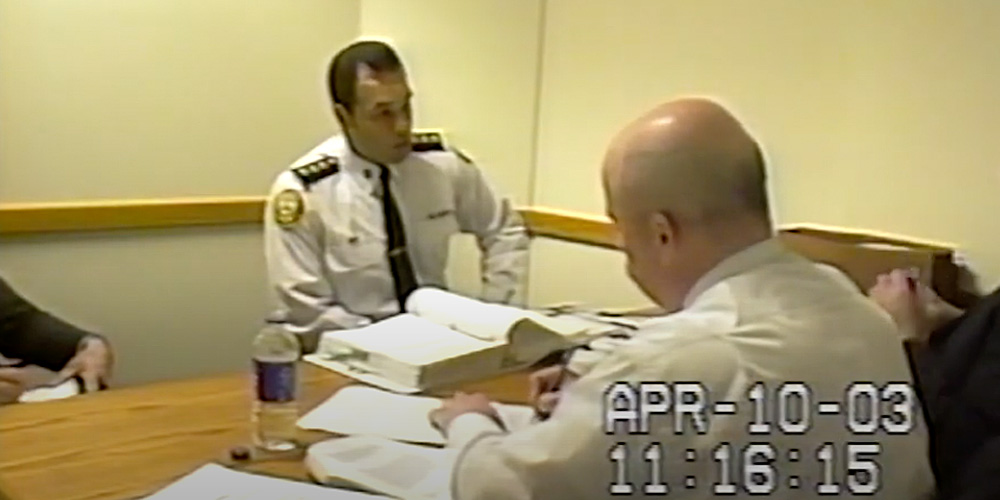

Recently, video evidence of a 2003 internal-affairs investigation of former Ottawa Police Chief Peter Sloly was leaked onto YouTube. In the video, Sloly, then a staff inspector at the Toronto Police Service, is seen defending himself against a complaint regarding his conduct towards a woman he worked with.

“So if people outside the office said they were so concerned about the level of your voice that they debated forcing their way in the door into your office because they were concerned for her safety, they’d be completely exaggerating and misrepresenting the circumstances?” one of the investigating officers asks.

Advising that he can’t speak to how others perceive things, Sloly says, “I don’t know what they were thinking, so how can I say if it’s true or not?” But he denies having yelled.

The Toronto Star reported that the Toronto police are investigating the video’s leak and that no professional misconduct charges were ultimately laid against Sloly under Ontario’s Police Services Act. In 2009, Sloly was appointed as a deputy chief of the Toronto force, a role he held until 2016, when he departed after being passed over for the top job following the retirement of Chief Bill Blair. He became chief of the Ottawa Police in 2019.

While broad concerns about Sloly’s temperament have been reported on previously, the leaked video appears to give the first indication of a specific complaint against him in Toronto. There has been no comment on it from the Toronto Police, Ottawa Police, or Sloly himself.

The video was posted on January 23, the day truckers in British Columbia set out on a convoy towards Ottawa. Questions about Sloly’s handling of those protests led to him stepping down as head of the Ottawa Police Service (OPS) just over three weeks later.

But even prior to the convoy, both the OPS and Sloly’s tenure as its chief had been embroiled in controversy.

In June, Sloly sued Ottawa Life Magazine and its publisher, Dan Donovan, over an article Donovan wrote that pointed the finger at Sloly and the OPS for years of officer misconduct; it was called “Rapes and lies — the cancerous misconduct at the Ottawa Police Service.” Sloly alleges in his lawsuit that, among other things, the article unfairly called him corrupt, incompetent, and stupid, and further defamed him by claiming he allowed harassment and a sexual assault to happen under his watch and that he misused public funds.

While Donovan’s piece contained inflammatory accusations about the behaviour of the chief and the Ottawa police board, it also made a case that a pattern of alleged sexual harassment, abuse, and violent behaviour among officers had persisted for years.

In an interview on this week’s CANADALAND, Donovan lays out why he believes that Ottawa Life — a quarterly lifestyle magazine partly distributed as an insert in the Globe — is the “canary in the coal mine” when it comes to shining a light on problems at the OPS.

“We fell into this completely by accident. I actually had no real interest, [nor] did most of our writers, in writing about the police,” says Donovan, on why he began reporting on the subject. “And then just over a decade ago, there was a horrible case that happened in Ottawa involving a young lady in her mid-twenties.”

In 2008, a 25-year-old Black woman was arrested while walking down a street in Ottawa, accused of public intoxication, taken into police custody, treated to what a judge would later call “two extremely violent knee hits in the back,” and then pinned on the ground by four officers. At one point, an officer cut open her blouse and her bra with scissors. Because that officer was later charged with sexual assault in the case, the woman’s name is covered by a publication ban.

She was left in a cell in soiled clothing for several hours.

The woman later brought a $1.2 million lawsuit against the Ottawa police. The officer who cut off her shirt and bra was acquitted of the criminal charge of sexual assault but found guilty of discreditable conduct under the Police Services Act. He was only docked 20 days’ pay.

In the interview with CANADALAND, as in his writing, Donovans rhymes off a series of Ottawa officers who were charged with misconduct or other offences and subsequently put on paid leave.

In 2021, Eric Post pleaded guilty to five criminal charges of uttering threats and assault relating to four different women, and was sentenced to probation. Post resigned as an officer, and therefore didn’t face a police tribunal. He had been suspended with pay until that point.

In the summer of 2020, Carl Keenan, an Ottawa constable, was found guilty of assault causing bodily harm and given a conditional discharge and two years of probation. If he abides by the conditions of his probation, the charge will be dropped from his criminal record. He was facing nine disciplinary charges from OPS, but he resigned before those could be pursued further. Over the three and a half years he was suspended, Keenan took home in excess of a hundred thousand dollars in OPS salary per year.

Jesse Hewitt was brought up on 10 counts of misconduct by OPS for mockingly filming people with mental-health issues and then circulating the videos among his fellow officers. He was also suspended with pay, until he resigned this past October.

Last week, Deputy Chief Uday Jaswal announced that he would be resigning from the force. He was charged with discreditable conduct under the Police Services Act for allegedly sexually harassing other Ottawa Police employees. Jaswal had been suspended with pay since March 2020. In 2019, a civilian employee with the OPS, Jennifer Van Der Zander, filed a human rights complaint alleging she’d been sexually harassed by Jaswal, who was also her husband’s commanding officer.

While Donovan points to the former police chief for allowing these officers to remain on the OPS payroll, it’s actually provincial legislation that establishes the circumstances under which an officer can be fired.

The Police Services Act also affords chiefs only limited powers to suspend an officer without pay, and in most cases, an officer has to be convicted of a crime and sentenced to a term of imprisonment for that to occur.

How Donovan chose to assign blame for the minimal penalties faced by offending officers forms part of the reasons for Sloly’s defamation claim. (The Ontario Association of Chiefs of Police has long advocated for expanded disciplinary powers, and last summer passed a resolution [pdf] calling on the province to overhaul the police discipline system, so that chiefs would have greater authority to fire or suspend officers without pay.)

Sloly also says Donovan unjustifiably implied that he was corrupt and stupid and not interested in human rights issues outside of race.

Sloly did not respond to CANADALAND’s requests for comment or an interview, but his statement of claim against Ottawa Life offers some insights.

“As a result of his position as Chief of Police of a major Canadian city, Chief Sloly is regularly criticized and critiqued in the media and on social media platforms, on the decisions made by himself and by the Ottawa Police Service,” it says. “However, the article is not an attempt to participate or further public discourse on the issue of policing in the City of Ottawa. To the contrary, it reads as a spell of ranting on various issues, strung together in a manner to increase the defamatory effect on the subjects of the article, including Chief Sloly, and published under the banner of a ‘magazine’ to give it some heightened form of legitimacy and credibility.”

Donovan has accused Sloly of trying to “shut down” Ottawa Life‘s reporting on the police, and likened him to a “bully.” In his filings, Sloly denies that was his intent and objects to being called a bully and “temperamental.” He claims Donovan has in fact acted with malice and that the article stemmed from a “personal vendetta.”

But when it comes to his characterization of the former chief and the force he commanded, Donovan remains defiant.

“Peter Sloly is upset about the way I’m describing this in an article. I think he needs to grow a set and get some sensitivity training,” Donovan says.

“You’re gonna be under the microscope, you account to the public, and if you’re not doing your job, it’s the job of the press to shine a light on it.”