Canada’s Senate has unanimously adopted a bill that could become the country’s first press-shield law.

Bill S-231, which passed its third and final reading in the Senate on April 11th, would amend the Canada Evidence Act to establish protections for journalists’ sources and make it more difficult for law enforcement agencies to get warrants to spy on journalists.

The bill will now go to the House of Commons for debate. Its author, Conservative senator Claude Carignan — who represents the Mille Isles division of Quebec and until recently was leader of his party’s caucus — is optimistic that it will move forward quickly.

“It seems to have good support from all opposition parties,” he says in an interview with CANADALAND. “If the government has the will to progress the legislation, it could do so quickly.…I’ve started to talk with some [Liberal] MPs. I also raised the question with the justice minister…she seems to be open to study [the bill].”

In the Senate debate, however, Liberal senator George Baker pointed out that the previous bill passed by the upper chamber — concerning drug-impaired driving and also authored by Senator Carignan — had just been “struck down last week” on its first day of debate in the House. He reminded his colleagues that bills not authored by the government can move very slowly and that the Liberals can immediately shut down Senate bills as they enter committee.

“It’s a place of politics,” he said, according to Hansard. “One party wants to remain in power; the other party wants to form power. They are not about to do any favours for members of the opposition.”

Senator Carignan dismissed those concerns. “I don’t expect partisan games on this bill. We have unanimous support at the Senate.…We have the support from the NDP, the Bloc [Québécois], and Conservatives also. I have gotten good reception from Liberal MPs.…When you have the support of the Senate and the media, I think the government has to listen.”

Senator Carignan will be lobbying MPs In the coming weeks and months and says that Conservative MP Gérard Deltell (Louis-Saint-Laurent) will be championing his bill in the House.

On third reading, Quebec Senator André Pratte, the former longtime editor-in-chief of La Presse, summarized the changes that Bill S-231 would make. Per Hansard:

The bill applies to two types of situations. First, when a journalist testifies in a criminal, civil, or administrative court, the Evidence Act is amended to allow the journalist to refuse to disclose a document or information if it would possibly identify a source. The court can only compel the journalist to do so if the document or information cannot be obtained otherwise and if the public interest in the administration of justice outweighs the public interest in maintaining the confidentiality of the source.

The second situation to which Bill S-231 applies is when police forces want to obtain a search warrant, a court order for the collection of information or the authorization to intercept the communications of a journalist, or the collection of documents or information in his or her possession.

According to the jurisprudence, such warrants can only be issued if there are no other means to obtain the information sought or if the public interest in conducting the investigations outweighs the journalist’s right to maintain the confidentiality of the sources. This jurisprudence would be included in the law.

The bill adds additional protections. For example, considering the disastrous experience in Quebec, requests for warrants will be made to superior criminal court judges, not justices of the peace.

One of the main problems with the current process is that the judge only hears the version of the police officers, who obviously have cause to present their case in the most favourable light in order to obtain the warrant they want. Ideally, the judge should also hear [from] the journalist or the media venue concerned, but that is often impossible because they would be informed in advance of the search or tracking.

Witnesses from the media world proposed the idea — which was accepted by the Standing Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs — of offering judges the possibility of using an amicus curiae, a special lawyer who would be responsible for defending the interests of freedom of the press before the court. It would be left to the discretion of the judge whether to request the assistance of such a lawyer or not.

In February 2015, the RCMP went to the courts to obtain a production order for Vice News reporter Ben Makuch’s chat logs with a Canadian-born ISIS fighter. If Bill S-231 had been law at the time, the RCMP would have had a more difficult time getting it. As it stands, Makuch and Vice Media continue to fight that production order and intend to seek leave to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada.

“I think the courts need to have a clear indication from the legislature that the free press is one of our fundamental rights,” says Carignan. “We need to balance the public interest. To reach criminals is part of the balance, but also to protect sources is at the same level.”

Police organizations, according to Senator Pratte’s speech, were concerned that the bill’s original definition of “journalist” was too broad.

So in order to achieve unanimous support, senators amended the bill to define journalists as people whose “main occupation” involves contributing to the media. But, Pratte pointed out, they also added wording to capture those reporting “for consideration” by a publication, so that “freelancers, more and more common in today’s media, remain protected. We’re ensuring that only the sources of professional journalists, career journalists, will be protected by Bill S-231.”

But even if S-231 were passed into law, further legislation would still be needed to give direction to the courts on what rights journalists have when covering unfolding stories. It wouldn’t, for example, protect journalists like Justin Brake, who is facing criminal charges stemming from unlawfully entering a construction site to follow and cover Indigenous land and water defenders.

Section 2(b) of the Charter guarantees freedom of the press. That should be enough, but cases like Makuch’s and Brake’s show that it may not.

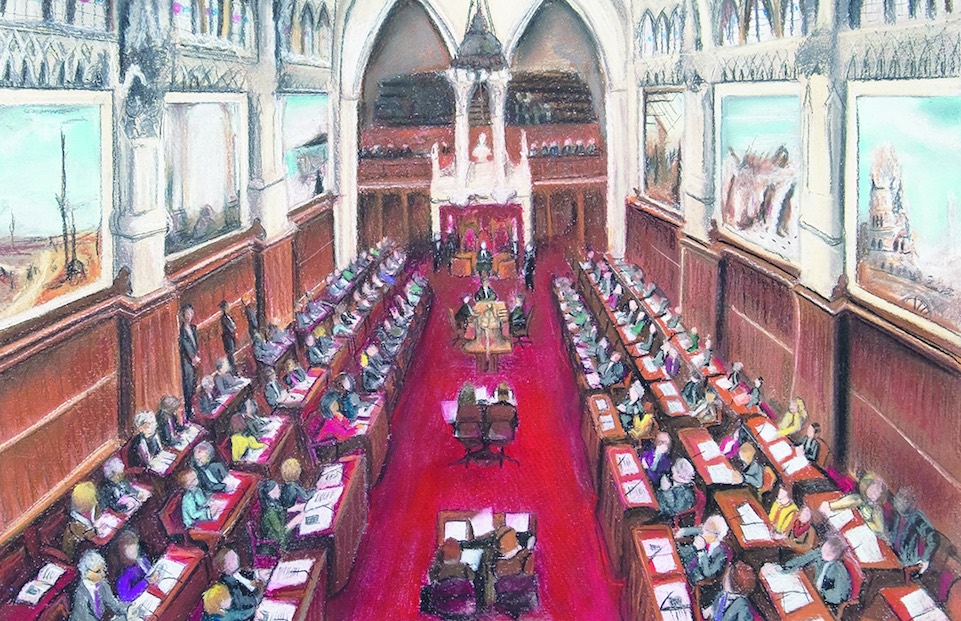

Header image from the Senate’s Perspectives recap-type online thing.