, have only one foreign bureau each, both in Washington, DC. Only one correspondent from each organization staffs these bureaus – Edward Keenan for the Star and James McCarten for CP.

“When I first landed in Canada, I thought, ‘Wow, this is absurd, this is a country with such diverse demographics, but they’ve got little interest in reporting from these places,’” said Fatah, who’s in her last month as the editor-in-chief of J-Source.

This dizzying diversity, she added, amounts to an untapped audience made up of diasporic communities that thirst for information and updates about the places they migrated from. But this dimension of Canada often doesn’t make up what editors imagine as the true “Canadian audience.”

“The foreign editor job is a really important one in terms of directing the kind of narratives that can emerge from different locations and not just resting on stereotypes or singular themes, but to challenge dominant narratives by digging deeper,” she said.

“If a foreign editor plays the role of encouraging their teams in various locations to go beyond the obvious, the publication can still pick up regular news from wire services but rely on their foreign reporters to do more unusual and interesting storytelling.”

The key, though, for reporters anywhere is that they must have real local access to the stories in the countries they’re posted in.

“It was rare to see journalists sent who actually had connections to the diaspora or to the history of the places they were sent to,” Fatah said. “And they would rely on local ‘fixers,’ who are most often just local journalists that got no recognition.”

She added that papers like The New York Times now give these local journalists shared bylines because they realize their importance, especially when the foreign correspondent first arrives at the posting and has no connections in the country. It’s these “fixers” — a rather inadequate term — who share all their sources and intelligence, only to get little-to-no recognition in the end.

But as Fatah noted, this entire dynamic is being challenged as newsrooms become more diverse and foreign reporting comes under severe financial strain.

“Traditionally, in Canadian media, foreign correspondence has been kind of like the prime thing that you get based on your skills, ability, what you’ve done domestically,” said Christopher Waddell, professor emeritus at Carleton University’s School of Journalism and Communications, who worked for the CBC and the Globe. “It’s kind of like a ladder you go up, from local news and national news, then international news.”

“If you put more new people out of journalism schools, which are becoming more diverse, in that pipeline, then ideally more of them will end up in foreign coverage,” he said. “The problem is that the ambitious young people who want to become foreign correspondents have fewer and fewer places to go, which makes it harder and harder to do.”

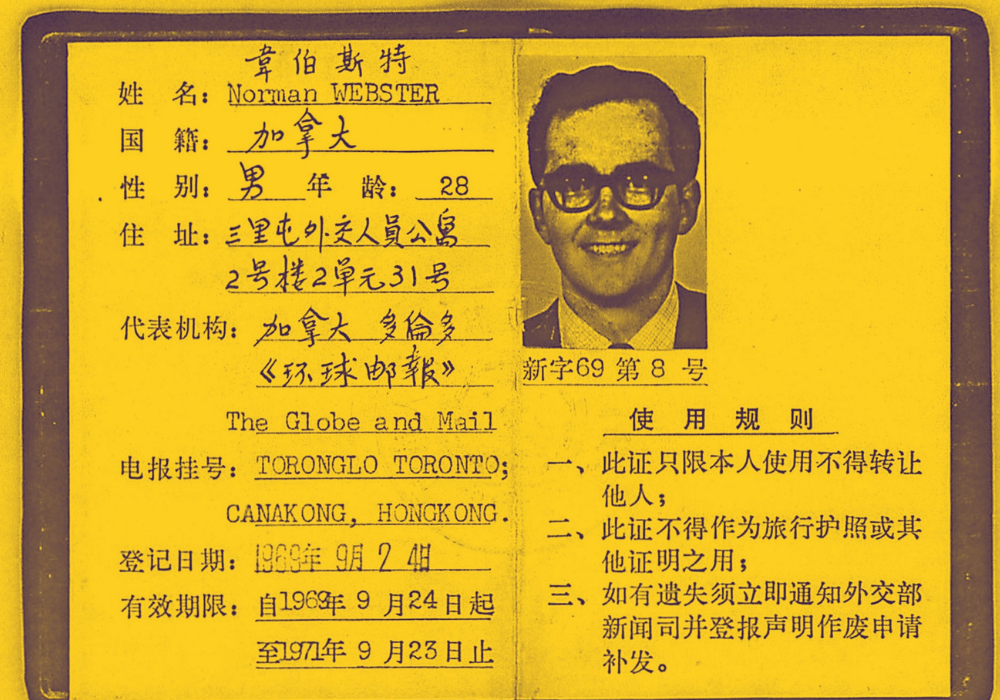

Top photo: Adapted from the original