Yesterday, the CBC released its review of Senior Business Correspondent Amanda Lang. It’s awful.

As you may remember, Amanda Lang tried to sabotage her colleague’s investigation of the largest bank in the country, RBC. Working behind-the-scenes within the CBC, she challenged her colleague Kathy Tomlinson’s reporting on RBC as “unfair” to the bank. Then she tried making the story hers, inviting RBC CEO Gord Nixon on to her show for a softball interview in which he shook off responsibility and trashed Tomlinson’s journalism. Then Lang went outside the corporation, penning an editorial for the Globe and Mail (without CBC’s permission) in which she dismissed the scandal her colleague had uncovered as a “sideshow.”

And all of that might have been fine, had she disclosed to her CBC colleagues and to her audience that she had received thousands of dollars in speaking fees from RBC sponsored events and that her partner Geoff Beattie was an RBC board member.

In the wake of CANADALAND’s reporting on these conflicts of interest, the UK Guardian columnist George Monbiot wrote: “It amazes me that [Lang] remains employed by CBC, which has so far done nothing but bluster and berate its critics.”

Lang eventually admitted she should have been more forthcoming about potential conflicts of interest. And CBC News pretty much conceded it had a conflict-of-interest problem when it banned paid speaking engagements for on-air talent.

Despite all of this, yesterday’s review exonerates Lang.

Here are the reasons why it stinks:

1. It makes stuff up.

The review says that “Canadaland suggests that Lang tried to … ‘kill’ the entire story.”

No, we didn’t.

We never used the word “kill” in any of our reporting on Lang. We said she tried to “sabotage” the story. It would have been impossible for her to kill it, as by the time she heard about it it had already been reported.

Why is that an important error? Consider the fact that it’s the same word Lang herself used in her original self-defence, and the word CBC news boss Jennifer McGuire used in her defence of Lang. By exaggerating our coverage and using the same erroneous language, they sought to paint Lang as a victim of nasty trolls.

That a company PR talking point was copied and pasted into a supposedly objective internal review does not inspire much confidence.

The CBC review also says that “Amanda Lang was accused by Canadaland of being in a conflict of interest because of her relationship with a member of RBC’s Board of Directors.”

Nope. Her CBC colleagues accused her of being in conflict, we just listened to them and told their story. The whole reason this story came out was because we were contacted by sources at the CBC who wanted Lang exposed.

And, when we spoke to her, the reporter who broke the RBC temporary foreign worker scandal thought Lang’s behaviour was a problem, too. From our interview with Kathy Tomlinson:

I was very upset because of the perceived conflict of interest [Lang’s various affiliations with RBC] created. Several people then questioned Lang’s involvement in the story – and questioned why she did not reveal any potential conflicts to us up front.

We get it: it’s easier to exonerate Lang from an attack by “the malevolent” (that’s what she calls us) than it is to explain why her own colleagues exposed and denounced her. But that’s what happened.

2. It dodges the point.

The review is designed to exonerate Lang by focusing on her on-air journalism, and not on her conflicts of interest. In an internal email yesterday, McGuire boasted that the review determined “the content of Amanda Lang’s journalism has adhered to CBC’s journalistic standards.”

But the scope of the CBC’s review avoids any explicit ruling on whether Lang’s actions violated conflict of interest rules. The report approaches a judgement several times and then backs off, saying that it’s management’s job to clarify the rules. But the rules are pretty clear: even the appearance of a conflict is a conflict, it’s every CBC employee’s duty to comply with conflict policy, to disclose and remove conflicts and to tell supervisors if they have a possible conflict. Lang obviously violated these.

If the CBC is willing to declare that, according to itself, its journalism is fine, why can’t it take an explicit position on whether or not its conflict of interest rules were violated?

3. It pretends to include an “independent” review.

CBC hired the firm Cormex Research to analyze Lang’s coverage of banks in general to see if her past coverage favoured RBC.

But what does this have to do with the issue at hand? Lang’s coverage of the RBC TFWP scandal is the issue and yet the CBC widened the purview of the only independent party involved in the review so that it could only generally assess Lang’s coverage of all the major banks over a two year period.

Cormex’s findings offer no insight into or assessment of the quality of Lang’s RBC TFWP coverage. That judgment is left entirely to a CBC employee, Director of Journalistic Public Accountability and Engagement Jack Nagler.

So no, you might not find obvious slant towards RBC in two years of coverage. But, if you watch Lang’s interview with Gord Nixon, you will hear him trash the CBC’s journalism as “unfair and misleading,” and you will hear her neglect to ask him “really? How so?”

Nagler, unsurprisingly, doesn’t take issue and suggests that this is a matter of “style,” without giving thought to whether or not Lang’s potential conflicts were a barrier to her ability to adjust her style if, for example, an interview subject attacked the CBC’s journalism on the air.

By the way, since conflicts of interest are the core issue here, we should bring up the fact that Cormex counts RBC, Manulife and Sun Life among its clients. Probably something that should have been disclosed in the review.

4. It actually praises Lang.

The CBC’s review:

“It should be understood that Amanda Lang is probably the only journalist we have who could have secured an interview with Gord Nixon that day. This was a significant ‘get’, and it is due in no small part to the knowledge Lang possesses, the contacts she has, and the sense from Nixon’s side that the interview would be fair.”

This is astonishing. Gord Nixon knew an interview with Lang would be “fair” because his board member was her partner. And that’s among the reasons why she had such great access to him. The CBC basically suggests that conflicts of interest are neat because they give you a leg up on exclusives, nevermind the journalistic ethics.

5. The report’s recommendations kind of admonish Kathy Tomlinson.

The CBC’s review:

“Before going with an investigative story, there should be consultation with any relevant content unit. If it’s about business, that means the Business Unit.”

Oh yeah, that’s absolutely what Tomlinson should have done. Take note, CBC journos: before scandalizing a major Canadian institution, find out if anyone in the building is involved with a board member therein, and run your stuff by them first.

Look, collaboration between units is of course not a bad thing, but what if the unit you’re collaborating with has a member who has conflicts of interest with your story? And what to do when they don’t disclose that to you and instead challenge your story? Knowing that all of this was in play, it’s absurd to suggest that Tomlinson should have let Lang vet her story.

6. It contradicts CBC’s own journalism.

The CBC’s review:

“Lang argued that our coverage was unfair to RBC, which may not have been doing anything wrong… Lang’s critique of the stories is technically correct. Neither RBC nor iGate were shown to have broken the rules.”

This raises a really great meta-question: Does CBC News read CBC News?

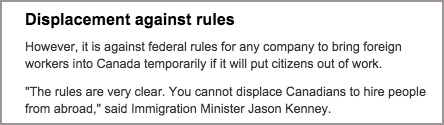

Because, on CBC News’ website, in its RBC TFWP coverage, CBC News says the rules were broken, right above and below the giant, bolded subhead “Displacement Against Rules.”

Jason Kenney, the guy in charge of immigration in Canada at the time, told CBC News, “The rules are very clear. You cannot displace Canadians to hire people from abroad.” RBC was set to lay off Canadians and had its contracter iGate (a company Lang was scheduled to speak for before this broke) bring in hirees from abroad. RBC apologized and the government amended the law to prevent further misuse.

So, let’s add it up: the government thought RBC did something wrong and RBC apologized for doing something wrong. But Lang said they didn’t, and now CBC management says she’s “technically correct.”

7. It covers for Lang’s dalliances with the Globe and Mail.

A few days after the RBC scandal broke, Amanda Lang took to the pages of the Globe and Mail to call the story “a sideshow.” This is a big no-no within the CBC: you need to get management’s permission before writing for a rival news org. Lang didn’t, and the review does in fact ding her for this.

But then she did it again.

When the CBC announced it was banning paid speaking engagements in January, Lang’s quasi mea culpa appeared in the same newspaper as her earlier article. It came in the form of a turgid, lawyerly, 1600-word essay full of nightmarish verb constructs and abominable sentences.

So did she break the rule again to get her own message out? The review doesn’t even bother asking this question, much less answering it.

Here’s another question the review demurs from asking: why did Lang write Globe op-eds anyhow? She has her own show on the CBC, so why break the rules to opine elsewhere?

Neither CBC nor Lang have provided any coherent explanation as to why she went to the Globe in the first place.

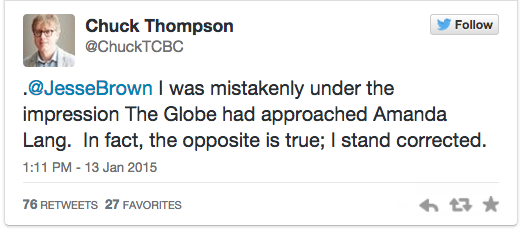

When we first asked the CBC in January about Lang’s original Globe piece, Head of Public Affairs Chuck Thompson told us she wrote it because the Globe and Mail asked her to. After we asked the Globe about it and they denied this, Thompson admitted that what he said was not true and that he was “mistakenly under the impression the Globe had approached Amanda Lang.” We asked Thompson just how he came to be mistaken: where did he get the misinformation from? He didn’t reply.

When Postmedia’s Ishmael Daro asked the CBC if Lang had gotten permission to write this second piece, they wouldn’t answer.

Again, they wouldn’t answer. They wouldn’t answer. This is the biggest problem of all.

This has become the CBC’s MO, in all its scandals and in all its controversies: internal reviews where it gets to make its own judgments about its own behaviour and cherrypick the questions it asks, a circling of the wagons by senior management, a deference to stars, and a refusal to explicitly answer the most pressing and difficult concerns posed to it by the media, by the government and by Canadians.

We did nothing wrong.

But we got caught doing it.

So we are changing the rules.

But we did nothing wrong.

Clearly, the Lang report does not approach the seriousness of another major internal review that’s forthcoming, nor are the events it concerns comparable to what that review will report back on. But the Lang report matters because it’s a test of how seriously the CBC treats the way it’s viewed from the outside, and how honestly it’s willing to look at itself.

In this case, the CBC eliminated the possibility of accountability for the events in question when it limited a third party to a broad analysis of two year’s worth of coverage and left any rulings about Lang’s RBC TFWP coverage to its own employee. It should come as no surprise that this CBC employee exonerated the CBC.

The CBC witheld the right to final judgment of itself to itself, and that is the ultimate conflict of interest.

Editor’s Note: During editing, the outdated phrase “off the reservation” was added to the originally published version of this article to emphasize a point. Whether intentional or not, using this phrase is harmful and offensive. NPR has a good guide for why it is and why it should fall out of use by everyone, including us, here.