The Wet’suwet’en crisis in BC has dominated the news for the last week. It began with an RCMP crackdown on supporters of a group of Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs, who oppose the construction of the Coastal GasLink liquefied natural gas pipeline through their territories. The builder of the pipeline, TC Energy (formerly TransCanada Corporation), asserts that they have the right to build it, having first obtained the support of five of the six Wet’suwet’en First Nations. The sixth declined to offer their support as they, in agreement with the hereditary chiefs, state that as an Indian Act band council, they do not have authority off reserve, and that only the hereditary chiefs can determine what happens to unceded, non-reserve lands like those through which TC Energy seeks to build.

Since the crisis began, dozens of explainers have appeared in the press that try to get to the root causes, and which seem to grant legitimacy to one side or the other. Each such piece speaks with authority and certainty over the facts at play.

However, those facts are often contradictory.

In a February 12th opinion piece, the Vancouver Province’s Mike Smyth wrote that “protesters have aligned themselves with five Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs opposed to the pipeline.”

However, the day before, The Globe and Mail’s Wendy Stueck reported, “Now, nine of 13 hereditary house chief positions are filled by men. Four of the positions are vacant. Eight of the nine men have said they oppose Coastal GasLink. One of the house chiefs has taken a neutral position.”

In their press materials, the supporters of Coastal GasLink point to a Wet’suwet’en hereditary chief named Theresa Tait-Day, who supports the pipeline. (Tait-Day’s status as a hereditary chief is disputed, something which doesn’t appear in reports touting her support.)

The Office of the Wet’suwet’en — the official organization representing the hereditary chiefs — lists just seven chiefs, not five, nine or 13, and does not include Tait-Day.

The number of senators in Canada is not a matter of opinion. The number of MLAs in the BC legislature is known, as are the number of town councillors in Pouce Coupe, BC, and Meaford, Ontario (87, four, five, respectively). The number of Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs, and the number who stand in opposition to the pipeline, should not be uncertain at the height of a national crisis, and in the third year of this dispute breaking into the headlines.

According to the survey, 40% of First Nations say they haven’t been visited by a reporter in the last five years and 8% say they have never been visited by a member of the media.

While the rail system is shut down coast to coast, we don’t know how many chiefs are opposed to the pipeline, we don’t know for certain what percentage of people in the Wet’suwet’en country support or oppose the pipeline, and we don’t know if the pipeline was approved by a referendum, a town hall, or a simple vote in council. With that information gap, people grasp onto whatever numbers are presented to them. Over the weekend, Jason Kenney tweeted out a Canada Action post saying that 85% of the Wet’suwet’en support the pipeline. A search online turns up no poll or survey behind this number. The First Nations LNG Alliance Twitter feed suggests that the number may be 80%. And again, this number is difficult to verify. LNG Alliance board member Chief Dan George has been using it in media appearances, describing it as the result of a “community vote.” But details of such a plebiscite are hard to come by.

A message to reporters and news media from @NationalChiefs: If 80% of Wet’suwet’en people support the #CoastalGasLink pipeline, shouldn’t 80% of your interviews be with pipeline supporters? pic.twitter.com/FXupkd39uS

— FN LNG Alliance (@FNLNGAlliance) February 12, 2020

The uncertainty over any of these facts exposes a major failing in the reporting of this story — the absence of reporting from on the ground inside Wet’suwet’en territory. And it’s a failing by the media that has arguably made this crisis worse.

Absent facts, both sides — those supporting the chiefs and those supporting the band councils — rely on information fed to them by advocacy organizations. On the chiefs’ side, information comes from collections of activists, most prominent among them the social media feeds of the Gidimt’en Checkpoint and the website of the Unist’ot’en Camp. On the council side, information is pulled from industry-aligned groups like Canada Action — makers of the ubiquitous “I [heart] [maple leaf] Oil & Gas” t-shirts.

Last week, as the press was reporting from blockades and protests across Canada, two events were held in the Witset First Nation — the largest of the Wet’suwet’en First Nations, home to a third of the total population. The Witset had a band council meeting on Wednesday and an All Clans gathering on Thursday. As you can imagine at the height of such a crisis, these should naturally be overwhelmed with reporters trying to get the pulse of the community at the centre.

However, a search of Google News shows no reporting from either. On social media, there is some discussion that the All Clans event took place, but no details of how it went, and no coverage at all of the band council meeting that I can find.

In spite of this information gap, people speak with such certainty on this issue. Both sides claim to be arguing for the community, but other than a handpicked few who are put forward by Canada Action and the supporters of the hereditary chiefs, the community is largely silent.

This problem isn’t unique to the Wet’suwet’en crisis. There is a shocking gap in coverage of First Nations communities across Canada. Wawmeesh Hamilton covered this gap in a 2016 series for The Discourse. He interviewed the CBC’s Duncan McCue, and asked him why coverage of First Nations communities was so limited:

First Nations stories are out of sight and out of mind — and not just geographically. “It’s a nuanced difficulty, but it often comes down to whether or not non-Indigenous senior editors even care enough about Indigenous issues to put them in their news lineups,” he says.

Over the last year, as part of my research for an upcoming article for The Walrus, I’ve been looking into coverage of First Nations and related issues of press freedom on reserve. Last fall I reached out to more than 500 First Nations band offices across the country to conduct a survey. In addition to my main subject, I took the opportunity to poll band administrations on their experiences with the media.

Those that replied painted a portrait of journalistic neglect. According to the poll, 40% of First Nations say they have not been visited by a reporter in the last five years and 8% say they have never been visited by a member of the media.

This reporting gap isn’t something that is entirely the fault of reporters, though.

The majority of bands I surveyed (56%) require reporters to seek permission to visit reserve, and nearly a third (32%) have denied reporters permission to enter reserve. That being said, when asked “Do you believe that Canadian media have the right to cover issues on your reserve?” 84% of those who responded said “yes.”

This crisis began with journalists being denied access to Wet’suwet’en land defenders by the RCMP. As it continued, journalists complained about being denied access to the BC legislative assembly by anti-pipeline protesters.

I can find no record of a journalist complaining about being denied access to a Wet’suwet’en reserve.

Instead there are numerous headlines about the theoretical effects of the rail blockades set up by supporters of the hereditary chiefs.

On February 16th, the CBC reported, “Rail blockades to lead to shortages of propane and consumer goods, 2 national groups say.” Earlier last week, the Financial Post declared a “Potential catastrophe,” writing that “Rail blockades disrupt supply chains for food — which may lead to grocery shortages.” Global gave Indian Country the schadenfreude-inducing headline “Concerns raised about drinking water as chlorine delivered by rail held up by blockades.”

Writing doomsday headlines is likely more fun than the half-hour drive to reserve from the airport in Smithers, BC. But the latter is what Canada needs — real reporting from on the ground, on reserve in Northern British Columbia.

The number of chiefs in support of the pipeline, the level of community support, the reaction to these events by regular Wet’suwet’en people — these are all facts that could be ascertained and which would undoubtedly influence public opinion, and could even have an effect on the outcome of the current crisis.

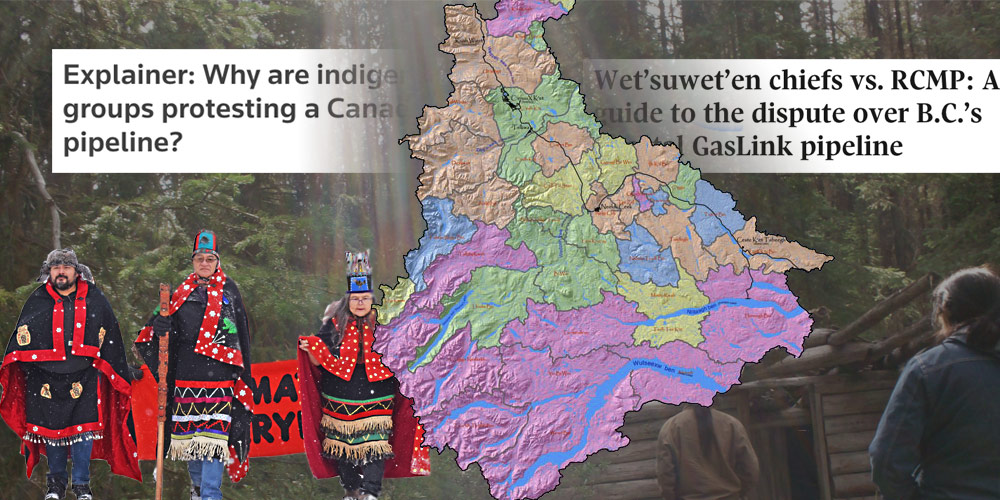

Top collage incorporates headlines from Reuters and The Globe and Mail, as well as a map and photo from the Office of the Wet’suwet’en, as well as a photo originally from The Interior News, via the Unist’ot’en Camp.