Eric M. Adams (University of Alberta), Jordan Stanger-Ross (University of Victoria), Nicholas Blomley (Simon Fraser University), and Vivian Wakabayashi Rygnestad are members of Landscapes of Injustice, a project investigating the history of the dispossession of Japanese Canadians.

The adage that those who forget their history are doomed to repeat it came alarmingly to mind recently, when Vancouver’s two largest daily newspapers revived a series of dangerous racist tropes sadly once familiar in Canadian media: that some groups of immigrants could not and would not assimilate, that a disturbing vision of a white Canada was under threat from outsiders, and that racialized people constituted an “enemy within.”

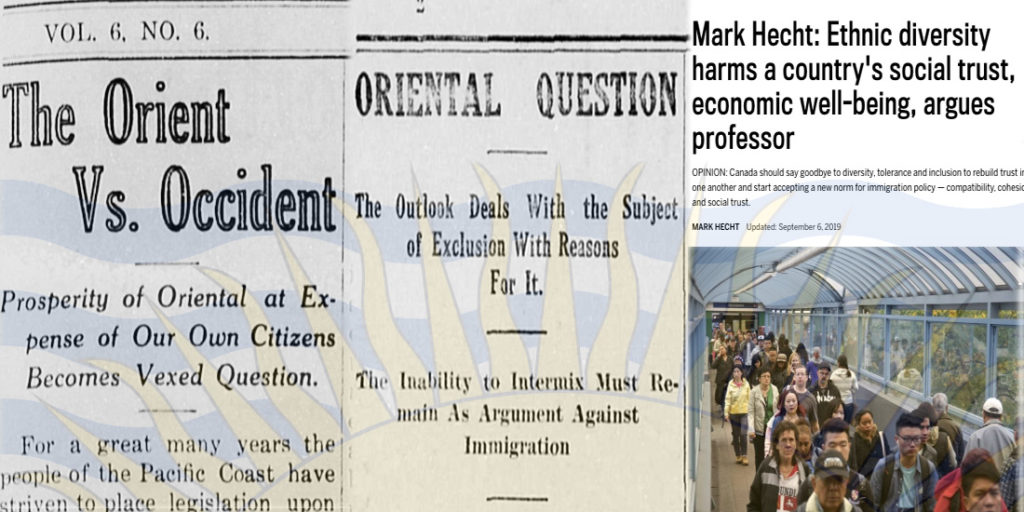

In early September, the Vancouver Sun and Province published an op-ed by Mark Hecht denouncing “diversity, tolerance, and inclusion” in favour of the alleged economic and social benefits of a homogenous society of whites, preferably Protestants. The author complained of “arrogant” immigrants “with no intention of letting go their previous cultures, animosities, preferences, and pretensions” below a photo of Vancouver residents living their everyday lives, taking public transit to commute to work or school. Both newspapers pulled the piece from their websites and apologized to readers, although not before the Sun distributed roughly one hundred thousand copies of the editorial as part of its weekend print edition. (The author, a Calgary-based geography instructor, has now been invited by a University of British Columbia “freedom of expression” group to speak on “Academic Freedom to Discuss the Impact of Immigrant Diversity.”)

Expressing regret in such circumstances is not enough. We have seen this before in British Columbia, and we ignore that history at our peril.

Racism arrived in British Columbia with settlers claiming sovereignty over the territories and governments of Indigenous Nations starting in the 18th and 19th centuries. Newcomers themselves, white settlers employed arguments about white supremacy to distinguish themselves from others arriving in the province. Theories constructed about racial supremacy went on to support the Indian Act, the banning of the Potlatch, the abandonment of treaty promises, the refusal to recognize Indigenous Nationhood, and the creation of residential schools. By the 1930s, editors of the Vancouver Daily Province, confidently told readers that Vancouver was “no place for the primitive wards of the government.”

But not all settlers were welcomed. In 1900, a Royal Commission was called to investigate Asian migration in response to the government of British Columbia’s allegation that “the province is flooded with an undesirable class of people non-assimilative and most detrimental to the wage-earning classes of the people.” Disturbingly similar to Hecht’s column, witnesses told the Commission that Asian migrants could not properly understand or follow Canadian law, harmed the economy, and endangered social cohesion. In the words of British Columbia’s submission: “the average Japanese remains what he always was, a Japanese, and [even if he is a Canadian citizen] he never becomes, in truth and in fact, a Canadian, but always remains a Japanese.”

Racist rhetoric of difference, inferiority, and the enemy within, supported by the political establishment and repeated by newspapers, was used to justify restrictions on immigration, voting, and employment. On July 25, 1907, the Province warned its readers that an ocean liner “literally swarmed with little brown men” had arrived to the harbour from Japan. That September, thousands of white residents marched through Vancouver’s streets promising to “stand for a White Canada” by smashing the windows of the businesses and homes of Canadians of Asian descent. In 1925, the Vancouver Sun applauded a federal act excluding Chinese immigrants from Canada, on the grounds that immigrants from China could not assimilate.

Within a public culture that characterized some groups as fundamentally less Canadian, extreme forms of injustice became possible. During the Second World War, federal laws requiring registration cards for all persons of “the Japanese race” were followed by the mass internment and incarceration of Canadians of Japanese origin. After uprooting Japanese Canadians from their homes, businesses, and communities, the government issued orders seizing all real and personal property of Japanese Canadians, with a promise to protect and return it. In January 1943, the government instead broke that promise and ordered that all seized property — every home and personal possession — be sold. When the war ended, and internment continued, the government of Canada devised a new plan, exiling as many Canadians of Japanese origin as possible to Japan. All of this was easier to do to a group of people who supposedly did not belong in the first place.

Throughout it all, editorials in the press applauded.

“The gallant fight of the … Vancouver Sun to remove the Japanese Old Man of The Sea from the shoulders of [British Columbia] has been crowned with success,” the newspaper announced in 1944. The government’s exile policy, editors wrote, “practically meets the campaign which The Sun has waged for a long time that British Columbia should be preserved as a white province.”

This history and the enduring legacies it carves into British Columbia is why a tardy retraction and brief apology fell short. We have travelled these roads before to devastating consequence. Awareness and retelling of the harms of British Columbia’s history of race and belonging, and recognizing the media’s role in that past, is a first step in combatting the racist myths that tragically still get delivered to our doorsteps.

Top image features clips from the Prince George Herald (October 16, 1915), the Prince Rupert Journal (January 31, 1911), and the Vancouver Sun website (September 6, 2019). Historical newspapers via the University of British Columbia’s digitized collection.

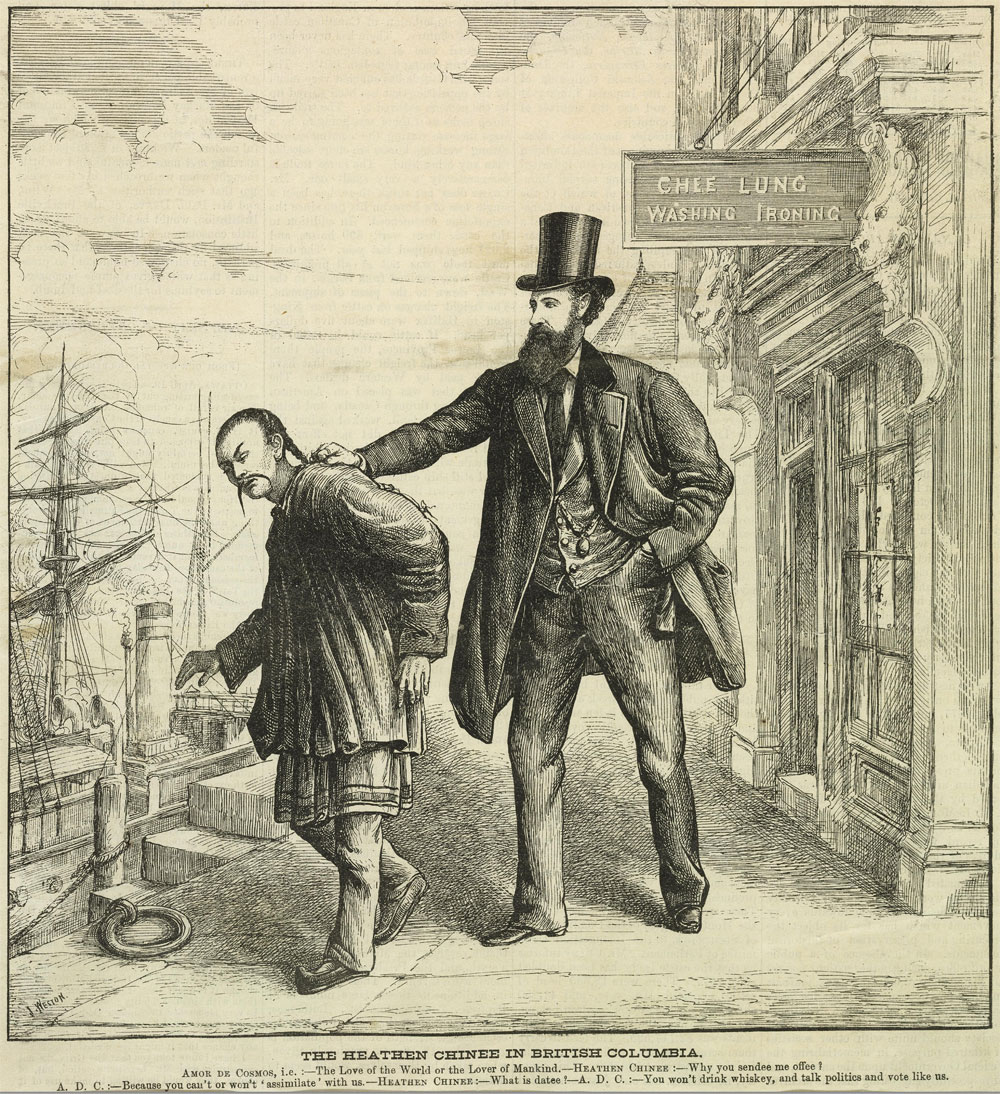

Clarification (October 2, 2019, at 4:49 p.m. EDT): An image caption has been revised to clarify that the figure depicted in a political cartoon was BC politician Amor de Cosmos and not just a generic white man.