On Friday, CANADALAND published a story headlined “How a Politician’s Childhood Helped Shape Freedom of Information Reform” and political geeks in Newfoundland and Labrador flipped out.

Individually, nearly every piece of information in reporter Jacob Boon’s story is correct.

Unfortunately, taken as a whole, the story is spectacularly wrong.

It’s true that Canada’s access to information system is godawful. It’s true that this year Newfoundland and Labrador enacted a law that is marvellous for journalists and anybody else looking for government information. It’s true that Deputy Premier Steve Kent, in recent years, has been responsible for the N.L. Office of Public Engagement, and in that role he has been one of the leading government voices pushing for a more open and transparent government. It’s also true that Kent is adopted.

But to tie Kent’s adoption to the N.L. government reforms to the Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act (ATIPPA) misses the real history, and for anybody interested in improving things elsewhere in Canada, the real political history may be instructive.

The bad old days

The current N.L. access to information regime is relatively young, proclaimed into law in 2005 under Progressive Conservative Premier Danny Williams.

And as often happens, the Tories grew to hate the obligations of the access to information system. Access to information responses were slow coming, heavily redacted and the government would play all sorts of games to hide embarrassing information.

In 2010, five years after the law first came into force, the government appointed a bureaucrat named John Cummings to do a review of the law. At the time, it didn’t garner any significant public attention.

The final report from Cummings recommended massively increasing the government’s ability to refuse public requests for information. Those recommendations were then drafted into a suite of amendments to the law — Bill 29.

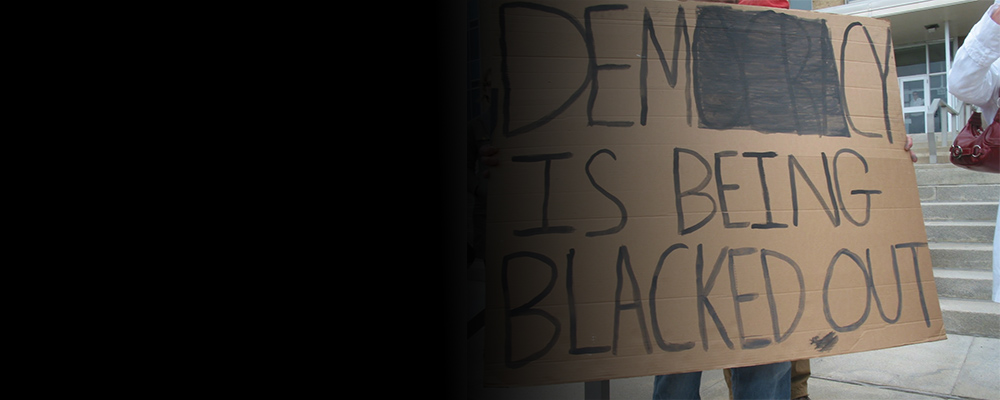

In Newfoundland and Labrador, Bill 29 is a really big deal, which is why it was startling for a lot of people here that CANADALAND did a story on access to information and never mentioned it.

Bill 29 expanded the scope of cabinet confidentiality so that it no longer just covered the deliberations of cabinet, but also any information that might inform the deliberations of cabinet. An embarrassing government report is considered by cabinet? Boom, it’s secret now. Bill 29 allowed the government to ignore any access to information requests deemed to be “frivolous or vexatious.” There are many more examples; suffice it to say, the law was really bad for anybody who wanted to use the access to information system.

When it was introduced into the legislature in 2012, Bill 29 was met with condemnation from the opposition parties, who staged a four-day filibuster. During that debate, Kent — a backbencher at the time — spoke in defence of the policy changes, and actually claimed that the Bill 29 amendments were improving government transparency.

The Halifax-based Centre for Law and Democracy disagreed. They specialize in dealing with access to information laws around the world, and while the filibuster was unfolding, the CBC reported on the Centre doing an analysis of Bill 29. Once enacted, Bill 29 would make N.L. weaker than Mexico, Ethiopia, Nicaragua, Bulgaria, Guatemala and Uganda on access to information.

“The new cabinet exception is, well, breathtaking in its scope,” Centre for Law and Democracy president Toby Mendel told the CBC at the time. “I think it’s one of the widest exceptions of that sort I’ve seen anywhere.”

Bill 29 ultimately passed after the government shut down the debate. Kent voted with the government in favour of the bill.

Political realities

This was a watershed moment in Newfoundland and Labrador politics.

It would be wrong to suggest that Bill 29 was the only factor that dragged the government down, but it was a contributing factor — a big one. For the next couple of years, the opposition parties used Bill 29 as a rallying cry; it fed into a wider narrative of a government that was secretive. “Frivolous and vexatious” became emblematic of the government’s whole attitude towards public criticism.

At the moment, Newfoundland and Labrador is in the midst of an election campaign where the Tories are running more than 40 percentage points behind the opposition Liberals according to multiple polls. The political damage of Bill 29 is one of the reasons for this.

In 2014, in an attempt to undo the damage, the government ordered a review of the ATIPPA law led by Clyde Wells, a former Liberal premier and a retired Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador judge. Wells was joined by retired journalist Doug Letto and former federal privacy commissioner Jennifer Stoddart.

(Full disclosure: As a heavy user of the ATIPPA system, I made a formal presentation at the public hearings held by Wells, Letto and Stoddart.)

After more than a year of study, the final report by the ATIPPA review committee included proposed draft legislation which ran more than 60 pages. That draft legislation was passed by the government essentially without amendment. (There were a couple typos they tidied up, with Wells’ approval.)

It’s true that in the past eight months, Kent has been aggressively enacting the recommendations of the ATIPPA review committee. But any N.L. political observer will tell you that’s mostly a matter of political damage control. The cynics will also say that the Tories are also trying to bind the hands of the incoming Liberal government with a tough new access to information law.

To claim that any of this “can be traced back to Steve Kent’s childhood” is grossly misleading. This was not the story of one heroic minister trying to make things better. This was the story of a government guilty of a massive overreach, and then trying to make it right to save their hides after the public got angry.

A particularly exasperating facet to this story is that Kent himself is currently running for re-election, and he’s down by 17 percentage points to his Liberal opponent, according to one recent poll.

A flattering story about a government minister seeking re-election, devoid of necessary context and misleading readers, feels like the sort of thing that CANADALAND would jump all over, if it was the Globe and Mail or CBC running the story.

As for access to information policy across the country, if there’s a lesson in all of this, I think it’s that people really shouldn’t hope for politicians to come along and make things better, just because it’s the right thing to do. If you want the government to change, it helps to get angry and threaten to throw them out of office.