“Out of all the people in the world who have his job,” host Jesse Brown says at the top of today’s CANADALAND, a feature interview with journalist/cartoonist Joe Sacco, “nobody is better at it than him.”

Brown points out, however, that there probably aren’t too many people who do have that job, as author-illustrator-of-full-length-works-of-graphic-nonfiction is something of a niche.

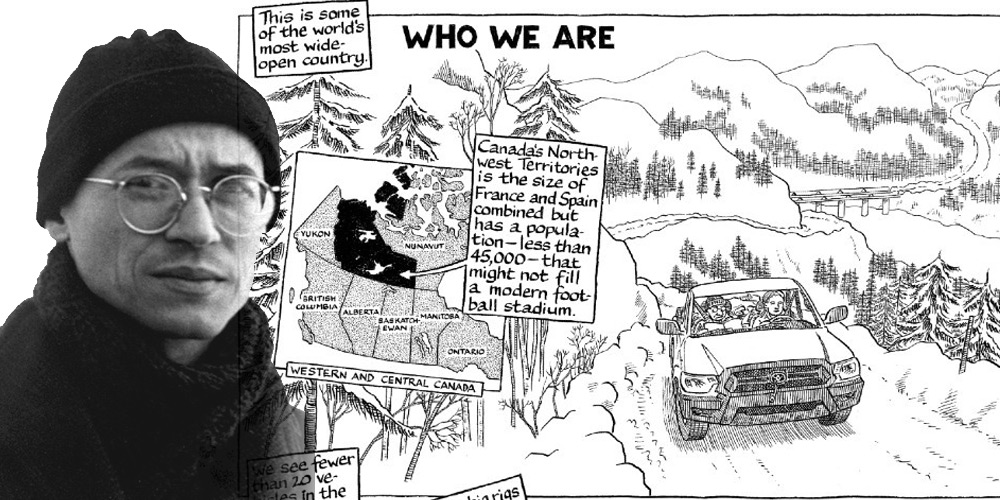

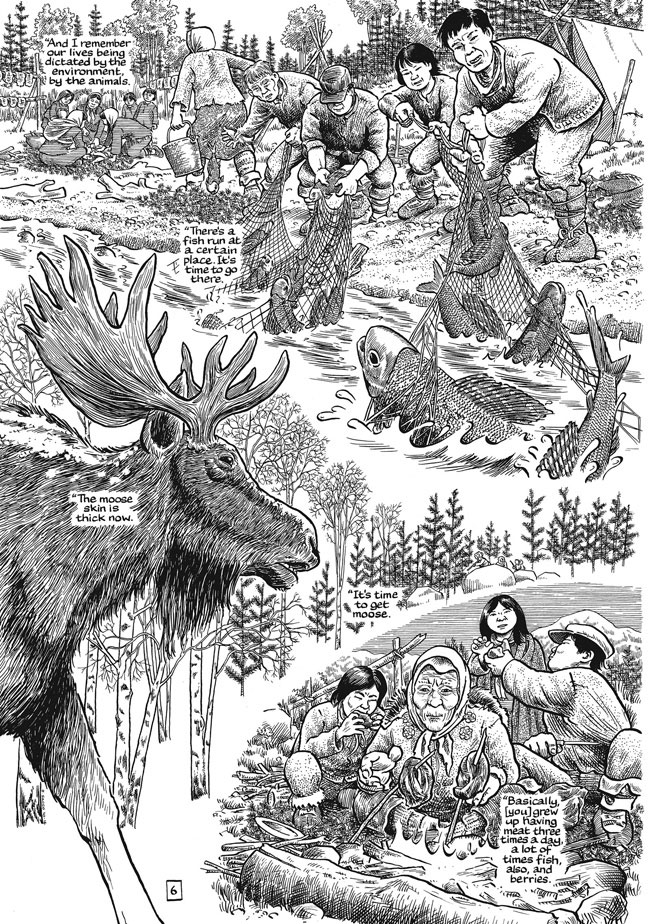

Best known for examinations of conflicts in Palestine and Bosnia, the Portland-based Sacco turned his focus northward in the recent Paying the Land, an exploration of the complicated, colonial underpinnings of resource extraction in Canada’s Northwest Territories and the breadth of responses the Dene have toward it. Brown calls the book “the best journalism about Canada that anybody published last year.”

He spoke to Sacco about the work’s ambitions, the advantages that drawings have over photographs, and how a white person might be able to tell stories about colonialism that function as more than just another extension of it.

The following is a gently edited transcript of their conversation.

Jesse Brown: For people who might be encountering the idea for the first time, how does one do cartoon journalism? You can draw anything — so how do we know that you’re telling the truth?

Joe Sacco: That’s fair. I studied journalism, so I hold myself to a journalistic standard, in particular when it’s in regard to facts, quotes, things like that — I’m trying to be as accurate as possible. But of course, there’s a subjective nature to drawing: you cannot say that a drawing is purely accurate. So there is a little bit of a tension in the work I do, between the facts and quotes, which should be correct, and the drawings, which are my interpretation of some of the things I’m hearing and some of the stories I’m telling. So there’s a fact-based element and a subjective element swirling together in the work I do.

Brown: There are ways in which drawings can be truthful, but I think that may be a difficult concept for some people, especially when “I’m going to draw a cartoon of you” can be construed as “Oh, you’re going to make fun of me.”

Sacco: Yeah, I mean, if you looked at my early journalistic work, it was more wild. There was more of what we in cartooning call the “bigfoot” style, where people were maybe made into caricatures, as far as what they looked like. As time went by, I realized that if this were to have a pretense to journalism, I’d have to draw more representationally. So what I try to do is draw people and things as accurately as I can. It’s either based on photographs or on what I’ve seen myself. It’s not a natural thing for me to try to draw realistically.

Brown: I think it would be reductive to say we’re on a spectrum of cartoony to photorealistic, because if facts lie at the photorealistic end of that spectrum, then why not just have photographs? There’s another way in which a drawing of a person can tell a truth.

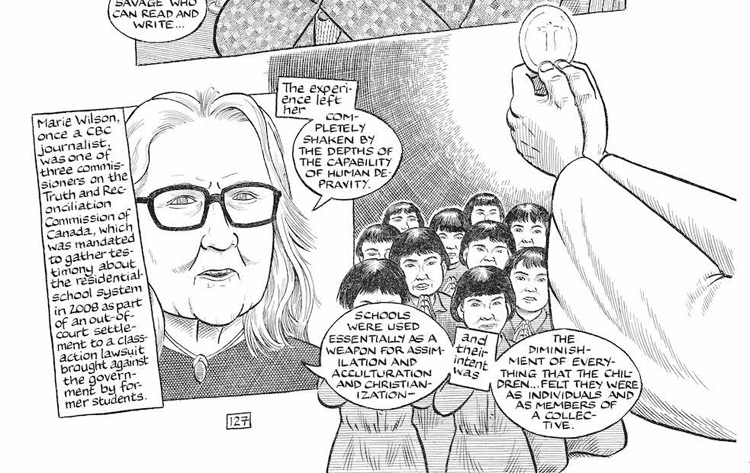

Sacco: Yeah, I mean, it’s about expression, it’s about what you see in a face and what you try to draw out from that face. And it’s also about the sorts of things that drawings can do that photos — as great as photos can be — really cannot do often. They cannot take you into certain places. You know, there aren’t depictions of the violence in residential schools, exactly, in photographs. But that’s something you can recreate in drawings based on what people have told you, based on research you do — photo research in archives of what the buildings and structures looked like, those residential schools. So there’s a lot going on with drawings that you can pull out, that you don’t do so much with photographs. With photographs, you’re trying to tell a whole story with one image — that’s kind of the gold standard for photojournalism. And with comics, you’re trying to build up an atmosphere with repeated images, background information that the reader is taking on into their subconscious, so they get a real feeling for what it’s like to be in a place.

Brown: I’ve been to Yellowknife and to some of the bush in the countryside, and there’s something about photographs or even lived experience. Like, the pictures in my head of being out on a lake there are kind of interchangeable with the ones of me being out on a lake in Ontario’s cottage country. But there’s something that you were able to get at that is more descriptive than what I actually experienced.

Sacco: Well, I tended to think of the land of the Northwest Territories — its very nature as a land — as a character in the book. So I wanted to show how vast it was, the immensity of it and the openness of it. You know, I’m a city guy, so I was quite overwhelmed by it. And I wanted the reader to feel immersed in it. It’s such a big land, and it has such power in and of itself, just the immensity of it.

Brown: The way that we use pictures in journalism is often informational. But then you can also have a kind of more impressionistic, emotional response that one has to a picture.

Sacco: Well, that’s good to hear. The truth is, I was trying to reflect something of what I was getting from the people I was talking to, the Dene people. And they were giving me a sense of their love of the land and the importance of the land to them as people. They’re highly integrated into the land. And I wanted to sort of give a sense of that spiritual connection in my own way. The way I can do it is to draw it in a certain way and reflect something of that reverence.

Brown: Art Spiegelman said, “Because of Photoshop, we all know that photographs lie every second that they open up their mouths. You can’t really trust a photograph. It could have just as easily been a Photoshopped collage. It’s probably more plausible to trust an artist. You get to feel whether you trust them or not.…Artists tend to have to reveal more of themselves, even when they try to be as scrupulous as Joe Sacco.” That made me remember that we can place you in the comics tradition of a Robert Crumb or an Art Spiegelman, but before photographs, drawings used to run with news stories. They wouldn’t have asked somebody to draw something if it didn’t happen, right? Like, that’s how you knew that it happened, if some artist drew a picture of it and it went next to the copy.

Sacco: Well, I mean, there were publications like The Illustrated London News, Harper’s Magazine in the United States, and I’m sure others around the world, where they would send out illustrators with military expeditions, for example. I guess I’m in that tradition, in a way. I have a lot of respect for what photojournalism can accomplish. But you also have to see where is a photograph cropped, what else could they have taken a picture of? I mean, there are many questions around all media. We should all scrutinize ourselves, as far as how close we’re getting to the truth within our particular medium. So whatever subjectivity there is in my drawings, I still want the reader to feel that this is connected to reality.

Brown: The way that you achieve that is not through mere photorealism. There’s a humanity and a dignity with which you draw your subjects that makes them seem very real. But it strikes me as not so much about a dependance on, like, “Does their eye look exactly like that?” or “Is the mole in the right place?” It’s more in the way that I might look at an actor performing a character and ask, “Was that performance real? Did that feel truthful?” There’s a tension there, because of course they’re play-acting, they’re in a costume, they might be wearing a wig. They reach the truth through fabulism. I don’t know if that’s an insult to what you’re trying to do when you get to the truth of how a person talks or feels or presents themselves. But it strikes me as more similar to that than a photograph.

Sacco: That resonates with me, in a sense. George Orwell talks about getting to the essential truth of something, and sometimes someone’s pose, their manner, the way they swivel their head, gives you a real sense of what they might be thinking — body language has a lot to do with it. And I’m trying for those sorts of things. I can’t put my finger on all of it, because there’s a mystery to it, even for myself, and there’s part of me that resists trying to demystify it and actually quantify what I’m doing. What’s important to me is that when the person who’s depicted gets the illustrations, they say, “Yes, this is what it was like.”

Brown: There’s a very honest representation of subjectivity, in that you put yourself in this observer character that a lot of people have come to be familiar with through comics journalism: this, like, hapless witness, kind of Schmendrick character that I associate with a lot of Crumb’s comics journalism. And you’re the only character who’s sort of denied that humanity. Joe, I’ve seen photographs of you: You do, in fact, have pupils, as opposed to how you draw yourself.

Sacco: As I tried to draw more representationally, as I tried to be more journalistic in my approach to the drawings themselves, everything became more realistic except for myself. And that was not a conscious decision. I can draw myself so quickly, it almost became a signature. So a couple years down the road in this process of drawing more realistically, someone said, “How come you still draw yourself that same old way?” And I actually hadn’t even thought about it. I was so used to drawing myself that way, I was kind of the character throughout all my books, that I just, in my hand, I had this signature of what I look like. And it’s been difficult to sort of pull that into the realistic sphere now.

Brown: Yeah, but it doesn’t seem to me that it’s just a function of habit. The simplicity with which you depict yourself gives us a proxy, that we can see these events through this character in a way we wouldn’t if you looked super-detailed or had an individualism that made us wonder, “What’s he thinking? What’s he feeling at this moment?” The focus is on everything else because of how simply you draw yourself.

Sacco: Yes, Scott McCloud, who wrote a book called Understanding Comics and was probably the first cartoonist to really break down what comics do, has said that my character is a little nondescript and that helps the reader put themselves in my shoes. And that might very well be a function of the way I’ve drawn myself.

Brown: It’s in dialogue with other questions that journalists are increasingly asking, about putting themselves in a story in order to own their subjectivity. These dynamics are kind of where we’re at in trying to present the most honest and accurate stories that we can.

Sacco: It was almost accidental, why I appear in my comics. I started out in the autobiographical tradition of cartooning, so when I started doing journalistic comics, I just naturally put my character in there, because that’s what I had been doing. I wanted to demystify the process of getting the story and also, as honestly as possible, to show my relationship to the people I’m with, to show where my sympathies lie, to show what my prejudices are, what has to be sort of taken apart, even in my own thinking — to show the process of learning, basically. And I think all reporters go through that. I expose it, because I think that’s just part of the process. And process to me is really interesting, and I just want to be transparent about it.

Brown: Speaking of the prejudices that you brought to this, my understanding is that this whole project began with your idea of Canada as the North Americans who got it right.

Sacco: Yeah.

Brown: I know you were pursuing a project that was supposed to be about Indigenous peoples and resource extraction all around the world. And you’re like, “Let me start with someplace a little bit safe.” You know, Canada, we’ve got a brand: we’re a gentle, civil place, maybe navigable as a Western society to you. Did that match the truth that you found when you went to the Northwest Territories?

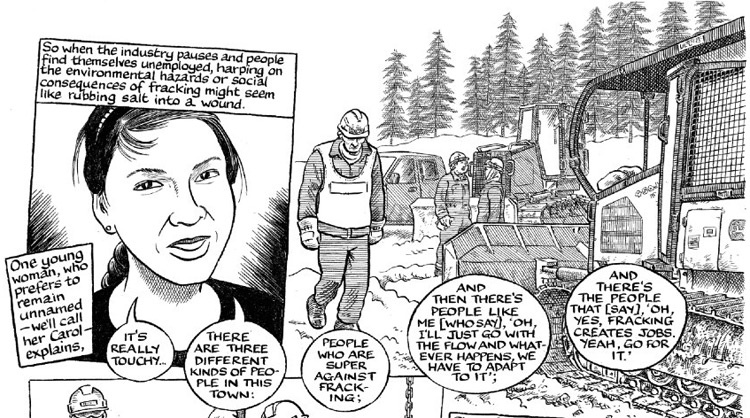

Sacco: No, absolutely not. I mean, I thought it would be a relatively easy story. I was originally doing it for a magazine, so it was going to be a much shorter piece. It was clearly complicated, much more complex than I had bargained for. My prejudice was thinking of Indigenous people as a sort of monolith that all had the same relationship to resource extraction — basically, that they would be against it. And of course you get there and you find out, well, there’s a dialogue. There’s sort of a dialectic going on in the Northwest Territories, between communities and within communities. And I also began to see that you cannot talk about resource extraction without talking about the bigger colonial project that had been going on in Canada. So suddenly I was beginning to get a sense that this was much bigger than I had intended or anticipated. And so I had to come back for a second trip and explore some of those things. It really pulled me in.

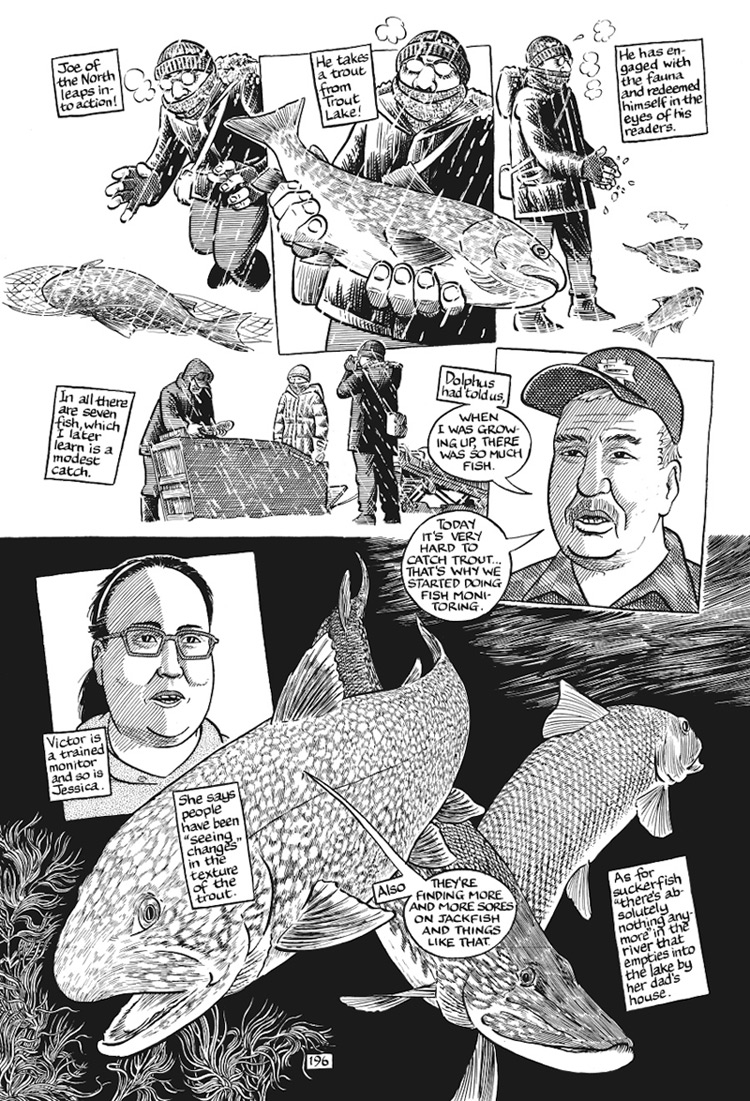

Brown: It’s so natural how one thing leads to another in the book. Like, you can’t talk about fracking and how it’s impacting Dene communities without talking about those communities themselves, their origins, the relationship with the land. You can’t talk about that without talking about economies now, poverty now, alcohol abuse, drug abuse. You can’t talk about those things — it would be irresponsible to — without talking about residential schools. And once you take on the burden of that storytelling, you’ve got to do it right, if you’re going to do it at all.

Sacco: I just had to meet the story where it was. As you say, you have to sort of unravel it and see, what are the consequences of colonialism? What led to the point that we’re at now in Canada? As you mentioned, alcoholism — well, you have to be sort of responsible about it. If you’re talking about alcoholism, you have to talk about residential schools. You have to talk about the whole project of cutting people off from the land, of trying to eradicate their culture, and understand that that’s the connection you have to make. If you’re going to attack someone’s culture, it has its consequences. And so part of the story is putting all that stuff together in the best way I can. And of course, I want to tell all those stories through the eyes of Indigenous people, who were very generous with me, in letting me into what had happened in their lives.

Brown: In the way these things are depicted, you can feel the gravity with which you hold their trust. But it’s still uncomfortable; it shouldn’t be comfortable. It’s difficult to tell stories about what happened to other people when it involves abuse like that.

Sacco: Yeah, it was very difficult. I mean, I’ve had other experiences trying to draw stories that I heard in war zones, and drawing some of those scenes of massacres was always really unpleasant. And I felt the same feeling when I was drawing the scenes that were taking place in the residential schools. I mean, basically a dread of getting up in the morning and going to the drawing table. But also knowing that people have shared their stories with you, and you have to honour what they’ve told you, and sort of get over, you know, your own sensibilities and just approach what they’ve told you as directly as possible, and try to do their stories justice.

Brown: For a moment in the book, you ask the question, “What’s the difference between me and an oil company? We’ve both come here to extract something.” Can you talk a little bit about what you went to the Northwest Territories to extract?

Sacco: I suppose what I went to extract were the stories of people, and the stories of people within the framework of colonialism, and the effects of colonialism, and the unspooling effects of colonialism. That could be a difficult process, because a lot of people there told me, “We have researchers coming here. We have PhD students. We have anthropologists coming here. And they get something from us. We tell them our knowledge. We tell them what life has been like here and about our culture. And then what benefit do we get out of it? People go off and get their degrees and publish their books.”

I have to ask myself, where do I fit in in that equation? And the hope is that the book itself can be returned to the people there and they can see their own stories depicted. And that Canadians can see those stories, the wide range of stories, and maybe take away some of those prejudices that they might have, as I had when I went in. And just learning along with me, basically. I’ve tried as much as possible to be careful with the stories and present them in a way that’s as respectful as possible, because, along the road of doing this story, I was reminded by people, “You’re a white guy going in there doing this stuff.” These days, we’re much more cognizant of where someone comes from when they’re telling someone else’s story. And I do come from the West. But part of the gift that I got from doing this story was it helped me examine my own beliefs, my own prejudices, my own Western nature. And, you know, an anthropology of one people is, on some level, an anthropology of the anthropologist. I want to show there was sort of a reciprocal relationship: that if I took something, I gave something back.

Brown: That’s interesting. That moment came about when somebody asks you for money in exchange for their story and you kind of scoff at that because it’s against our rules. But there’s another moment later on, where a Dene woman is trying to learn from an elder how to tan a moose hide, and she’s writing down the instructions, and the elder says, “What are you doing? Just do it.” These are different traditions. These are different ways of learning things, different ways of seeing things and doing things.

Sacco: Right, I mean, the way she put it to me was that she had to decolonize herself. She had to stop thinking in terms of the way Westerners think of things, and think of things in terms of how a Dene person thinks of things. And so the process of decolonization is a concept that I came across there: people thinking about who they are and trying to not think of themselves through the eyes of someone else, of the Westerner.

It’s not just the colonized that have to decolonize themselves — it’s the colonizers, in a way, that have to decolonize themselves. And on some level, I would have to think of myself as part of the colonial project. And what this book helped me do was become aware of the fact of myself in the colonial project — in my case, as a recent immigrant to the United States, basically living off the fruits of colonialism. So this book helped me think in those terms and helped me decolonize myself on some level. I mean, I’m sure there’s a long way to go. But that was another gift I felt I got from this whole project.

Brown: You’ve said that how your subjects feel about their portrayal matters more to you than even good reviews of the book. That’s not something journalists are supposed to say; we’re supposed to care about accuracy, and if your subject doesn’t like how they’re portrayed — which happens all the time — you know, tough shit. Does that fall under this decolonization of your practice as a journalist, to question some of those concepts about how we tell stories?

Sacco: I think pretty much in all my work, I realize that I’m usually visiting a place for what can be a relatively short time. I mean, I was only in the Northwest Territories for about six weeks in total over two trips. So it’s always been about what the people I’ve made those connections with think of the book. How do they think about how they were portrayed? And I’ve portrayed people in ways that were unflattering that they still thought were fair. So it is possible to do that. As long as they can recognize themselves and not feel it’s a caricature, then I’m getting closer to something that I can be proud of.

In this case, the stuff that I was most worried about was going back into the past. And I did my photo research, I did a lot of research, and I sent the pages to one of the people in question, Paul Andrew. And he was happy about it. He felt that it worked. You know, I’m sure he could have quibbled about certain things, but I think in the end he felt it was a very useful project for helping younger people understand what he went through. And if he was satisfied with it, then that is where I was content.

You have to trouble yourself with thinking about how the people you’re depicting are going to relate to the material. I don’t think of those people as people you extract from and leave behind. In the end, there has to be sort of a remediation, some attempt to make it as painless as possible, and to present something that they think, “Okay, this was worth our time.”

We got the Book "Paying the Land" it's about us in graphic novel done by Joe Sacco pic.twitter.com/1094yrk2dK

— Jim Antoine (@northdegaa) July 15, 2020

Brown: One thing that diverges from the way these stories are usually told is the lack of conflict, in a certain way. If somebody is going to drop in to do a story about resource extraction, I would expect them to go to the tar sands or, these days, Wet’suwet’en. You went somewhere where, the price of oil is so low, the fracking that you’re documenting isn’t really even taking place. These were not depictions of protests stopping pipelines. You really document the nuance with which different communities are taking different positions as to whether resource extraction should take place, and if so, on what terms. In the nature of the story you’re telling, the typical journalistic question of going to the CEO of an oil company for comment didn’t feel like a journalistic necessity.

Sacco: No, it didn’t feel like it to me, because that’s the dominant narrative you’re going to get, from government and from business. And I was much more interested in the different, and often conflicting, opinions I found within the Indigenous communities, so I was much more focused on that.

Brown: It is as much an exploration of your education, of trying to come to terms with a very different way of thinking. And it feels to me like the book climaxes with your depiction of a young Dene man who, on a hunt, has this amazing moment of spiritual connection with his ancestors, with future generations, with the land, thinking about the feet that stepped where he is. You’re trying to illustrate something that he was generously conveying to you, but it’s almost like I could feel you — like something clicking for you in that moment and then clicking for me as the reader that maybe I’d never really understood before. Not just a different form of spirituality, but a different way of situating oneself.

You know, I can read on the back of the book a nice sentence like,”The Dene don’t feel like they own land. They feel like the land owns them.” And that seems like a nice, concise summary of something. But it takes the whole book for that to really make sense to me. And just talking to you now, it feels like that’s as much about you coming to understand that as you telling the story of that happening to someone else.

Sacco: Well, I think you depict only what you can begin to understand, and maybe if I didn’t understand, I would never have depicted that. But to see Indigenous people — and someone like him, Eugene Boulanger — talking about the past and the future and the connection between those things, that to me is in quite contrast to how we think in the West. This generation now, we can barely think of what our children are going to inherit.

I didn’t want to be so explicit about the ecological lessons in the book, but just the fact that someone will think of the past and the future as a continuum, and the responsibility to it, is a pretty simple and powerful message. And that spiritual connection, which, we simply don’t have those or talk in those terms in the West.

Brown: Through narrative, you take us to this place where that mentality and that worldview feels incredibly current and incredibly important, as you’re illustrating, you know, a way of containing arsenic underground that has only a 100-year safety guarantee. As we’re all facing very imminent and present consequences for how we’ve extracted from the land, that philosophy feels like something that’s burning with urgency.

Sacco: That’s our version of paying the land; there is no spiritual component. And I agree, I mean, I’m not a religious guy. But it’s a bit humbling to be around people who, at their best, I think, live a spirituality. We would be right in the West to sort of think about that a little.

Sacco portrait at top by Michael Tierney, alongside an excerpt from Paying the Land.